A Memphis Story

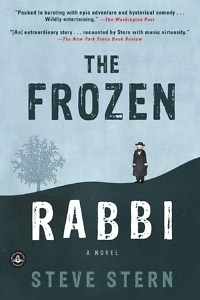

Steve Stern’s The Frozen Rabbi is an absurd, exuberant, razor-sharp family saga

When I started teaching at the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga, I held class in the Fellowship of Southern Writers Room in the Lupton Library. An unconventional classroom, the walls were hung with gorgeous black-and-white portraits (by photographer Curt Richter) of members of the fellowship, a group established in 1987 whose charter members include Walker Percy, Robert Penn Warren, and William Styron. I may have been teaching required freshman comp, but I was surrounded by giants of my literary imagination. These were my people. These were my stories.

Though I felt at home in the language and settings of Southern literature, I wrestled with the question of how Southern literature has been defined over the years. Though the fellowship itself was founded by a group that included Louis D. Rubin, Jr., Ernest Gaines, and others outside the racial and religious majority, Southern literature as a body has tended toward a depiction of the South that is largely rural, white, and Christian. Besides the rural component, these issues transcend the region and have been a problem across publishing for decades. But when I look at the figures who have risen to the highest prominence – Faulkner, Welty, O’Connor – I still wonder about the South they depict and why I found it so comforting.

Though I felt at home in the language and settings of Southern literature, I wrestled with the question of how Southern literature has been defined over the years. Though the fellowship itself was founded by a group that included Louis D. Rubin, Jr., Ernest Gaines, and others outside the racial and religious majority, Southern literature as a body has tended toward a depiction of the South that is largely rural, white, and Christian. Besides the rural component, these issues transcend the region and have been a problem across publishing for decades. But when I look at the figures who have risen to the highest prominence – Faulkner, Welty, O’Connor – I still wonder about the South they depict and why I found it so comforting.

Certainly some of the people and places I find in those stories remind me of my extended family in Middle Tennessee, but I grew up in the suburbs of Chattanooga, a midsized city with little in common with Yoknapatawpha County. I went to a diverse downtown school and had friends who demonstrated their faith through classical Indian dance, friends who listened to more rap than country, and friends whose bat mitzvahs were the highlight of the year.

Perhaps, then, it should come as no surprise that my appreciation for Southern lit has always been accompanied by a healthy dose of questions about which books and authors were readily included under that umbrella: Where were the BIPOC writers, the Latinx born abroad and now living in the South? Why aren’t those who write for young readers included, and where were those creating stories about Southerners who worship at a synagogue or mosque? Where were Angie Thomas and Saeed Jones and Kiese Laymon and Brandon Taylor? Where was Nikki Giovanni or Jericho Brown or Carmen Agra Deedy or Aisha Saeed? And most recently, I would add: Where was Steve Stern?

My introduction to Stern came through a Chapter 16 assignment to review his latest: The Village Idiot. It’s a remarkable book, and I was blown away. So when I had the chance to return to Stern’s unparalleled wordsmithing, I jumped at the chance. I secured a copy of The Frozen Rabbi and was immediately intrigued, despite treading on unfamiliar ground. Stern grew up in Memphis, and in an essay for Chapter 16, he describes the religion of his upbringing as “the Reform Jewish ‘tradition,’ though the word here is gross hyperbole.” He goes on to explain, “The temple I attended as a kid in Memphis represented a variety of Judaism designed to be invisible, to blend indistinguishably with the Christ-haunted Southern landscape.” Nevertheless, Stern’s books are unabashedly Jewish, filled with Yiddish phrases and cultural references that do not make me feel at home. Instead, they add words to my vocabulary and remind me of all that I do not know. They dazzle and delight me. They stretch me and impress me and make me laugh. God, do they make me laugh.

My introduction to Stern came through a Chapter 16 assignment to review his latest: The Village Idiot. It’s a remarkable book, and I was blown away. So when I had the chance to return to Stern’s unparalleled wordsmithing, I jumped at the chance. I secured a copy of The Frozen Rabbi and was immediately intrigued, despite treading on unfamiliar ground. Stern grew up in Memphis, and in an essay for Chapter 16, he describes the religion of his upbringing as “the Reform Jewish ‘tradition,’ though the word here is gross hyperbole.” He goes on to explain, “The temple I attended as a kid in Memphis represented a variety of Judaism designed to be invisible, to blend indistinguishably with the Christ-haunted Southern landscape.” Nevertheless, Stern’s books are unabashedly Jewish, filled with Yiddish phrases and cultural references that do not make me feel at home. Instead, they add words to my vocabulary and remind me of all that I do not know. They dazzle and delight me. They stretch me and impress me and make me laugh. God, do they make me laugh.

The Frozen Rabbi begins in the book’s present day (1999) with the following: “Sometime during his restless fifteenth year, Bernie Karp discovered in his parents’ food freezer — a white-enameled Kelvinator humming in its corner of the basement rumpus room — an old man frozen in a block of ice.” Don’t be alarmed. This is not the start of a murder mystery or the story of how Bernie discovered his father is a serial killer. No, this frozen figure is an heirloom, as Bernie’s father explains: “Some people got taxidermied pets in the attic, we got a frozen rabbi in the basement. It’s a family tradition.”

Better yet, the rabbi isn’t even dead — a fact we discover along with young Bernie when the power goes out during an electrical storm and the rabbi thaws. Awakened from 100 years of meditation on ice, the rabbi quickly discovers a world of modern conveniences and banal entertainment before becoming a wildly popular New Age spiritual leader. If this all sounds ridiculous, that’s because it is, but Stern is unbelievably good at making readers embrace the absurd while also supplying uncommon insight and an abundance of humane intelligence.

The Frozen Rabbi is a comical and razor-sharp commentary on modern capitalism and the marketing of mystical self-help opportunities; it also traces decades of Jewish migration, from Poland to New York to Palestine to a Jewish neighborhood in Memphis known as the Pinch. As the ice block of rabbinical wisdom gets passed from generation to generation, it follows the path of countless immigrants who know what it means to stand outside a story, excluded from the language and the practices, never inside enough to get the jokes.

Stern’s novel is full of outsiders. In addition to the icebound rabbi himself, there is Max, who was Jocheved back home and adopted a male persona after being raped and losing both her parents. On the journey to America, Max “thought about his bedfellows in third class and wondered what, aside from their shared rootlessness, they had to do with him.” There’s also Lou, Bernie’s girlfriend, though “in her case outcast was something she seemed to have elected to be.” Of Shprintze, one of the refugees at the Holy Land settlement, we learn that “while the others began in time to be assimilated into the life of the colony, Shprintze … remained aloof.” She alone spoke only Yiddish, refusing to use “the sacred tongue.”

Stern’s novel is full of outsiders. In addition to the icebound rabbi himself, there is Max, who was Jocheved back home and adopted a male persona after being raped and losing both her parents. On the journey to America, Max “thought about his bedfellows in third class and wondered what, aside from their shared rootlessness, they had to do with him.” There’s also Lou, Bernie’s girlfriend, though “in her case outcast was something she seemed to have elected to be.” Of Shprintze, one of the refugees at the Holy Land settlement, we learn that “while the others began in time to be assimilated into the life of the colony, Shprintze … remained aloof.” She alone spoke only Yiddish, refusing to use “the sacred tongue.”

The people of the Jewish diaspora exist in exile, but by maintaining ties to their cultural heritage and religious traditions, they remain connected. Max/Jocheved and Shmerl (Bernie’s great-grandparents) are isolated upon their arrival to the United States, but once they meet, everything changes: “Outsiders for so long, together they felt what neither had before.” For Shmerl, “It was as if he finally belonged to the teeming neighborhood and had at last arrived in America.”

As the years pass, the assimilation progresses until we reach Bernie’s father, Mr. Karp, who is “a joiner, an affiliate of local chapters of the Masons, the Lions, and the Elks, his enrollment dating from a time when Jews were not always welcome in such organizations. His prominence and civic-mindedness, however, had earned him the status of honorary gentile.” No longer isolated in the Pinch, Julius Karp moves to the suburbs, convinced that “he had no relation to the so-called Jewish homeland; his own place was here in the South.” Memphis may not have welcomed him, but he has made his way, though – it must be asked – at what cost?

Because he can’t read Yiddish, Mr. Karp doesn’t know his family’s history (recorded in his father’s journal), but thanks to his experiences with the rabbi, Bernie can. He reads his grandfather’s story and through it, discovers his past and redefines his future. Through every absurd twist this tale has taken (and there are many), Bernie has found his way by finding his Jewish ancestors. Those are his people. They are his stories. And they are Southern, even though it took me much too long to recognize them as such.

[Read Chapter 16‘s 2011 interview with Steve Stern here and find out more about the 50 Books/HT50 project here.]

Sara Beth West got fired from her first job. By her dad. Since then, she’s walked away from many other jobs, including nanny, retail worker, farmhand, choir director, teacher, social media manager, and compost truck driver. Most recently, she left a great job as a public librarian. But the one job that keeps following her around is writer. She writes book reviews and conducts author interviews for Shelf Awareness, Chapter 16, Southern Review of Books, and more. She lives in Chattanooga.