A Southern Ramble

Reporter Dan Chapman retraces John Muir’s 1867 trek through the South

In September 1867, when John Muir was not yet 30, the future founder of the Sierra Club set off from Louisville on a long trek through Kentucky, Tennessee, North Carolina, Georgia, and Florida. His diary of the trip became A Thousand-Mile Walk to the Gulf, published in 1916 — two years after his death and half a century after the arduous journey it describes.

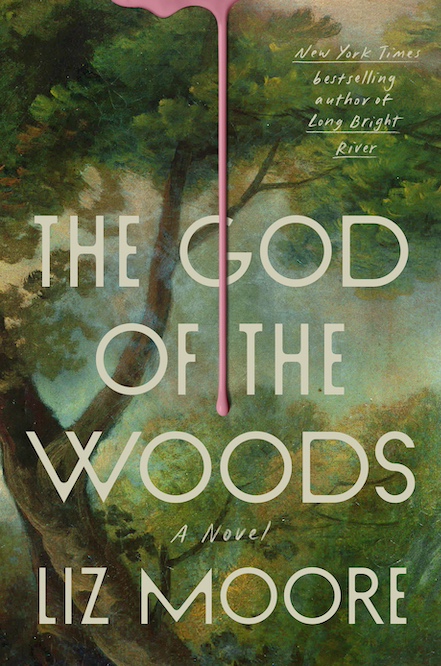

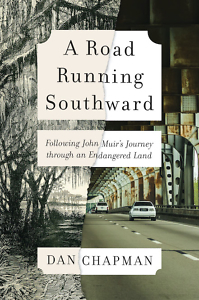

Dan Chapman, a Georgia-based environmental reporter, retraces Muir’s path on foot and by Subaru in A Road Running Southward: Following John Muir’s Journey through an Endangered Land. Over the course of several trips, he traces the 1867 walkabout as closely as he can, interviewing environmental experts along the way and, as did Muir, bearing witness to Southern nature under siege from development and pollution.

Dan Chapman, a Georgia-based environmental reporter, retraces Muir’s path on foot and by Subaru in A Road Running Southward: Following John Muir’s Journey through an Endangered Land. Over the course of several trips, he traces the 1867 walkabout as closely as he can, interviewing environmental experts along the way and, as did Muir, bearing witness to Southern nature under siege from development and pollution.

The book opens near the end of Muir’s journey, in Savannah’s Bonaventure cemetery, made famous by John Berendt’s Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil. While Muir camped there for three days in November and awaited a money order from his brother, the coastal fauna “invigorated Muir’s mind,” Chapman writes, “and made the twenty-nine-year-old wanderer reconsider long-held notions of life, death, nature, and man’s twisted relationship with all three.” After pointing out that other biographers consider the cemetery sojourn transformative to the man who would one day help establish Yosemite as national park, Chapman pockets a flashlight and flask of whiskey to camp among the tombstones and mosquitos.

“I take another sip of rye and channel my inner Muir,” Chapman writes, “but not in a creepy, séance-y way. I picture him, like me, staring vacantly skyward and thinking Big Thoughts.” But Chapman’s reverie is soon interrupted by fireworks in the distance, a ship’s foghorn, and rain. When he seeks a dry crypt, he is “freaked out” by an eerie running woman who turns out to be an oxidized bronze statue. And while the humid October night allows Chapman to reflect on the measurable and serious effects of global warming on low-lying Savannah, his mishaps set a comic tone that emerges throughout the book.

Chapman points out that rather than walk to Florida (“the poster child for nature gone bad”), when Muir’s money arrived he caught a steamer to Fernandina, north of Jacksonville, to continue hiking to the Gulf. “The abundance of invasive, weird, and biologically harmful plants and animals — eight-foot monitor lizards, Cuban tree frogs, wetlands-killing melaleuca trees, deer-swallowing Burmese pythons — keeps Carl Hiaasen in business,” Chapman notes of the state where Muir’s trek ended. His wry observations and self-deprecating wit make a book that delivers great doses of history and bad news surprisingly readable.

Chapman points out that rather than walk to Florida (“the poster child for nature gone bad”), when Muir’s money arrived he caught a steamer to Fernandina, north of Jacksonville, to continue hiking to the Gulf. “The abundance of invasive, weird, and biologically harmful plants and animals — eight-foot monitor lizards, Cuban tree frogs, wetlands-killing melaleuca trees, deer-swallowing Burmese pythons — keeps Carl Hiaasen in business,” Chapman notes of the state where Muir’s trek ended. His wry observations and self-deprecating wit make a book that delivers great doses of history and bad news surprisingly readable.

Other recent books have similarly roamed the South with an environmental angle, profiling experts along the way: Georgann Eubanks seeks out vanishing plant species in Saving the Wild South; Rob Simbek describes his favorite critters in The Southern Wildlife Watcher; and Tyler J. Kelley explores failing dams and levees in Holding Back the River (not to mention this reviewer mucking through Southern caves in Hidden Nature). What makes A Road Running Southward different in thematic approach is that Chapman writes through the lens of Muir’s single-minded immersion in nature and its preservation. This focus allows the book to follow a literal map, printed just before the first page, with chapters moving from Muir’s experiences to Chapman’s to the contemporary environmental problems of each location and the local experts fighting to correct them. Chapman’s observations glue these diverse elements together.

After the introduction and a brief Muir biography, Chapman sticks to the naturalist’s route from Kentucky southward, stepping onto the Big Four railroad trestle — now a pedestrian walkway — to cross the Ohio (“one of the nation’s most polluted waterways”) into Louisville. At Mammoth Cave, he meets a biologist who teaches him about endangered river mussels. (“The male is a sex machine capable of impregnating downstream females while stuck in the mud.”) While attending Muir Fest, in Kingston, Tennessee, to observe a celebratory release of 200,000 native sturgeon into the Tennessee River, Chapman recalls that the town is also the site of the infamous 2008 coal ash spill. (“So much for my feel-good story.”) And so on.

Chapman’s command of history is solid, his environmental reporting by turns sad and infuriating, and his characters met along the way invariably memorable. But it is his engaging prose that keeps readers on the path all the way to Cedar Key, Florida, where A Road Running Southward, like Muir’s long walk, fittingly ends.

Michael Ray Taylor lives in Arkadelphia, Arkansas, and is currently writing about the struggles of several grassroots environmental groups within Tennessee.