A Pleasure, Not a Chore

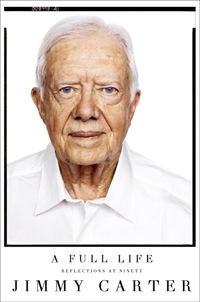

President Jimmy Carter talks with Chapter 16 about his new memoir, A Full Life: Reflections at Ninety

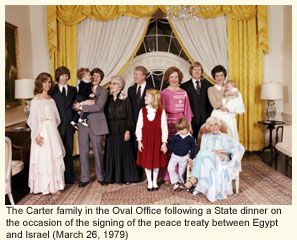

Jimmy Carter was fifty-two years old when he was elected president of the United States in 1976. His time in the White House was, as he puts it, “the pinnacle of my political life,” but they were only four years in a life built of service—to his family, to his faith, to his country, and to the world—that has now spanned more than nine decades. This is Carter’s twenty-ninth book, but in his new memoir, A Full Life: Reflections at Ninety, he looks back for the first time across the full span of his life, from his childhood in Plains through his years in the Navy and his return to the family farm in Georgia, from his political career to his later philanthropic work with the Carter Center. Through it all, as example after example suggests, he took solace from his Christian faith, his family, and—perhaps surprisingly for a man trained as a nuclear engineer—his painting and his poetry.

Carter recently spoke with Chapter 16 by phone in advance of his signing at the Nashville Public Library on July 23:

Chapter 16: You’ve already written more than twenty books; why have you decided now to do a career-and-life retrospective?

Chapter 16: You’ve already written more than twenty books; why have you decided now to do a career-and-life retrospective?

Jimmy Carter: This is actually my twenty-ninth book, and I’ve enjoyed writing them. They’ve been on a wide range of subjects, and I thought now that I’ve passed my ninetieth birthday that I would just go back and look at my whole life in general and some of the things that have never been covered before, like my time in the Navy, life on a submarine, why I ran for president, what my relationship was with other former presidents, and what are the successes and disappointments I had when I was in the White House. And also what lessons I’ve learned at different phases of my life, lessons I learned about the race issue when I was a young man in Plains on a farm near Archery, Georgia, and what was my relationship with my wife, and things of that kind that I drew a lesson from, and some of the lessons that I have learned that may be helpful to others.

Chapter 16: In the book you mention that your mother had a very progressive view of race back when you were growing up, but your father wasn’t quite as enlightened. Where do you think her progressive stance came from?

Carter: Well, my grandfather, my mother’s father, was quite progressive on the race issue, but my mother did it on her own. She was blessed in two ways: one, she had a very independent spirit. Nobody told her what to do. She had a mind of her own. And the second one was that she was pretty well protected from criticism by her role as a registered nurse. Plains, Georgia, had a very wonderful hospital, and doctors and nurses were almost worshipped, or revered, in our town. Since Mother departed from the usual provisions of racial distinctions and separation, she got away with it because she was a registered nurse. So she was just able to implement her own basic beliefs that black and white people should be treated equally.

Carter: Well, my grandfather, my mother’s father, was quite progressive on the race issue, but my mother did it on her own. She was blessed in two ways: one, she had a very independent spirit. Nobody told her what to do. She had a mind of her own. And the second one was that she was pretty well protected from criticism by her role as a registered nurse. Plains, Georgia, had a very wonderful hospital, and doctors and nurses were almost worshipped, or revered, in our town. Since Mother departed from the usual provisions of racial distinctions and separation, she got away with it because she was a registered nurse. So she was just able to implement her own basic beliefs that black and white people should be treated equally.

Chapter 16: With the recent tragedy of the shooting in South Carolina, what do you make of the attempts to remove the Confederate battle flag from public spaces in the South? Do you agree with those attempts?

Carter: I do agree with it. This was done in Georgia, maybe twelve or so years ago. The Democratic governor who did it, Roy Barnes, who was a wonderful governor, was defeated for reelection because he did that, and so you still have some remnants of that carryover, which is kind of political in nature all throughout the South—in Alabama, South Carolina, and so forth. There’s no doubt that the Confederate battle flag, as interpreted, is a symbol of racism. And my hope is that South Carolina and other states will make a decision to let the flag be revered in museums and in public displays of an historical nature, but not let it be a symbol of priority between white and black people.

Chapter 16: Now, let’s go back to your youth. When you were ten years old, did you envision what your life was going to be like?

Carter: When I was ten years old, if you’d asked me, “What do you hope to be when you grow up?” I would say, “I want to go to the Naval Academy and be an officer in the Navy.” The reason for it was that nobody in my daddy’s family had ever finished high school before, down through thirteen generations in this country. There were only two free universities about which we were familiar. One was West Point and the other was Annapolis. My daddy had been in the Army, but he didn’t have any allegiance to the Army. My favorite uncle was still in the Navy, so I would say, just like a parrot, I’d want to go up to the Naval Academy. That was the only thing that I wanted to do. My teachers and parents knew it, so they kind of held that over my head as a challenge to do well in my studies and not let anything prevent my going to Annapolis.

Chapter 16: And when you graduated from Annapolis, what how did you envision your life from that point on?

Chapter 16: And when you graduated from Annapolis, what how did you envision your life from that point on?

Carter: I was going to serve thirty years in the Navy and retire, either in Hawaii or maybe around Annapolis somewhere. That was my ambition in life, and that was the only thing we had in mind when I finished at the Naval Academy. I had to serve in battleships for two years when I finished because I drew a very low priority number, but ultimately, of course, I went into the submarines, and that was my chosen profession.

Chapter 16: Later in your political career—you wouldn’t take it as an insult—many people tried to call you “that peanut farmer” as a way to denigrate you. Are you upset that more people don’t know about your technological role in the Navy?

Carter: No. As a matter of fact, I used the peanut-farmer role when I ran for governor because I ran against a very rich lawyer, and one distinction that I drew between me and him was that I was a working man, that I’d grown up on a peanut farm and still lived there. In fact, I was a full-time farmer when I ran for public office. I had been full-time for seventeen years, so I was very proud of that, and we still have the same farms we had back in those days—the oldest farm since 1833 in the family, and the newest farm since 1904. On the farm we still grow peanuts, cotton, pine trees, wheat, sorghum, and so forth like that.

Chapter 16: But you want people to know that you were instrumental in bringing nuclear reactors onto naval ships….

Carter: Well, when I ran for Georgia senator—I’ve looked at my old campaign notices, I’ve still got a few of those, and I point out that I’m a working farmer and also that I did graduate work in nuclear physics, and that I went to Georgia Tech, so I wanted people to know that I was at least well educated, as well as a hard-working man.

Chapter 16: But you were on the cutting edge of technology when you were working for Admiral Rickover.

Carter: I was. I had the most unique job in the world. I was a trained nuclear engineer when we were building the second atomic submarine power plant in the world. I had top-secret clearance, and I had a lot of advantages in the Navy. As you say, I was on the cutting edge of the most modern technology, all designed, according to Rickover, to work for peaceful purposes. We wanted to have nuclear power to be available to generate electricity, to provide medical treatment, and also to propel ships.

Carter: I was. I had the most unique job in the world. I was a trained nuclear engineer when we were building the second atomic submarine power plant in the world. I had top-secret clearance, and I had a lot of advantages in the Navy. As you say, I was on the cutting edge of the most modern technology, all designed, according to Rickover, to work for peaceful purposes. We wanted to have nuclear power to be available to generate electricity, to provide medical treatment, and also to propel ships.

Chapter 16: It seems you have lived such a well-balanced life. You’ve studied science, hard science, but you’ve also been involved in the arts—in writing your poetry and painting—in addition to politics. You’re a very strong man of faith and a family man. Can you imagine a more well-rounded life out there?

Carter: I’ve had a full life, and I didn’t say that as a way to brag on myself—just to point out how fortunate I have been. I’ve had some setbacks and disappointments, obviously, in my life. But I was taught quite early in my life by my schoolteachers and by my parents, if I did have a mistake, failure, or disappointment, to try to get over it in a hurry and set an even higher ambition for the future, so that’s been the kind of thing that I’ve tried to pursue. And it’s worked most of the time for me. I pointed out in the book that there were a lot of times that I didn’t get what I wanted, particularly when I was president, a lot of things that I wanted to resolve permanently, and either because the priorities of our nation changed or because of circumstances and so forth, I was not able to do the things I wanted to do.

But I think that we have a great country, and we have the potential to be the number-one nation in the world in all the aspects of life, in peace, which we have not achieved, in human rights and democracy, freedom, environmental quality, generosity. All those things are moral standards that our country has the potential of being preeminent in accomplishing.

Chapter 16: What do you think is going to be the biggest challenge for the president who will be elected in 2016?

Chapter 16: What do you think is going to be the biggest challenge for the president who will be elected in 2016?

Carter: Well, I think helping to bring peace and equalizing the opportunity of people in this country and around the world. We’ve seen a major setback in our democratic system in the last fifteen years, and we’ve seen a tremendous setback in the equality of opportunity to advance one’s role in life in the last thirty years. We’ve seen a six-fold increase in people in prison since I’ve left the White House. I think I pointed out in the book the 800 percent increase in the number of black women in prison. Unfortunately, we still have the death penalty in our country, and we are the number-one country in the world committed to going to war to achieve our goals. We’ve been to war with about thirty countries since the Second World War. So, we have a long way to go, but we have the kind of society, with our constitutional provisions built in, that gives us a strong inclination to have a self-correcting of our own setbacks and disappointments.

Chapter 16: In 2009 you wrote an essay about leaving the Southern Baptist Convention back in 2000, but last year it really caught on as a huge viral sensation on the Internet. What does it feel like to be always a man ahead of your time?

Carter, laughing: Well, I can’t say that I’m always a man ahead of my time. When I left the White House, I tried to bring together the different conflicting elements within the Southern Baptist Convention. I had two major sessions to try to do this, but all those hopes were dashed, for me at least and for my wife, in the year 2000, when the Southern Baptist Convention ordained that we have something of a creed that we have to comply with. Part of that creed is that women cannot have an equal role in the affairs of the church, as chaplains in the military, as deacons, as priests or pastors, and in some Southern Baptist seminaries, the Southern Baptists even say that a (woman) professor in a seminary, a college, can’t teach a class if there’s a boy in the room. That was contrary to my basic belief of what Jesus Christ taught, so in a very quiet way then, we just totally withdrew from the Southern Baptist Convention.

Chapter 16: And your sister, Ruth Carter Stapleton, was a noted evangelist in her time.

Chapter 16: And your sister, Ruth Carter Stapleton, was a noted evangelist in her time.

Carter: She was the finest Christian I have ever known personally. She had a way of using her faith in Christ in a very humble and relaxed way that put people at ease. She didn’t preach to people, but she reached out to drug addicts, alcoholics, and people who had marital problems and psychological problems to try to minister to them, so she was a very admirable person.

Chapter 16: How do you think that you’ve been able to honor the spirit of your faith while not being caught up in the letter of doctrine?

Carter: Well, I fumbled along with my faith, like most other people do. My life is not full-time committed to serving Christ in a church capacity, but I teach every Sunday. I taught yesterday, and I’ll teach next Sunday, teach the Bible in our little church. We have about thirty members regularly in our church, and sometimes several hundred visitors come to hear me teach. Part of it is just a politician teaching the Bible is kind of a curiosity thing, but a lot of the folks who come to my church as visitors tell me that they haven’t been to church before, or they haven’t been in twenty years, so it’s a partial ministry that I have. I really enjoy it and get a lot out of it myself. In fact, I started teaching Sunday school, like my father did before me, when I was a midshipman in the Naval Academy. I taught Sunday school every Sunday while I went to Annapolis.

Chapter 16: Art has also been a big part of your life. You’ve published a book of poetry, and the new book includes several poems as well as several of your paintings. What role do the arts play in nourishing your soul?

Carter, laughing: It’s just like a hobby. I like to stay busy. I like to stretch my mind and stretch my heart, as I say often. And so I’ve always been challenged by designing things and building things of my own. I did that when I was in the Navy, in hobby shops around the world—Hawaii, Norfolk, New London, so forth. When I was president, I used the wood shop at the White House and at Camp David. So I am either writing a book, painting a picture, or building a piece of furniture, in addition to my duties as a professor at Emory University—just finished my thirty-third year there—and also the work I do at the Carter Center. So I like to stay busy, but I like to stay busy doing things I really enjoy, not as a chore but as a pleasure.

Chapter 16: Your daughter Amy holds degrees in art from the Memphis College of Art and Tulane University—does she give you any tips on your painting?

Chapter 16: Your daughter Amy holds degrees in art from the Memphis College of Art and Tulane University—does she give you any tips on your painting?

Carter: On occasion, in kind of a quiet way. Amy is very timid about that, but I look at Amy’s paintings and admire them. She is a much more accomplished painter than I. I’ve never had any lessons. I have a granddaughter, Sarah Elizabeth, who is a professional artist full time; she lives in Los Angeles. When she comes to visit me, or Amy does, I always welcome their suggestions, but I have to admit that I think they are reluctant to give me suggestions.

Chapter 16: And soon several of your paintings will appear in a coffee-table book.

Carter: The book is just finished, as a matter of fact. I’ve written about fifty or sixty paintings, why I painted that particular scene or person and what they meant to me and what kind of canvas or Masonite I used, what kind of paint—so a little bit about the painting, why I painted it, and the technique I used. I think it’s going to be interesting. I gave it to the Carter Center, by the way. So the people at the Carter Center, whom I have some influence on but do not control over, they’ll decide when to sell it and probably to raise money.

Chapter 16: In A Full Life you do give some opinions on other presidential administrations that have come since yours, but what do you think of George W. Bush’s paintings?

Carter: I think he’s probably a better painter than I am. I haven’t really seen any of his actual paintings—I’ve just seen pictures of them in the newspaper. But I’m glad he took up painting. As you know, Mr. Churchill painted some, and President Eisenhower was an artist, as well. I’ve got their books, so I admire what other people do. I don’t really compare them to me. I think most of them are better painters than I am.

Chapter 16: Now at ninety, what do you envision your life is going to be like?

Carter: You know, we’re prepared for any eventuality. We’ve been lucky, my wife and I both. I’m ninety, soon be ninety-one in October, and she’s three years younger than I am. We’ve been blessed with good fortune, basically, as far as our health is concerned. But we expect to stay as busy as possible. I realize, though, that my main job now, which is to run the Carter Center, is going to have to pass on to other people. My grandson, Jason Carter, is going to be the new chairman of our board of trustees beginning in November. So, other people in our family will take over the responsibilities. We have programs in about eighty countries in the world, so we stay pretty busy at the Carter Center, and teaching at Emory. So we’ll have a good life, and when I get to where I’m not able to travel around, I’ll maybe spend more time painting pictures and building furniture.

To download the podcast click here. To listen online, click the play button below:

height=”50″ width=”325″ scrolling=”no” allowfullscreen

webkitallowfullscreen mozallowfullscreen oallowfullscreen

msallowfullscreen>

Stephen Usery is the producer of Book Talk, an author-interview program that airs daily on WYPL FM 89.3 and is sponsored by the Memphis Public Library. Usery also produces Mysterypod, an independent podcast focused on mysteries, thrillers, and crime novels. He lives in Memphis.