A Newly Shattered World

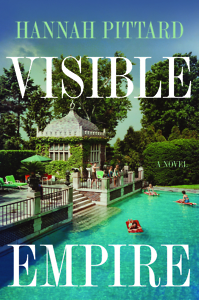

Hannah Pittard’s Visible Empire gives a fictional account of 1962 Atlanta, rich and poor

On June 3, 1962, Air France Flight 007, bound for Atlanta and then Houston, crashed during take-off from Orly Airport. All 122 passengers and all but two of the flight crew were killed; at the time, the crash was the worst single-aircraft disaster in history.

The tragedy hit Atlanta especially hard; 106 of the passengers were members of the city’s cultural and artistic elite, on their way home from touring the great museums of Europe. In an instant, most of Atlanta’s most prominent citizens were killed. Visible Empire, the fifth novel from native Atlantan Hannah Pittard, catalogues the crash and its terrible aftermath, spinning out a story of grief, loss, and racial unrest over the course of one fateful summer in the rapidly changing South.

The tragedy hit Atlanta especially hard; 106 of the passengers were members of the city’s cultural and artistic elite, on their way home from touring the great museums of Europe. In an instant, most of Atlanta’s most prominent citizens were killed. Visible Empire, the fifth novel from native Atlantan Hannah Pittard, catalogues the crash and its terrible aftermath, spinning out a story of grief, loss, and racial unrest over the course of one fateful summer in the rapidly changing South.

For readers compelled by the history of Flight 007, Pittard appends a detailed bibliography, which includes everything from scholarly papers and contemporary newspaper articles to YouTube clips and FBI files. But to convey the cultural and historic backdrop of the story, she sets the stage with several epigraphs. One, from then Atlanta Mayor Ivan Allen, simply states what seems rather obvious: “Atlanta has suffered her greatest tragedy and loss.”

The quotation that follows takes a divergent view. Malcolm X called the crash God’s work. “He gets rid of 120 of them in one whop,” he said, “and we hope that every day another plane falls out of the sky.”

Juxtaposed starkly before the novel even begins, these two remarks offer the first hint that Pittard intends to describe the disaster’s effect not just on the white, rich, cultured elite—the “visible empire” of Atlanta’s ruling class—but also on the city’s disenfranchised. Although her imaginary reconstruction of the summer of 1962 consistently references actual events and real-life individuals, the facts are only a scaffolding for the tale she aims to tell.

Pittard’s characters, whether real or fictive, are a diverse and fascinating bunch. There’s the aforementioned mayor and his semi-invalid wife, Lulu, whose petulant, self-indulgent dialogue (“I won’t do it. You can’t make me. If I have to attend another service, I’ll die”) functions throughout the book as a kind of oracular, formless lament. There’s wimpy, indecisive Robert Tucker, a coward on a drunken bender ever since discovering that his mistress has died in the crash. There’s Robert’s heavily pregnant wife, Lily, and his no-good pal P.T. Coleman, both of whom have lost parents and gained an inheritance vastly different from what they were led to expect. And there’s a beautiful grifter named Anastasia, who feigns bereavement in order to weasel her way into the life of a wealthy aging lesbian-until the tables are turned in an amusing and satisfying episode of poetic justice.

Pittard’s characters, whether real or fictive, are a diverse and fascinating bunch. There’s the aforementioned mayor and his semi-invalid wife, Lulu, whose petulant, self-indulgent dialogue (“I won’t do it. You can’t make me. If I have to attend another service, I’ll die”) functions throughout the book as a kind of oracular, formless lament. There’s wimpy, indecisive Robert Tucker, a coward on a drunken bender ever since discovering that his mistress has died in the crash. There’s Robert’s heavily pregnant wife, Lily, and his no-good pal P.T. Coleman, both of whom have lost parents and gained an inheritance vastly different from what they were led to expect. And there’s a beautiful grifter named Anastasia, who feigns bereavement in order to weasel her way into the life of a wealthy aging lesbian-until the tables are turned in an amusing and satisfying episode of poetic justice.

These are Pittard’s white people: each with a secret existence that belies his or her genteel exterior, caught up to various degrees in the dark underbelly of Atlanta’s social life.

Pittard’s black characters, by contrast, mostly hover in the background, with one compelling exception. Piedmont Dobbs, a nineteen-year-old whose application “to be among the first Negro students to matriculate into Atlanta’s all-white public school system” is denied, decides “that the city had it coming.”

Everything changes for Piedmont when Robert Tucker and P.T. Coleman hire him to drive Coleman’s convertible on a mysterious errand one scorching summer night. And just like that, Piedmont’s lot is cast with the white people in the newly shattered world where tragedy has blurred or obliterated the lines that kept its social strata apart.

Piedmont’s sudden immersion in the world of Atlanta’s moneyed elite mirrors Anastasia’s deliberate invasion of the same milieu, but cultural trespass has vastly different implications for a white woman than for a black man. For Piedmont, the stakes are perilously high; simply walking in the wrong neighborhood puts him in mortal jeopardy. But he is far from radicalized, wondering “if it was okay to sit back, keep his head down, and wait for whatever improvements those around him might acquire on his behalf.”

But indifference to the civil-rights movement in no way insulates him from the constant, automatic, and thoroughly institutionalized racism that permeates the South in 1962. When Piedmont has control of Visible Empire‘s narrative, the reader feels tense and anxious; reading Piedmont’s chapters, it’s impossible to forget it’s 1962.

The chapters narrated by white people, by contrast, feel nearly contemporary. To orient us, Pittard works period details into background descriptions or overheard conversations, mentioning, for instance, the lack of air conditioning, or the burgeoning Berlin Wall. The effect can be jarring, but it eventually makes an important point. There’s a feeling that change is in the air, as the spectre of profound cultural upheaval hovers just over the horizon. But the fact that so much of Pittard’s novel feels modern points a subtle finger to the many aspects of Southern society—especially that of moneyed, privileged white people—that remain, as we head into the third decade of the twenty-first century, depressingly intact.

Fernanda Moore has been a contributing writer to Chapter 16 since 2009. From 2013 to 2016, she was the fiction critic for Commentary; her work has also appeared in The New York Times Magazine, Marie Claire, New York, and Southern Living, among others.