A Troubled King

Tavis Smiley talks with Chapter 16 about the final year of MLK’s life

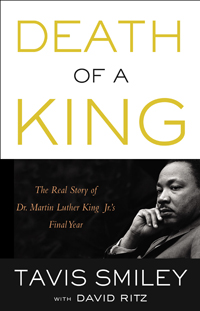

On Tuesday, April 4, 1967, Martin Luther King began his final year on Earth with a speech against American involvement in the war in Vietnam. It was a fitting start to an increasingly radical period in his life, according to Tavis Smiley, host of popular talk shows on public television and public radio. Smiley has collaborated with David Ritz, a noted co-author of autobiographies of music icons like Ray Charles and B.B. King, to write Death of a King: The Real Story of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s Final Year. Smiley and Ritz have produced a human portrait of King on a mission, one that often put him at odds with other civil-rights leaders of his day.

Prior to his appearance at The Booksellers at Laurelwood in Memphis on September 19, Smiley spoke with Chapter 16 by phone about King’s “darkest hours,” the way the civil-rights leader influenced Smiley’s own life, and what he thinks King would make of the current American landscape.

Prior to his appearance at The Booksellers at Laurelwood in Memphis on September 19, Smiley spoke with Chapter 16 by phone about King’s “darkest hours,” the way the civil-rights leader influenced Smiley’s own life, and what he thinks King would make of the current American landscape.

Chapter 16: What has the public forgotten about Dr. King that you wish to remind them about with this book?

Tavis Smiley: It’s not so much what they have forgotten—although some who were living during the King era have forgotten—but most have never known that, in the last year of his life, his truth was too subversive for some people. Everyone turned on him. For speaking his truth, he was ostracized; he was demonized; he was cast aside—by the White House, by the media, by white America, by black America. Sadly, by black America. He couldn’t get a book deal, couldn’t get a speech, and his organization was bankrupt.

Martin King started talking about what he called “the triple threat of racism, poverty, and militarism.” In the last year of his life, when he comes out against the war in Vietnam—and links the war and the money being wasted there to eradicating poverty in this country, to how that money ought to be spent—people didn’t want to hear that message. Everybody turned on him. The Martin King that I love best is the Martin King who stood up to all of that, kept telling his truth even as everything around him was crashing. He is no different in that regard than any other human being: we discover who we really are in our darkest hours. The darkest days of his life, the most controversial days of his life, happened to come in the last year of his life. So if you haven’t come to terms with who Martin King was in the last year of his life, I’ve got news for you: you don’t really know Martin.

Chapter 16: Of that “triple threat,” you write in the book that King repeatedly linked the war in in Vietnam to civil rights, despite the fact that many advisors in his own ranks were telling him not to. If he were alive today, do you think he would see a link between civil rights and our current “war on terror”?

Smiley: I think he would. Here is where African Americans in particular and progressives more broadly would have to come to terms with how to deal with Dr. King. If Dr. King were here right now, he’d be proud of the fact that Barack Obama, as a black man, is president. That would blow his mind, no doubt. The best parallel that we discuss in the book is that he went to Cleveland to campaign for Carl Stokes to be elected the first black mayor of a major American city. He worked really hard on that, so clearly King would have been involved in working to get Barack Obama elected as the first black president. I have no doubt about that.

But he also would have been unafraid, once Barack Obama was elected, to hold him accountable. On the issue of poverty, he’d be pressing Barack Obama. The president hasn’t done enough to fight poverty, and King would be pressing hard. Black folk and progressives would have to come to terms with how they processed a guy like Dr. King pressing Barack Obama as president. He would challenge the president on the use of drones. Barack Obama has used more drones that have led to the killing of more innocent women and children than George W. Bush did. Dr. King would be holding him accountable on the issue of poverty and on the issue of militarism.

On the issue of race, everybody acknowledges that, for all kinds of reasons, Barack Obama has stayed as far away from the race question as he could. Dr. King would not be afraid to take on the race question. On that triple threat—racism, poverty and militarism—he absolutely would have a critique of Barack Obama. But he would also have a critique of our society writ large on those three issues.

Chapter 16: In your acknowledgements, you thank an impressive list of people who knew Dr. King during his final year and who sat for interviews for the book. Did any of them say anything surprising or unexpected?

Smiley: I’ve been studying King since I was twelve years old, and most of what they said confirmed what I already knew. I needed to talk to the people around him for two reasons. First, to get my research independently confirmed. A lot of the people around him have written their own books over the years: Belafonte, Andy Young, Dorothy Cotton, Clarence Jones, Wyatt P. Walker, Garvin Taylor have all written their books. So some of it was just a matter of talking to them about the stuff they had written in their books to confirm my research.

Smiley: I’ve been studying King since I was twelve years old, and most of what they said confirmed what I already knew. I needed to talk to the people around him for two reasons. First, to get my research independently confirmed. A lot of the people around him have written their own books over the years: Belafonte, Andy Young, Dorothy Cotton, Clarence Jones, Wyatt P. Walker, Garvin Taylor have all written their books. So some of it was just a matter of talking to them about the stuff they had written in their books to confirm my research.

But the second and equally important reason that I talked to them is that the book is really a historical novel. It’s not a history book. I wanted it to read like a novel. Everything in it is true, but I wanted it to be like a screenplay, a page-turner that lets readers get sucked into the story. In order to write in a novelistic way, I had to talk to the folk who were around to get the context. Most of the content I already knew from my research. The context was what was lacking.

So when King is on an airplane, flying from New York to L.A. as he is in the first chapter, what is he thinking? What’s going through his head at that moment? When he’s in the car, listening to the radio, what kind of music does he play? When he goes to see Ike and Tina open for Sam and Dave at Madison Square Garden, what is he like backstage after the concert? When he went to “The Tonight Show” as a guest of Harry Belafonte, who was guest-hosting an episode for Johnny Carson, what was King like on the show? I could read the transcript of what he said, but I needed that texture. Talking to the folks around gave me the context that I needed to write this as a historical narrative. They helped me paint the picture of what he was like beyond what I read on the pages of what he said.

Chapter 16: This book, unlike a traditional history, certainly puts the reader inside the head of Dr. King. It renders scenes from his point of view.

Smiley: I take that compliment with great humility. That was the goal. You see from reading the book that I never refer to him as Dr. King—from page one to the end, he’s Doc. I wanted to put you in his inner circle. I wanted you to revel in his humanity. I wanted you to see his flaws. I wanted you to feel the joy, the pain, the disappointment, the despondency—I wanted you to be his friend. I wanted to put you in that inner circle with him. This is a story told from Doc’s perspective, not from a historian looking at his life. This is what he went through, and you are right in the space with them. That’s what I was trying to achieve.

Chapter 16: You mention in the introduction that your early success as a public speaker was in memorizing and reciting King speeches. Do those speeches stay with you today?

Smiley: Absolutely. Throughout high school, I did a different speech every year as a member of the speech team. The way the speech and debate season worked is you would start with a speech, and over the course of the season you would rehearse and perfect it. Hopefully by the time the season was over you could get to the state championships. You really worked on and honed this speech over the course of several months. So every year that I was in high school, I did a different King speech.

There are at least three or four of his speeches that I know pretty much verbatim, beginning to end, and I am amazed sometimes at the recall that I have for those speeches. Then again, I’m not so much amazed because I have been such a student of King since I was twelve. Everything I could get my hands on that had to do with King—I always wanted to read it, to watch it, to dissect it. Eventually I became able to talk to the folk around him on my TV and radio shows. I’ve just been so immersed in this Kingian adventure my whole life—that stuff just stays with you, man.

Chapter 16: You emphasize that King was first and foremost a Baptist minister, who tried to preach from a pulpit every Sunday. If you would indulge in a bit of speculation, how do you think King the minister would view the current struggle for gay rights and gay marriage?

Smiley: I think that Dr. King was ultimately about celebrating the humanity in each of us. Everything about his work and witness was about celebrating and reveling in the dignity and the humanity of all of God’s children. He said that in one way or another time and time again. I don’t want to speculate on what his personal view of gay marriage would be because I don’t know. But I do know that he would want to respect the dignity and the humanity of every child of God, as he would put it, and I have never seen anything on the record where King ever was for the shrinking of rights. His modus operandi was always about expanding rights, never shrinking them.

King tried to stay out of the lane of judging people. He knew that he was but a public servant, not a perfect servant. In the last year, as we detail in this book, we see many times, as a Baptist preacher on Sunday mornings at Ebenezer Church in Atlanta, where he is preaching sermons that are a bit confessional. He confesses things in his sermons about his own shortcomings. When he is despondent and depressed, he is trying to preach himself through his own despondency and depression. He knew that he was far from perfect. Let’s face it, he talked about his adultery. He knew that he had his own issues to deal with. I’m not trying to define how he would view gay marriage, but I am saying that he would try to stay out of the lane of judging people.

Chapter 16: And, in all probability, he would still be fighting that same triple threat he was fighting in 1967?

Smiley: No doubt about it. With all due respect, it’s not just ‘in all probability.’ It is a fact, and here is the point: in Ferguson, Missouri, for the last few weeks, what have we seen on display? Racism, poverty, and militarism. All three of those things on display in one city for the whole nation to see. Racism, poverty, and militarism. He would definitely be fighting those things.

Michael Ray Taylor teaches journalism at Henderson State University in Arkadelphia, Arkansas. He is the author of three traditional books of nonfiction—Cave Passages, Dark Life, and Caves—as well as The Cat Manual, an ebook.