A Place for Us

SunAh M Laybourn on her new book exploring Korean adoptee identity

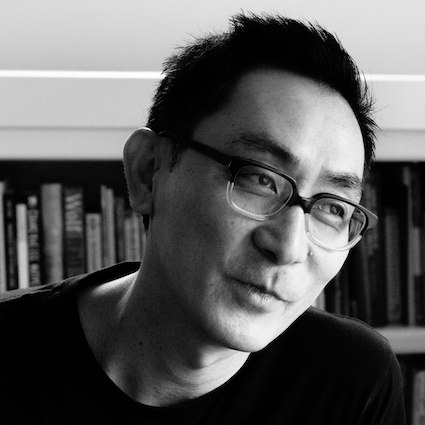

“Although I am a Korean adoptee, my entry into the Korean adoptee community did not begin until this project,” SunAh M Laybourn writes in the acknowledgments to Out of Place: The Lives of Korean Adoptee Immigrants. It’s a notable entry. And if it’s a reader’s entry into this subject area as well, Out of Place is a valuable guide. Over the course of the book, Laybourn, an assistant professor of sociology at the University of Memphis, talks to Korean American adoptees about their experiences, their sense of identity and, importantly, their sense of belonging — or lack thereof, as suggested by the book’s title.

This is no collection of abstract ruminations, though. Laybourn presents theses and evidence, making this a more academic book than many on the subject. As such, in making a case for the unusual situation of Korean adoptees it deploys phrases like “interdependent constructions of citizenship, kinship, and race.” But just because it’s deeply researched and informed by theory, that doesn’t mean Out of Place lacks warmth or empathy, even as it wrestles with big ideas about identity, racism, and grief. Laybourn also skillfully weaves a fair amount of history, policy, and organizing context around the personal narratives. Because adoptees are often rendered invisible, this chorus of voices, carefully recorded and analyzed, is a necessary addition to the literature, allowing adoptees to tell their own sometimes confounding truths. Laybourn answered questions from Chapter 16 by email.

Chapter 16: In the acknowledgements you say that, while you are a Korean adoptee, you were not part of the community until you began this book. Can you talk about what that experience was like for you?

SunAh M Laybourn: The prospect of finally finding your people after having grown up learning that searching was futile was both exhilarating and terrifying. There was that initial sense of excitement followed by a fear of rejection. As I think back on it now, I’d say it was more precisely a feeling of questioning my self-worth. As in, what if the people who I think I should have some commonality with, the people who I think I should feel some sense of belonging to, what if I don’t belong there either? What does that then say about me? At my core, is there something wrong with me? That line of questioning speaks to the sense of shame I carried within me for so long.

In terms of growing up without a Korean adoptee community, it was isolating in a way that is difficult for non-transnational transracial adoptees to fathom. It’s just so outside of their realm of understanding. Because, while it’s true that I was a part of a family, a part of a church, a part of various extracurricular activities and friend groups and many other groups, there is something about not sharing DNA with your family and also not being part of a same race, same ethnicity community that can feel very isolating. Society tells us that “real” family is defined by shared blood, and in U.S. society, race is such an organizing feature that without having an anchoring in either, it can be easy to feel adrift despite the many other connections one may have.

Chapter 16: When I was a child, I felt basically white, for lack of a better term. But I was somewhat taken aback by adult adoptees who describe still identifying that way, to the point that they would check “white” on a form. As you were interviewing people, what surprised you?

Laybourn: Definitely folks who remain so strongly affirmed in a white identity because that is not something that I could or would want to do, though I understand why folks do. If part of family belonging is predicated upon having a shared racial experience, then it makes sense. If part of national belonging is predicated upon being categorized as white, then it makes sense — and, in fact, we see throughout history, different folks staking claims to whiteness because they understood that citizenship rights were linked to being classified as white.

But what surprised me the most was hearing people say they identified as an adoptee. When I first started my research, I was new to the community myself, so to have “adoptee” as a possibility for how I could identify was peculiar. It never occurred to me that “adoptee” was something that I could be — that being adopted could be more than simply an explanation for how I came to be in this country, in this family, that it could be the basis for a shared group identity with shared experiences. That’s why I had to include Harry’s quote to open Chapter 4: “Korean plus something else.” I remember that conversation vividly, and it was such the perfect time for me to have it with him. Because I was so new to the community, I could really be curious and unpack what this identity meant for people in a way that other folks who may have been in the community would have taken for granted.

Chapter 16: What differences did you notice between different generations or other demographic groups within the Korean adoptee community?

Laybourn: Something that stood out to me was that some of the differences between generations weren’t as sharp as one might hope. For example, Korean adoptees still growing up feeling white, still being raised with little connection to other adoptees and/or other Asian Americans — that was a patterned feeling across adoptees regardless of age or decade of adoption. There were differences between how women and men Korean adoptees talked about dating and some of the expectations of femininity/womanhood and masculinity/manhood. I couldn’t go as in-depth about those differences in the book as I would have liked, but in general I saw how the racialized and gendered stereotypes about Asian women and men were playing out in adoptees’ lives. For example, many women adoptees explicitly talked about being sexualized and men having an “Asian fetish” toward them. While men talked about feeling as though they were unattractive.

Laybourn: Something that stood out to me was that some of the differences between generations weren’t as sharp as one might hope. For example, Korean adoptees still growing up feeling white, still being raised with little connection to other adoptees and/or other Asian Americans — that was a patterned feeling across adoptees regardless of age or decade of adoption. There were differences between how women and men Korean adoptees talked about dating and some of the expectations of femininity/womanhood and masculinity/manhood. I couldn’t go as in-depth about those differences in the book as I would have liked, but in general I saw how the racialized and gendered stereotypes about Asian women and men were playing out in adoptees’ lives. For example, many women adoptees explicitly talked about being sexualized and men having an “Asian fetish” toward them. While men talked about feeling as though they were unattractive.

Chapter 16: There’s a pretty robust discussion of media in the book, including adoptee-directed films and Justin Chon’s Blue Bayou, which was criticized by some adoptees for borrowing heavily from Adam Crapser’s deportation story without credit. How do you see the importance of representation when it comes to Korean adoptees?

Laybourn: When I was a child, I thought being an adoptee — and I don’t think I even thought of myself as an “adoptee” but rather “adopted” — I thought that meant I was deficient, less than, unwanted, unlovable. I very much identified with or looked to media to help me make sense of being adopted or more specifically being abandoned. There weren’t many representations, and the ones that stick out were animated movies; An American Tail comes to mind and The Land Before Time. As an impressionable child, these movies emphasized a variety of harmful beliefs about what it meant to be adopted, or rather what it meant to be separated from biological family. Without representation and without nuanced representation, what stands in? How differently would I have made sense of being adopted had I had [films like] aka Dan, aka SEOUL, Twinsters, Geographies of Kinship, or First Person Plural? While I don’t think it’s possible to have one singular form of media that captures the intricacies of the adoptee experience — and I think that’s an unfair expectation to put on one media — having media that expands portrayals of adoption beyond the Hallmark conceptions of “forever family” or “love is thicker than blood” would have been so beneficial.

When Joy Ride came out, which has a female Asian adoptee plotline, I was part of a group of adoptees who created a best practices guide for journalists when covering adoptee-related media/events. The cultural assumptions about family, adoption, and adoptees are so strong that adoption continues to be an easily exploitable plot device without regard for adoptees’ actual lived experience. Ultimately, I’d like to see a variety of media that delves into the full range of adoptee personhood.

Chapter 16: Over the course of these interviews, and putting the book together, did you feel like anything changed in your understanding of the overall Korean adoptee experience — or your own?

Laybourn: Something that I continue to think about is the common experience of adoptees not feeling like they are part of the adoptee community even as they are actively participating in it. For example, I would often hear folks with a “positive” adoptee experience say they felt like the community was defined by those with a “negative” experience. And folks with a “negative” experience felt like the community was defined by those with a “positive” experience. I can’t help but wonder if that is the adoptee experience — to not be able to see yourself as part of a community or to be so used to not being a part that you’re always looking for the way you don’t belong. I wonder if it can be a protective mechanism — to not fully allow yourself to feel secure in your belonging because you’ve experienced so many instances of later being made to feel like you were never truly a part.

For me, being able to connect with other Korean adoptees has been life changing, and I’m careful to not put unrealistic expectations on the community. What I mean is that the adoptee community is imperfect, it’s messy, it’s complicated, and it kinda has to be … because all communities are. To truly belong is to be able to be in the messiness and complexities of it all.

Steve Haruch is the senior producer for the Nashville Banner. He is the editor of the books Greetings from New Nashville: How a Sleepy Southern Town Became ‘It’ City and People Only Die of Love in Movies: Film Writing by Jim Ridley.