A Sense of the Possible

Jane Hirshfield talks with Chapter 16 about poetry’s timelessness, camouflage in nature, and why she doesn’t need to be “pop-culture hip”

“Poetry’s engine is empathy,” writes Jane Hirshfield, “the ability to feel what others feel, in permeability rather than judgment.” This open-mindedness is apparent in both of her new publications: a poetry collection, The Beauty, and an essay collection, Ten Windows: How Great Poems Transform the World. While Hirshfield’s topics might be varied, an appreciation of art and artists always hovers close to the surface. It is rare to encounter an author who writes with such intelligence and generosity in equal parts.

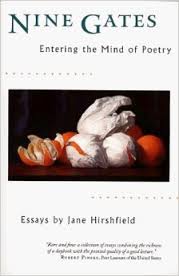

In addition to her eight poetry collections, Hirshfield is the author of a previous essay collection, Nine Gates: Entering the Mind of Poetry, and the co-translator of four books of poems. She currently serves as a chancellor of the Academy of American Poets. Prior to her upcoming Nashville appearance, Hirshfield answered questions from Chapter 16 via email:

In addition to her eight poetry collections, Hirshfield is the author of a previous essay collection, Nine Gates: Entering the Mind of Poetry, and the co-translator of four books of poems. She currently serves as a chancellor of the Academy of American Poets. Prior to her upcoming Nashville appearance, Hirshfield answered questions from Chapter 16 via email:

Chapter 16: In your new poetry collection, The Beauty, the poem “Anywhere You Look” ends with the unexpected line, “[W]hat war, they say.” Your poems seem timeless, but are you influenced by current events?

Hirshfield: What a small poem to awaken such a large question. Poetry as an art form lives in exactly that intersection. Poetry is a speaking to anyone, in any time, and it is also a speaking of this moment’s felt experience and newfound discovery. That’s why poems as old as The Iliad and The Odyssey keep their meaning and power to move a person living three millennia after their composition, even a person who has never experienced war directly. Good poems, I think, always carry this moment’s heart and mind, and “current events,” societal and personal both, are in some way also timeless. Poems by women writing in Japan in the ninth and eleventh centuries, read when I was nineteen years old, both reflected my own life back to me and changed it:

How invisibly

it changes color

in this world,

the flower

of the human heart.~Ono no Komachi, ninth century (from The Ink Dark Moon, co-translated by Jane Hirshfield and Mariko Aratani, Vintage Classics, 1990)

The poem talks about outer flowers’ visibility, and our human fickleness, which cannot be seen on the skin, in the color of the eyes. Anyone who has felt a lover’s abandonment can read this poem and know what it says. The poem also holds in its words Buddhist transience. I had never seen anything like this in poetry before, and went on, years later, both to study Buddhism further and to co-translate the poets.

I feel the fate of all who share this planet as my own fate. Poems by others are part of what taught me this. In the way of shared fate, I’ve written in response to 9/11, the Rwandan genocide, the Indonesian tsunami of 2004, Eastern Europe’s 1989 Velvet Revolutions, the Chilean dictator Pinochet, the first Gulf War. One early poem was written after reading in the morning paper of the now-forgotten American invasion of Grenada. The violence in Iraq, Afghanistan, now Syria, haunts my last three books.

But many, most, of my poems have no explicit reference to current events or to the recognizably hyper-modern world. Even the poems precipitated by them can be subtle in surface clues. I feel a certain expansion-joy if I write, say, a poem that includes by name a newly-discovered protein, or one that places a bullet train and a donkey in the same sentence. But I don’t think you need to include a bullet train to speak of our present-moment lives to our present-moment ears. I don’t need to be pop-culture hip. A mountain, a bird, a tree, carry this moment’s news. Sometimes my awareness of ecological fragility will be in a poem about them, sometimes it won’t. Poetry’s well goes down to an aquifer entirely boundless, connecting with every other waterway of existence.

But many, most, of my poems have no explicit reference to current events or to the recognizably hyper-modern world. Even the poems precipitated by them can be subtle in surface clues. I feel a certain expansion-joy if I write, say, a poem that includes by name a newly-discovered protein, or one that places a bullet train and a donkey in the same sentence. But I don’t think you need to include a bullet train to speak of our present-moment lives to our present-moment ears. I don’t need to be pop-culture hip. A mountain, a bird, a tree, carry this moment’s news. Sometimes my awareness of ecological fragility will be in a poem about them, sometimes it won’t. Poetry’s well goes down to an aquifer entirely boundless, connecting with every other waterway of existence.

Chapter 16: You recently confessed in an interview for All Things Considered that your memory is bad, but Ten Windows includes many lessons on history and language. What was your research process like for these essays?

Hirshfield: I’m grateful that I can look things up so easily now online. But I also have a good, deep library here in the house, a terrifically good hometown library, and a few things I do actually manage to remember. Each essay in Ten Windows began with a question. Finding a good question is a major part of these investigations into poetry’s deep underpinnings, for me. How that question was then explored was a combination of what I do have deeply enough seated that it just comes to mind when I’m thinking, what I actively set out to research, and what happened to come across my awareness during the months of thinking and writing. There’s a kind of reverse-treasure-hunt aspect: when you carry a good question around with you for a long time, it begins to magnetize answers. And then one sentence of thinking will draw the next sentence forward.

I also have a broad set of friends. Thought is often a dialogue, sometimes with books, sometimes with people. When I was writing about “Poetry and the Constellation of Surprise,” I contacted a researcher at Berkeley I’d met once and asked if he might talk with me about how neuroscientists understand surprise. When I was writing about hiddenness, I sent an email to quite a few biologist friends, requesting examples of strategies for hiding in the natural world. That chapter ended up with some things in it I’d never have come to without them. One astonishing camouflage: a kind of caterpillar that marches en masse in a way that makes them look like one large, not-to-be-messed-with snake.

I don’t think there is a single poem looked at in Ten Windows, though, that I did not know or search out on my own. All the poets included are on my shelves. I wouldn’t ever want to write about a poem that doesn’t awaken my own heart and psyche. These explorations aren’t dutiful. They were written for love of the art.

Chapter 16: The chapter “Poetry, Transformation, and the Column of Tears” includes the idea that “metaphoric powers are one reason people turn to poetry when they find themselves bewildered.” Are there special responsibilities involved in writing poems in response to a tragic event?

Hirshfield: I do think there are probably some ethics that come into play in poetry, especially in writing in public about the lives of others. These aren’t just a matter of ethics. They are equally strategies of writing that are simply effective. An unethical poem people will sidle away from without quite knowing why. But, first, while I don’t think this was meant by the question, I do want to say that I don’t believe any poem should be or ever is written because it is the responsible reaction to tragic events. The responsible response to tragic events is to come with food, blankets, tents, peacemakers, doctors, bridge engineers, political reform strategies, visas. The work of poetry, I’d say, is impractical, and works at a different speed. The lifesaving of poetry comes after the rope-and-ladder work. It’s a different level of life.

Hirshfield: I do think there are probably some ethics that come into play in poetry, especially in writing in public about the lives of others. These aren’t just a matter of ethics. They are equally strategies of writing that are simply effective. An unethical poem people will sidle away from without quite knowing why. But, first, while I don’t think this was meant by the question, I do want to say that I don’t believe any poem should be or ever is written because it is the responsible reaction to tragic events. The responsible response to tragic events is to come with food, blankets, tents, peacemakers, doctors, bridge engineers, political reform strategies, visas. The work of poetry, I’d say, is impractical, and works at a different speed. The lifesaving of poetry comes after the rope-and-ladder work. It’s a different level of life.

The ethical responsibilities of good poetry in writing about shared events? Here are a few to start with. Do not pretend to know what you cannot, or to have been where you were not. (Novels and plays and ethical poems are unmistakable as fictional constructs when they are fictional.) Do not over-assert or presume—poetry is not a force-fed sustenance; it is something offered. Do no harm. (Let us not forget that war chants are poetry, or that the Rwandan genocide began in part with slogan-chants played on the radio.)

I myself find metaphor useful in writing about the difficult in part because metaphor is so very tactful. It opens rather than narrows the range of the possible. That theme of enlarged possibility runs through the book: part of what poems do for us is increase the sense of the possible, the multiple. Poems invite subtlety and complexity and grant the permission to know that our lives are not arithmetic problems with single answers. Poetry’s engine is empathy: the ability to feel what others feel, in permeability rather than judgment. Poems of course do judge, have opinions, take stances. But the best ones leave room for another way of looking to stand with and inside and beside them. Poems make clear without making simple. They make large without making single.

Chapter 16: At times these essays seem concerned with what poetry shares with art more generally. Do you see the similarities between poetry and, say, painting or theater as a way to help a new audience read poems?

Hirshfield: When my first book of essays, Nine Gates: Entering the Mind of Poetry, had been out for a while, I began to hear stories: it had been taught to an architecture class, by a choreographer, by a composer. It was kept on the bedside tables of painters. This gladdened me. Art is art and works in art’s ways. That I had something to give to practitioners in other fields made me happy. I take so much from the other arts, and thinking about paintings, plays, pieces of music, are part of how I think about poems as well.

Chapter 16: What can we learn from studying the life of a figure like Bashō as opposed to what we learn by reading his work?

Hirshfield: The chapter in Ten Windows on Bashō does tell his life story but is much more the story of his relationship to haiku and how it works. It’s organized by the biography, but the poems are the point. Studying the lives of other writers as somehow exemplary or instructive can be perilous. We might think we should do what they did and we might find the same results. But each writer’s path is necessarily original to them. What we can learn from the lives of others is not so different from what we learn from the poems of others: suffering can be survived. Poems help us do that. Whatever human beings feel can be found in the lives of others, and conveyed to others still. Poems help us do that. Meanwhile, I love Bashō’s haiku, written to a student:

Hirshfield: The chapter in Ten Windows on Bashō does tell his life story but is much more the story of his relationship to haiku and how it works. It’s organized by the biography, but the poems are the point. Studying the lives of other writers as somehow exemplary or instructive can be perilous. We might think we should do what they did and we might find the same results. But each writer’s path is necessarily original to them. What we can learn from the lives of others is not so different from what we learn from the poems of others: suffering can be survived. Poems help us do that. Whatever human beings feel can be found in the lives of others, and conveyed to others still. Poems help us do that. Meanwhile, I love Bashō’s haiku, written to a student:

Don’t imitate me!

Don’t be the other half

of a melon.

(This is a different translation, more free than the one in the book—translating is never-ending….)

Chapter 16: How has co-translating Japanese poetry influenced your own writing?

Hirshfield: To answer that fully could be very long. I’ll say simply this: co-translating taught me to attend to language in ways both fiercely close and broadly open. And it taught me not to be afraid to experiment, to try things a different way. Japanese is very different from English, and translating Japanese requires that choices be made in English that are not ever made in the original poems: grammatical voice, verb tense, how to convey words that have double meanings. That spirit of freedom, trying things one way and then another, carried over to my revising of my own poems.

Chapter 16: In “Uncarryable Remainders: Poetry and Uncertainty,” you write, “To exchange certainty for praise of mystery and doubt is to step back from hubris and stand in the receptive, both vulnerable and exposed.” Is humility necessary for creating art?

Hirshfield: Well, if humility weren’t present before you started trying to write, it would certainly have to be present by the time you finished. But it probably helps a great deal if you begin with a spirit un-arrogant, with your hands, heart, tongue holding open the begging bowl that only the world and the muse and the language and all who have thought and wrote and painted before you can help you to fill. I don’t think I could write a poem out of feeling I knew something that needed to be said. I write poems because I sense there is something almost unsayable that might possibly be there to be found.

There’s a poem, though, in The Beauty, that speaks to the other side of this, which is equally true, “As a Hammer Speaks to a Nail.” Poetry is the realm in which equal truths don’t contradict. That poem begins,

When all else fails,

fail boldly,

fail with conviction,

as a hammer speaks to a nail,

or a lamp left on in daylight.

If a person would be reduced to silence by her or his own, very necessary, humility, then, well, a bit of cobbled together arrogance and courage might be just the thing. As with medicine, titrating the dosages matters. Humility is needed. Fearlessness and confidence are needed. Knowledge is needed. Not-knowing is needed. Are poems needed? The answer to that up is up to you.

[This article appeared originally on April 9, 2015.]

Erica Wright is the author of a new crime novel, The Red Chameleon, as well as two poetry collections. Now a senior editor at Guernica, she grew up in Wartrace, Tennessee, and received her M.F.A. from Columbia University.