A Right Guy

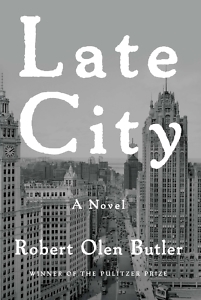

In Robert Olen Butler’s Late City, America’s last surviving WWI soldier reports his life story to God

When a 115-year-old man hears God’s voice late at night, he reasonably expects that the time has come for him to transition to the next world. In the case of Sam Cunningham, the protagonist of Robert Olen Butler’s Late City, God has other plans. In a “mellifluous tenor voice,” God says, “I want you to talk to me, Samuel. About your life. On the record.” God clarifies his instructions in terms that Sam, a journalist, can relate to. “You were a good newsman,” God says. “Just tell it to me straight from your notebook.”

The story that follows traces Sam’s life from childhood in Louisiana to his Army enlistment for World War I and his career at the Chicago Independent. Cunningham’s deathbed recollections coincide with the beginning of one era (the election of the 45th president) and the end of another (Cunningham is the last living veteran of World War I). Strangely, though, Butler chooses not to dwell on the world-historical significance of his hero’s journey. Sam reports on the central issues of his era — segregation, Prohibition, women’s suffrage, the labor movement — but they remain in the background. The novel is more concerned with personal crises in Sam’s family. Sam senses that his confessions are part of his final trial, and he hopes he’s in the hands of a benevolent God.

Among the questions Sam grapples with is the difficult path to manhood. His father, a respected banker in public and an abusive tyrant at home, helps Sam, then 16, lie about his age to join the Army. Oedipal tensions intensify when Sam, an accomplished sniper, returns from the war and must choose between fleeing home to save himself or staying to protect his mother. Looking back at his own record as a father, Sam is confident that he avoided his father’s brand of toxic masculinity but worries, with some justification, that he poisoned his son Ryan with an equally noxious set of prejudices.

Over the course of his dialogue with God, Sam begins to see time from a divine perspective, as a map laid out, all events happening simultaneously. He contrasts the Sam of 1919, “whose long life has barely begun,” with dying Sam, “with this farewell late city edition making its way to press in the twenty-first century.” The title, so apt for a newsman’s final testimony, conveys the novel’s dual interest in looking back and in breaking news. The final printing of the Cunningham Examiner contains shocking revelations, indeed — scoops that Sam’s earlier selves were too oblivious to perceive.

Late City counters the trend in recent fiction of dividing narrative into short chapters, a practice especially common among younger writers eager to retain readers’ attention. Butler, author of 24 works of fiction, takes the opposite approach, offering his story as one uninterrupted whole, a structure that resembles the flow of Sam’s consciousness. “Think of it as dreamstorming,” God tells Sam. “I want you to live your stories just as they felt in their own moment.”

Late City counters the trend in recent fiction of dividing narrative into short chapters, a practice especially common among younger writers eager to retain readers’ attention. Butler, author of 24 works of fiction, takes the opposite approach, offering his story as one uninterrupted whole, a structure that resembles the flow of Sam’s consciousness. “Think of it as dreamstorming,” God tells Sam. “I want you to live your stories just as they felt in their own moment.”

Sam’s memories frequently involve human touch, in manifold variations: his mother’s palm to his temple, his future wife’s hand on his back, the expert caresses of a French prostitute. In the trenches, Sam is repulsed when he sees Johnny Moon, a fellow sniper, kiss a dying French soldier on the forehead. “I do not understand a man kissing a man,” Sam admits. His prejudice returns when Johnny is bleeding to death and reaches for Sam. But Sam, paralyzed with inhibitions, watches Johnny die alone, a failure that deathbed-Sam believes deserves instant damnation. “Go on,” he tells God. “Pull the trigger.” Fortunately, God weighs Sam’s remorse against his momentary weakness; besides, hours remain in Sam’s life, and more people need the comfort of touch.

The ultimate point of Butler’s novel is to ponder the question of the good life. Has he given his wife Colleen love and support, especially when tragedy arrives? He feels guilty for spending evenings away from his family and for thinking constantly about work. “In my head, at least, there is no end to the workday,” Sam says. It’s Al Capone, whom Sam covers on the crime beat, who puts the question most concisely: “Are you a right guy, Sam Cunningham?”

Sam’s father, otherwise an odious hypocrite, phrases the question in terms of personal identity. “We are here to figure out one thing. Who are we? Where do we belong? There has to be a circle around us,” he tells Sam. “Sometimes who’s in that circle is clearly for the best. Sometimes it’s regrettable. But you have to figure out where it must be drawn.”

In other novels, notably Perfume River (2015), Butler explores the devastation that war inflicts on individuals. With Late City, he focuses instead on the inner life of one fallible, lovable, redeemable man over 12 tumultuous decades, a soul forever striving to be a right guy.

Sean Kinch grew up in Austin and attended Stanford. He earned a Ph.D. from the University of Texas. He now teaches English at Montgomery Bell Academy in Nashville.