A Multitude of Elegies

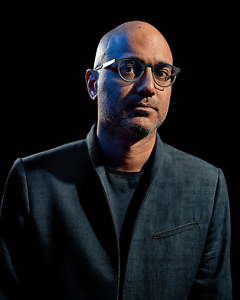

Ayad Akhtar creates a powerful literary assemblage in Homeland Elegies

Autofiction is fictionalized autobiography that maneuvers around the rooms of the author’s life, arranging a vase here, imagining a divan there, relieved of the memoirist’s burden: Did I get it down right? Two-thirds of the way through his dazzling, genre-busting Homeland Elegies, Ayad Akhtar reveals that this is his game: “I can’t renounce this bizarre tendency simply for the sake of preserving what little reliability I may still possess as narrator of these songs and stories; I have to own it; this brand of crazy is fully baked into me.”

What emerges is similar to a Calder mobile, an original assemblage of bright colors and jagged shards that move and twirl into a coherent, strikingly beautiful whole.

Akhtar opens during the 2016 Republican primaries as his recently widowed father — a Pakistani immigrant and physician who treated Trump for a heart condition years before — inexplicably falls for the reality-show huckster turned presidential candidate. Something about Trump’s xenophobia awakens the id of the elder Akhtar, who rails against Christians, Jews, and Muslims alike, disdains Black people for their perceived “slave’s mentality,” and puts down women who, like Hillary Clinton, have sought careers outside of the home.

Ayad connects his father’s rants to a larger national breakdown:

[T]he man seemed to be turning into an imbecile, his hodgepodge views like mental flatulence, one fetid odor after another. To push the metaphor: it had the logic of dysentery, an infection of his political consciousness occasioning wanton discharge. And further: a child shits on the floor and sticks its finger in the feces, delights in the odor, and relishes the disgust in everyone else. Puerile pleasures, that’s what Father was learning again — we all were — and Trump was our tutor.

From this moment of sickening disillusion, Homeland Elegies unfolds across a mash of forms, from family saga to political op-ed to Muslim history. Akhtar’s parents, both doctors, came to the United States to work. Ayad was born in Staten Island and grew up in suburban Milwaukee, yearning to be a writer. After studying literature at Brown and playwriting at Columbia, Ayad rented a small one-bedroom apartment in gentrifying Harlem and won the 2013 Pulitzer Prize for Disgraced. His conflicted feelings about America pulse throughout these pages, a 21st-century version of a Twain-like tall tale.

He relies on a series of ornate, digressive set pieces to propel his book forward — no graceful arc for him. As with Junot Díaz’s The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao, the narrative proper may be a farce, with the real action unfolding in a series of carefully inserted footnotes. Each section conjures its own erudite magic. A bottle of Saint-Émilion with a literary aunt who loathes Rushdie; racist encounters in Scranton, Pennsylvania, after his car breaks down; a visit to impoverished relatives in Pakistan — all gleam in a lush, adventurous prose. There’s danger here, including scenes of graphic sex — one involving an STD and a gray Icelandic mitten — as Akhtar skewers Puritan sensibilities, as well as conservative Muslim attitudes, dissecting all aspects of our smug American morality.

He relies on a series of ornate, digressive set pieces to propel his book forward — no graceful arc for him. As with Junot Díaz’s The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao, the narrative proper may be a farce, with the real action unfolding in a series of carefully inserted footnotes. Each section conjures its own erudite magic. A bottle of Saint-Émilion with a literary aunt who loathes Rushdie; racist encounters in Scranton, Pennsylvania, after his car breaks down; a visit to impoverished relatives in Pakistan — all gleam in a lush, adventurous prose. There’s danger here, including scenes of graphic sex — one involving an STD and a gray Icelandic mitten — as Akhtar skewers Puritan sensibilities, as well as conservative Muslim attitudes, dissecting all aspects of our smug American morality.

And nowhere are we more self-satisfied than with money. In one beguiling episode, Akhtar drifts into an unexpected friendship with a rich-as-Croesus Pakistani American, a hedge-fund manager. Riaz’s millions act like an aphrodisiac to Ayad: private jets, trips to villas in Italy, rare Japanese whiskey. But there’s no pot of gold at the end of the billionaire’s rainbow, only a disgust with self, as Ayad realizes during a conversation with his friend in a lavish Upper East Side apartment: “Night had fully fallen over the East River, and the lights along Astoria’s waterfront twinkled, sparse, serene. Riaz stood and emptied what was left of that sublime whiskey into our tumblers. Throughout his telling, I’d watched the flashing anger in his eyes grow stronger, steadier, watched the incandescence of his rage brighten and consume some essential kindling that, now spent, left him looking enfeebled.”

Ayad confesses, too, his lack of a fulfilling relationship with his father and, more poignantly, with his reserved mother. Such moments of vulnerability enrich our understanding. Homeland Elegies, then, is a multitude of elegies: for Akhtar’s ancestral Pakistan, for an America that’s lost its way, for Islam, for his youth, for the act of storytelling itself. And yet here he’s forged something vivid, compelling, and possibly new. “Maybe I just needed to be encouraged to step outside of my comfort zone,” he opines. But he’s also aiming his criticism at us, in dire need of just such a book to shock us from our complacency and toward those better angels we desperately want to believe in.

Hamilton Cain is the author of This Boy’s Faith: Notes from a Southern Baptist Upbringing and a frequent reviewer for O, the Oprah Magazine; the Minneapolis Star Tribune; and The Barnes & Noble Review. A native of Chattanooga, he lives in Brooklyn, New York.