A Sense of Place

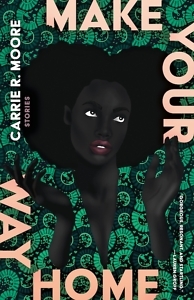

Carrie R. Moore’s debut story collection effortlessly holds simultaneous truths

Sometimes a debut shouts, insisting: “I’m new, I’m here, and I’m something to behold!” Other debuts enter the scene as if they’ve always been there, quietly confident and wondering what took y’all so long to see them. Carrie R. Moore’s debut, Make Your Way Home, is a collection of 11 stories so assured readers might be forgiven if they finish it and immediately start looking for the author’s earlier work.

Moore’s stories feel solid, substantial — each one thick with structure like a house well built. They are deeply researched and deeply rooted in both the American South and the Black experience there. Always, that experience is complicated, with every character fully aware of the ways home can be both a place you want to escape and a place you long to return to once you’ve left.

That idea shows up in the opening story, “When We Go, We Go Downstream.” Ever and Amari have been talking and messaging ever since he did some web design work for her years ago, and now Amari’s in Texas, his guest at his sister Leela’s wedding, hoping to see their long-distance relationship up close. Before that first message, though, Ever got to know Amari through her work as a journalist: “Her city had grown less familiar to her, she wrote, but she loved it still, like a troubled cousin sure to get himself together someday.”

The same could be true about the South, carrying as it does so much hurt and harm. In that way, it’s not unlike the family curse, set on Ever’s ancestor Elijah by his woman Evaline, “whom his master forbade him to call wife.” When Elijah escapes, leaving Evaline behind, the story goes that a heartbroken Evaline sought revenge from a witch, who set a curse on Elijah and his descendants, all of them doomed to failed relationships. The story of the curse has been half-believed and passed down, and now Ever shares the story with Amari — “Warily, the way his father told it to him.” Whether it is the curse or the unsettled feeling that rises when Leela’s bride is absent from the pre-wedding festivities, Ever is anxious: “Part of him fears that this weekend has started a countdown toward their inevitable end.”

Despite this collection’s confidence, the people who inhabit Moore’s stories are often afraid, like Brayden in the powerful “All Skin Is Clothing.” After a stray bullet lodges in the wall above the six-year-old Brayden’s bed, his Momma tells his father that the family has to move: “I don’t care if your mother did raise you in this house.” Even after they settle into their new neighborhood, Brayden remains mute and fearful: “He’d come so close to becoming the others. Boys who caught bullets in their spines. Who got jumped, their split ribs puncturing their lungs. Who went impossibly quiet after officers knelt on their necks. He searched for his own voice and found nothing.”

Despite this collection’s confidence, the people who inhabit Moore’s stories are often afraid, like Brayden in the powerful “All Skin Is Clothing.” After a stray bullet lodges in the wall above the six-year-old Brayden’s bed, his Momma tells his father that the family has to move: “I don’t care if your mother did raise you in this house.” Even after they settle into their new neighborhood, Brayden remains mute and fearful: “He’d come so close to becoming the others. Boys who caught bullets in their spines. Who got jumped, their split ribs puncturing their lungs. Who went impossibly quiet after officers knelt on their necks. He searched for his own voice and found nothing.”

This story demonstrates Moore’s considerable skill as it manages many issues at once: class, agency, loss, and our need for safety, shelter, and love. Instead of specifying when the story takes place, Moore shows the family unpacking VHS tapes. She doesn’t explain that Brayden’s parents operate within different social classes; instead, there is his working-class father’s question: “You really going to put them in public school? Go back to adjuncting?” And when Brayden’s older sister Cadence asks if she can go out “past eight, even, since this neighborhood was safer,” their father illustrates his complicated feelings about the place he comes from: “I don’t want you to think of things like that. Our old neighborhood — the people were still people, wanting different things.” He refuses to set himself apart from those people or that place. In the end, this story is less about fear and loss and more about love: the protective love Cadence feels for Braden, the first love she might be developing for their neighbor Nelson, the small gestures of committed love between their parents.

In “When We Go, We Go Downstream,” Ever realizes that choosing to love will always be a fearful and wonderful thing. The story closes with Leela and her bride at the altar and the officiant saying she’s never seen “a crowd so ready to bear witness.” Moore’s stories gather like that crowd, each of them full of joy and fear, each of them ready to bear witness to love. The stories in Make Your Way Home effortlessly hold simultaneous truths. They are both the past we wish to escape and the future that beckons. It may not be flashy, but Carrie R. Moore’s debut insists all the same: It is here and it is something to behold.

Sara Beth West is a librarian and a freelance writer focusing on book reviews and author interviews. In addition to Chapter 16, publications include Kirkus, Shelf Awareness, BookPage, Southern Review of Books, and more. She lives in Chattanooga.