A Poet of the Heart

Remembering Arthur Smith (1948-2018)

Arthur Smith came to Knoxville from central California, by way of Houston, Texas, and for more than 30 years he helped poets at the University of Tennessee find the path toward their own voices. He was my professor there when I was an undergraduate in mid-1990s, and then again when he directed my Ph.D. dissertation in the late 2000s. By that time, I had also graduated from thinking of him as my mentor Dr. Smith to calling him my friend Art.

His first book of poems, Elegy on Independence Day, was awarded the prestigious Agnes Lynch Starrett Prize from the University of Pittsburgh Press and the Norma Farber First Book Award. He would go on to publish three more books of poems. Many of Art’s individual poems appeared in the most prestigious literary journals, such as The New Yorker, Poetry, and Kenyon Review. Despite such acclaim, Art was modest about his accomplishments. His ambition was devoted strictly to the poems themselves and never fixated on any recognition they might receive.

Art’s teaching style was both gentle and exacting. He could lead a poem toward its next draft without over-directing where it should go, and his reflections about phrases and images all circled back to an essential question: “Does it serve the poem?” While he had a comprehensive knowledge of the modes and measures of poetry from the ancient Greeks to current literary journals, Art loved the poets of the heart most of all. In class, he often referred to the fragments of Sappho, the Odes of Horace, Emily Dickinson, James Wright, Linda Gregg, and always Jack Gilbert, whom he brought to campus as a visiting professor for the spring semester of 2004. Many of Art’s proteges have gone on to publish books, and several of us now teach classes of our own. My poetry students at ETSU are all familiar with Art’s ultimate question, and they know where it came from: “What is at stake in this poem?”

Art’s own poems were models of how to gracefully examine our strongest and most chaotic feelings of love and grief. Their elegant structures felt casual and unassuming, yet the craftmanship was apparent in the subtle emphasis added by his perfect line and stanza breaks. Art’s second collection of poems, Orders of Affection, was published in 1996, when I was a student in his class. It was thrilling to read my teacher’s work published in such a beautiful book, and that volume became my permanent template and standard for what a book of poetry should be. I remember feeling so proud to be studying with the man who wrote those poems that I loaned my copy to my mom.

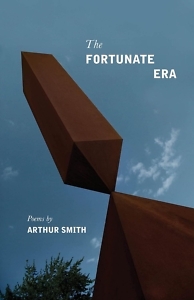

Art’s poems moved seamlessly between the local and the cosmic. In his brilliant final volume, The Fortunate Era, he writes about his California childhood in “Paradise,” one of the best poems of place I have ever read. It opens with beauty and wit, perfectly braided: “I used to live there, I was born there, every morning / The downtown streets were cobbled with gold, honey / Flowed — all that stuff. I’m not kidding.” The poem, like many of Art’s, arrives at the realization that there is such abundance in the world we cannot even absorb it: “All that sugar coaxed out of clay, and you / Can’t even give it away — and each dawn more / Was just piled on. I took in as much / As I could, like larder, and walked away.”

Art’s poems moved seamlessly between the local and the cosmic. In his brilliant final volume, The Fortunate Era, he writes about his California childhood in “Paradise,” one of the best poems of place I have ever read. It opens with beauty and wit, perfectly braided: “I used to live there, I was born there, every morning / The downtown streets were cobbled with gold, honey / Flowed — all that stuff. I’m not kidding.” The poem, like many of Art’s, arrives at the realization that there is such abundance in the world we cannot even absorb it: “All that sugar coaxed out of clay, and you / Can’t even give it away — and each dawn more / Was just piled on. I took in as much / As I could, like larder, and walked away.”

November 9, 2018, in Knoxville was a day of sudden downpours and tearful, unexpected farewells. Art’s friends and colleagues gathered that morning at Park West Hospital. Curt Rode flew in from Texas to be there, and David Kitchel drove over from Nashville and had spent the previous week managing Art’s medical plan. I half-slept the night before in a chair in the overcrowded sadness of the intensive care waiting room. I left a joyful celebration of another East Tennessee poet, Lynn Powell, at Emory & Henry College in Virginia the evening before because I could not bear the thought of not getting to say a final thank you and goodbye to Art, who more than anyone showed me how to pursue a life with poetry at its very center.

I had seen Art so recently, on a mid-October Saturday when I stopped with him on my way to the Southern Festival of Books in Nashville. We had been there together a few years earlier, when he gave a reading from The Fortunate Era. This time I was reading poems from Specter Mountain, the poetry volume I co-wrote with William Wright, and which we had dedicated to Art. I intended to spend only an hour or two in Knoxville, but we ended up having lunch, watching a UT football game (we won!), walking his three impossibly beautiful Keeshonden dogs around the yard, and as always, studying the books spread across his dining room table. We had such a great afternoon that it stretched into evening, and I found myself staying for dinner and getting to my hotel in Nashville at nearly midnight.

When I received a phone call just a few weeks later letting me know that Art was in the hospital and the prognosis was not hopeful, I could hardly believe what I was hearing. He had not seemed as hearty as usual that October weekend, but hadn’t we just spent a whole day fully engaged in life? We had looked at his notes for an essay on Adam Zagajewski and the great recent poets from Poland. We had gone to two restaurants in one day, and at the second one he mentioned some tests his doctors wanted to run. In recent years, I have experienced both sudden and gradual loss of people dear to me, and the former is just as awful as the latter. I loved my friend, my mentor, the first and last reader of my poems. I will miss him forever, but many of us continue to share and celebrate the generous way he encountered the world, and how he offered it back to us in words that carried as much of his self as his fingerprints. Art Smith’s absence grows larger with time, yet the gift of his work remains.

*Previously unpublished work by Arthur Smith recently appeared in Appalachian Places.

Jesse Graves is the author of four poetry collections, including Merciful Days, and a collection of essays, Said-Songs: Essays on Poetry and Place. His work received the James Still Award for Writing about the Appalachian South from the Fellowship of Southern Writers and two Weatherford Awards