A Tennessee Christmas

My father wasn’t about to buy a tree

“We cut our own Christmas trees in East Tennessee.”

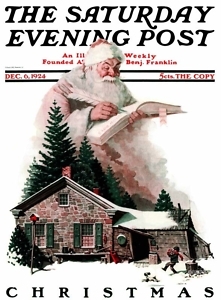

I once said that to someone and was told that it sounded as if I had grown up inside a Norman Rockwell painting. That’s a nice thought. Cutting one’s own Christmas tree certainly does evoke images of a happy family pulling a sleigh through snowy landscapes in the Appalachian Mountains. Clearly, there’s hot chocolate in the family’s future to warm the rosy cheeks of those exuberant children, while nostalgic parents look on with tilted heads and knowing smiles. Everybody wears plaid. It’s a snapshot of Americana, the kind we increasingly turn to in an effort to anchor ourselves to an illusion, one that tells us the world hasn’t gone completely barking mad.

I once said that to someone and was told that it sounded as if I had grown up inside a Norman Rockwell painting. That’s a nice thought. Cutting one’s own Christmas tree certainly does evoke images of a happy family pulling a sleigh through snowy landscapes in the Appalachian Mountains. Clearly, there’s hot chocolate in the family’s future to warm the rosy cheeks of those exuberant children, while nostalgic parents look on with tilted heads and knowing smiles. Everybody wears plaid. It’s a snapshot of Americana, the kind we increasingly turn to in an effort to anchor ourselves to an illusion, one that tells us the world hasn’t gone completely barking mad.

At the risk of shattering this illusion and unmooring our desire to escape reality through the medium of art, my family’s Christmas tree acquisition process wasn’t quite what Mr. Rockwell had in mind when he took brush to canvas. Our sleigh, for instance, was a 1974 Econoline van with green shag carpet and blue paneled walls. It had a sliding door, which proved convenient, and a skylight that proved not to be. It leaked. Happily, the horn worked. In regard to our attire, no one wore plaid because it was rarely sold at the flea market, which was held in the high school parking lot every Saturday morning. This is where my father typically acquired his complete wardrobe and ours as well when he could get away with it.

Lest I give the impression that we were poor, I should clarify that we were not. We may have been a long way from rich, but we lacked for nothing that we needed and for very few of the things that we just plain wanted (a fallout shelter and flame thrower, regrettably, being two of those things). The issue wasn’t poverty. The issue was that my father, son of a Great Depression survivor, had managed to elevate thrift to the level of a superpower and he was not afraid to wield it. Embarrassing statements and awkward social encounters also ranked high among his many talents, but thrift always reigned supreme, like an umbrella overarching a clutch of self-induced quirks the likes of which are rarely observed in a single person.

To my father, for example, a restaurant buffet was an opportunity to display his superpower. He saw in them a self-evident fiscal obligation to eat his fill right there on the spot, but also an opportunity to quartermaster his lunch menu for the remainder of the week. To him, all you can eat also meant all you can stuff into your children’s pockets and your wife’s purse. This is how I often came to find myself waiting for the Cedar Hill Elementary school bus in a less than fashionable jacket with grease-stained pockets that smelled of overcooked, heavily breaded, fried oysters from a restaurant called Edwards Seafood. Even at the tender age of 10, during the bicentennial year of our nation, I was already contemplating the social cost of being a smuggler’s mule and internally navigating the shifting moral frontier that separates thrift from theft.

So, when it came to obtaining our centerpiece of Yuletide cheer, my father wasn’t about to go buy a tree. To do so would be an affront to everything that he believed in. Yet a tree we must have, and to that end he conducted a reconnaissance, settled on a location, and formulated a plan to cut one down. Given my complete lack of experience in such things, it seemed perfectly reasonable to me that our acquisition process involved a five-paragraph operations order, a meticulous surveillance detection route, and an exhaustive list of contingency protocols.

“We wouldn’t want someone to follow us to our secret place,” my father said in the same hushed whispers that a resistance fighter might have used when coordinating a weapons cache in a Warsaw ghetto, circa 1939.

The plan, which evolved into a yearly event, went something like this:

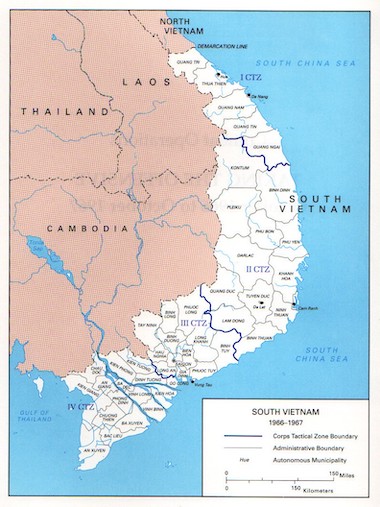

We boarded the 1974 Econoline van with green shag carpet and blue paneled walls and committed ourselves to a circuitous route as if pretending to go somewhere else. With our rearview mirrors reasonably free of suspicious vehicles, we’d continue our route out past an old guard shack that marked the edge of town. Back during World War II, when Oak Ridge was a secret city designed to facilitate the Manhattan Project, this was one of three secret entrances to the city.

Oh yes, the hills and valleys of East Tennessee are the perfect place to harbor secrets. Whether it happens to be moonshine still, a marijuana plot, or a place to build a device that ends a war like you really mean it, the hills and valleys of East Tennessee have a lot to offer when seclusion matters. In retrospect, it’s not surprising at all that it held a secret Christmas tree place just for us.

The entrance to our secret place was a nondescript dirt road, easily missed by the casual observer. We drove past it a few times, not daring to turn lest we be observed by other traffic on the main road. Our necks craned, our eyes squinted, and we milled about until finally the coast was clear and the timing was just right.

“Hold on.”

That’s what my father said just before careening off the main road and onto a dirt trail in a vehicle impressively unsuited for just such a task. At this point we were fully invested. The engine revved as we shot up the precarious slope. Tree limbs scraped the sides of the van. Bald, second-hand tires spun wildly as they struggled for purchase among gravely washouts. Two little heads, one of them mine, bounced off window and roof.

And then, suddenly, we were stopped.

Silence.

We were there.

I grabbed my surplus binoculars and assumed my appointed post 50 meters behind the shag carpet van. From here I could observe anyone encroaching upon our back trail from the base of the ridge. If I saw anyone approach, I was to return to the van with utmost haste. My sister, three years younger and now stationed at the driver’s seat, was tasked to honk the horn upon my command. My father would then return at the speed of a laser beam, and we would make an expeditious escape before anyone discovered our secret place.

At this juncture, noise discipline became paramount. “Never use an axe. Always use a saw. The axe makes too much noise,” my father, the consummate mentor, whispered before he disappeared into the forest.

What happened next played out the same way every year. There was always the familiar rustling of crisp leaves interspersed with brief periods of silence as my father presumably inspected potential trees. Then came the faint sound of a saw on wood … just two or three strokes followed by a listening silence. This was repeated a second time. At the end of that silence, a frantic sawing occurred, followed immediately by the distinctive sound of a falling tree and then something awkward being dragged through a pine thicket by a very large man.

That was my signal to abandon my post and collapse back upon the shag carpet van.

Everything went through the sliding door in a flurry of urgency: children, tree, brush saw … everything. Before we could even be strapped in again, we were barreling down mountain trails, leaving in our wake a rooster tail of wet leaves and muddy frost.

This became a yearly event until, sadly, one year it was not. Perhaps it had, like so many other things in life, simply succumbed to the tyranny of the urgent. Maybe we had grown too old for these forays or, quite feasibly, my mother had grown understandably weary of decorating unsymmetrical trees that boasted only a half dozen crooked limbs and the abandoned ruins of a squirrel nest. Whatever the reason, our trees from that point forward were of the parking lot genus, and they were obtained after a long and painful negotiating process between my father and a very unfortunate, exasperated vendor.

Years later, while home on leave from the Army, I was driving around in my Jeep entertaining hometown memories when I happened upon that place. I instinctively looked over my shoulder and felt a familiar sense of conspiracy. But what was this? The road was now improved and graveled and there was a sign. As I drew closer, the letters came into stark focus.

“Your Forest Your Future”

Tennessee Valley Authority

Reforestation Project

“Ah-ha,” thought I. “It all makes perfect sense now.”

As I drove away, I found myself grateful for childhood memories and, at the same time, quite appreciative for Tennessee’s statute of limitations as applicable to juvenile offenses — statutes that I necessarily reconfirmed just prior to writing this.

Copyright © 2021 by Anthony J. Rinderer. All rights reserved. Anthony J. Rinderer grew up in Oak Ridge. He joined the U.S. Army at 19 and became an attack helicopter pilot, serving in Somalia, Bosnia, Iraq, and Afghanistan. He’s a recipient of the Silver Star and Distinguished Flying Cross. He currently owns and operates Catamount Tactical LLC, based in Gloucester, Virginia, and works as a private military contractor and consultant. His poem “Awaiting Exfil” was recently published in The Deadly Writers Patrol, a veterans’ literary journal.