A Sacred Whole

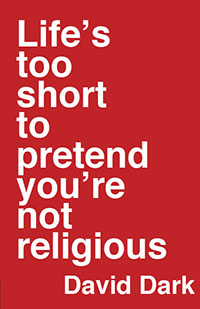

David Dark erases divisions in Life’s Too Short to Pretend You’re Not Religious

Whenever believers and atheists start sniping at each other, someone—usually a would-be peacemaker—will eventually pipe up to declare that everybody has a religion of some sort. We all hold something sacred, this argument goes, even if it’s only the right to hold nothing sacred. This observation, while true enough, doesn’t by itself accomplish much in the way of conflict resolution. At best, it’s a conversation stopper. But in Life’s Too Short to Pretend You’re Not Religious, David Dark sets out to wring some deeper truth from this facile notion and to find the possibilities for connection hidden within the very beliefs that appear to divide us.

Dark’s previous book, The Sacredness of Questioning Everything, seemed to be directed primarily toward younger Christian readers wondering how to protect faith from doubt. (His answer: you don’t have to and shouldn’t try. Doubt is faith’s necessary friend.) Life’s Too Short to Pretend You’re Not Religious, as the title implies, is aimed at a wider audience that includes the confirmed doubter, the person who easily and even with pleasure disavows any worship or faith practice. God and faith as such don’t get much play at all here. Instead, Dark focuses on the price we pay for dividing ourselves up into camps based on a notion of religiosity that is, in his view, absurdly narrow.

Dark’s previous book, The Sacredness of Questioning Everything, seemed to be directed primarily toward younger Christian readers wondering how to protect faith from doubt. (His answer: you don’t have to and shouldn’t try. Doubt is faith’s necessary friend.) Life’s Too Short to Pretend You’re Not Religious, as the title implies, is aimed at a wider audience that includes the confirmed doubter, the person who easily and even with pleasure disavows any worship or faith practice. God and faith as such don’t get much play at all here. Instead, Dark focuses on the price we pay for dividing ourselves up into camps based on a notion of religiosity that is, in his view, absurdly narrow.

Dark argues for viewing religion as simply “a controlling story,” the narrative each of us creates to make sense of the world—or at least become reconciled to chaos. Religion is the meaning behind the choices we make, our guide to joy and our defense against sorrow. It provides a frame for our relationship to everything. In some sense, it is our relationship to everything. Defined this way, religion becomes something that “cuts to the core of what we’re really doing and believing, of what values—we all have them—lurk behind our words and actions.” This broadened concept of religion makes it impossible to differentiate between the people who have one and those who don’t. It becomes a means to stop seeing others as “participants in games we ourselves aren’t playing, as if they’re somehow weirdly and hopelessly enmeshed in cultures of which we’re always only detached observers.”

In Dark’s view, acknowledging this universality of religion does a lot more than knock down the snobbery and cultural labels that divide us. It spurs us toward self-questioning of a particularly honest and humble sort. We have to grapple with what we’re “really up to” and become aware of what’s going on in our minds, knowing that we are as gullible and vulnerable to error as the next guy. And this in turn opens us up to the possibility of deep engagement with our fellow humans, freed as we are from our fantasies of superiority and otherness. It renders judgment and debate over belief moot, and moreover, actually gives us something to talk about. “Putting religion on the table in this way, if we’re open to doing so, might be the most pressing, interesting, and wide-ranging conversation we can have,” he writes.

In Dark’s view, acknowledging this universality of religion does a lot more than knock down the snobbery and cultural labels that divide us. It spurs us toward self-questioning of a particularly honest and humble sort. We have to grapple with what we’re “really up to” and become aware of what’s going on in our minds, knowing that we are as gullible and vulnerable to error as the next guy. And this in turn opens us up to the possibility of deep engagement with our fellow humans, freed as we are from our fantasies of superiority and otherness. It renders judgment and debate over belief moot, and moreover, actually gives us something to talk about. “Putting religion on the table in this way, if we’re open to doing so, might be the most pressing, interesting, and wide-ranging conversation we can have,” he writes.

Connecting and sharing in this way is of critical importance in Dark’s personal religion. There’s no distance between communion and Communion in his particular Christ-guided way of seeing, and he declares that “the idea that any of us can have our meaning alone or be the sole authors of our own significance or have joy for which we have only ourselves to thank is a death-dealing delusion.” He lobbies instead for what he calls “the chother principle”—“chother” being a word born when his young son described embracing cartoon characters as “holding their ‘chother.” Holding to the chother principle means realizing that “our very sustenance and whatever identity we can be said to have comes to us via the fact of relatedness or not at all.” It’s a notion he calls “soul-savingly obvious but still countercultural,” and so it is in this narcissistic and self-congratulatory age.

Anyone familiar with Dark’s earlier work will recognize his rhetorical signature in Life’s Too Short: all manner of pop-culture references, from Saturday Night Live to Scooby-Doo; frequent nods to intellectual, literary, and spiritual influences, including Wendell Berry, Daniel Berrigan, and Thomas Merton; and enthusiastic endorsement of science fiction’s revelatory power. Dark’s commitment to embracing the world whole makes him the sort of writer who can say in all seriousness but with a twinkle in his eye, “I believe Radiohead.” It’s a style that might not please readers who think fast food should never share a table with haute cuisine, but such readers are not the ones Dark seems to have in mind. The book is above all an exhortation, albeit a carefully considered one, to do nothing less than be and see in a new way. For those willing to consider that task, it is, in the best sense, a first-rate sermon.

Maria Browning is a fifth-generation Tennessean who grew up in Erin and Nashville. A graduate of Mount Holyoke College, she has attended the Clothesline School of Writing in Chicago, the Moss Workshop with Richard Bausch at the University of Memphis, and the Sewanee Writers’ Conference. She lives in White Bluff.