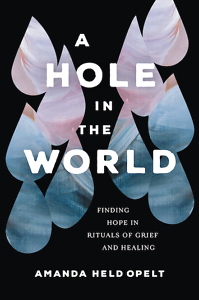

A Portrait of Grief

Amanda Held Opelt reconciles faith and grief in A Hole in the World

“Rituals introduce a healthy rhythm of exposure to grief,” writes Amanda Held Opelt in her debut memoir, A Hole in the World: Finding Hope in the Rituals of Grief and Healing. Opelt, who started her career as a social worker serving in the humanitarian aid sector in places like Iraq and India, wrote the book after the sudden death of her sister, bestselling author Rachel Held Evans.

The sisters grew up in Dayton, Tennessee, and Evans became a voice for post-evangelicals addressing the tensions of identity and ideology, faith and doubt. She documented her maturation as a Christian and her evolution in understanding Christian traditions through five memoirs before succumbing to a fatal infection in 2019 at the age of 37.

The sisters grew up in Dayton, Tennessee, and Evans became a voice for post-evangelicals addressing the tensions of identity and ideology, faith and doubt. She documented her maturation as a Christian and her evolution in understanding Christian traditions through five memoirs before succumbing to a fatal infection in 2019 at the age of 37.

This death and other experiences of loss — the death of her grandmother in 2016, a series of miscarriages, work as a staff chaplain at a combat hospital in Iraq — reoriented Opelt’s approach to her faith. “’It’s not a religion! It’s a relationship!’ As an evangelical in America, I heard this a lot growing up,” she writes. “In this season of grief, I’ve found that my relationship with God did not always help. But my religion did.”

In the book’s introduction, Opelt, a fan of casual praise worship, describes attending an Ash Wednesday liturgy of the Episcopal denomination that once was meaningful to her sister. Its formal beauty opens a path of solace for Opelt, who sets out to research mourning rituals throughout history. The book is organized in chapters addressing these topics with titles like “Keening (Anguish),” “Covering Mirrors (Change),” “Postmortem Photography (Memory),” and “Sympathy Cards (Words).”

Like her sister, Opelt is preoccupied with questions of identity as she tries on different cultural expressions of grief. The most profound writing happens in “Covering Mirrors (Change)” and “Postmortem Photography (Memory).” Opelt understands the wisdom in covering mirrors as a way of domesticating grief, relieving her of the question “Who am I without her?” She writes, “I am often haunted by the old me, the ghost of my former self, my former life. I miss the me who didn’t know in her bones how fragile and frightening life can be.”

Studying the once-popular practice of postmortem photography, Opelt grapples with the mysterious abyss in relationships. Despite the expense and hassle of photography in the 1800s, the sepia-tinged images fulfilled a need to preserve the face of a loved one survivors feared they might forget. “Many times the living would pose with the dead, sometimes creating a first and only family portrait,” Opelt writes, noting how groups of siblings sat around a dead brother or sister surrounded by toys, or mothers held stillborn infants. “In large family portraits, sometimes the only way to tell the living from the dead was to look for the person whose image was the sharpest.” The long exposure times of early photography meant any movement by a subject blurred the image, thus creating a memento that serves as a metaphor for the emotional reality of grief: The lost loved one becomes fossilized while the survivor continues to change and evolve.

Studying the once-popular practice of postmortem photography, Opelt grapples with the mysterious abyss in relationships. Despite the expense and hassle of photography in the 1800s, the sepia-tinged images fulfilled a need to preserve the face of a loved one survivors feared they might forget. “Many times the living would pose with the dead, sometimes creating a first and only family portrait,” Opelt writes, noting how groups of siblings sat around a dead brother or sister surrounded by toys, or mothers held stillborn infants. “In large family portraits, sometimes the only way to tell the living from the dead was to look for the person whose image was the sharpest.” The long exposure times of early photography meant any movement by a subject blurred the image, thus creating a memento that serves as a metaphor for the emotional reality of grief: The lost loved one becomes fossilized while the survivor continues to change and evolve.

Opelt wonders if she is “locked in a flat, achromatic snapshot” of who her grandmother and sister were in the moments of their deaths while her “imagination runs wildly ahead in an infinity of color.” Over time, the memory of her grandmother becomes “less about her and more about me. I make her into a character I can manage in my grief.” Relationships shape us in indescribable ways, and yet we are never fully in control of the path they will take. Opelt wrestles throughout the book with how this is true in our relationships with the living, the dead, and with God.

Opelt finds faith and grief make “strange bedfellows” but are similar in important, intertwined ways.

When her faith felt numbed by doubt, her mind scattered and her heart “shattered by grief,” ritual allowed her to set her body in forward motion.

I made a commitment that I would show up for the liturgy of life with God. I did the same with grief. I set my body in motion. I put on black clothing. I ate casseroles that people delivered. I tore open sealed envelopes and read pastel-colored sympathy cards, taking in every word. … I wandered through cemeteries. I looked through old photographs. I decorated graves with plastic flowers.

What she found was a safe and supportive container for the dual reality of human absence and divine presence — both larger than we can possibly fathom in the present. “Rituals create communal choreography and synchronize our sorrow,” she writes as she appreciates how they “alleviate awkwardness, naming and embracing the elephant in the room.” That container helped her to name and order the chaos of her emotions and invite the community into her sorrow.

Beth Waltemath is a writer and a native Nashvillian. She currently lives in Atlanta, Georgia. Her essays have appeared in The New York Times, The Washington Post, and Chapter 16. She is a full-time journalist for the Presbyterian News Service.