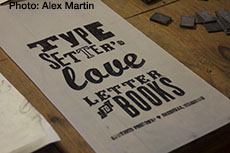

A Typesetter’s Love Letter to Books

Taking a love of the printed word to a new level

Every year my mother tries to buy me an e-reader for Christmas. It’ll save so much space in your apartment, she says; you’ll stop hurting your back when you lug around all those books, she says; it’s cheaper, she says. And every year I send her a long list of hardcover new releases and limited-edition classics I’d rather have instead.

A few weeks ago I moved into a different apartment. I try to pretend I’m not a materialist, but there’s one large exception to my minimalist fantasy: big, beautiful, stinky books. Books and all their lovely pages. Books I’ve scribbled notes in dating back to early high school. Books that, when piled together, weigh a ton.

A few weeks ago I moved into a different apartment. I try to pretend I’m not a materialist, but there’s one large exception to my minimalist fantasy: big, beautiful, stinky books. Books and all their lovely pages. Books I’ve scribbled notes in dating back to early high school. Books that, when piled together, weigh a ton.

During the move, I carried more than two hundred and fifty books up a flight of stairs. As I was packing, I quickly realized that my best tactic was to spread the books around, dispersing them into as many boxes as possible. Later, unpacking, I found surprises in my neatly organized boxes—a box with scarves, wool socks, winter sweaters, and the collected novels of Nathaniel Hawthorne. A box with dry goods: pastas, trail mix, Annie’s macaroni and cheese, de Tocqueville’s Democracy in America, breakfast bars, cake mix, and the Norton anthology of Shakespeare. A vintage suitcase with art materials, watercolor paper, oil paints, and Willa Cather.

In its current state, my new apartment contains little pockets of books that creep up in the strangest places—in the cabinets, above the piano, on the dining-room chairs, and anywhere else that might spare them from collecting too much dust until I can find a big enough book shelf.

It took me a long time to embrace my love for books as physical objects. I’ve always seen myself as the sort of person who appreciates the substance of a thing, from a book to a box of cereal, above all else. When it comes to my books, I take pride in my ability to close-read a Shakespearean sonnet, to produce essays on such obscure subjects as literary gastronomy in Henry Fielding’s Tom Jones. Even so, for me, few things compare to a new book with a clean, sleek cover design and some nice typography.

A friend once recounted to me a story about Frank Lloyd Wright’s Rosenbaum House in Alabama. When the city of Florence undertook its restoration, architects and builders found large portions of the house untouched, including the extensive Rosenbaum family library. When they opened the books, they found that termites had eaten away at the pages but avoided the printed words. As the restorers flipped through the books, thousands of miniature black letters spilled out onto the floor.

A friend once recounted to me a story about Frank Lloyd Wright’s Rosenbaum House in Alabama. When the city of Florence undertook its restoration, architects and builders found large portions of the house untouched, including the extensive Rosenbaum family library. When they opened the books, they found that termites had eaten away at the pages but avoided the printed words. As the restorers flipped through the books, thousands of miniature black letters spilled out onto the floor.

These are the sorts of things I think about when I hold a book.

It was my love of letters and physical books that led me to letterpress printing. On a whim, as I was preparing to move to Nashville, I applied to intern with Hatch Show Print. I figured I wouldn’t be able to get a full-time job right away, and interning would at least occupy my time.

By then most of my friends from high school and college were working salaried jobs or attending law school. I was far from home, but there were email chains and social-media groups keeping me in contact with everyone else. I didn’t contribute much to those threads because most days I felt like a failure among my peers—my most recent source of income had been scooping ice cream for minimum wage. When one of my old friends finally asked me what exactly I was doing in Nashville, I said I was working in a letterpress shop that specialized in nineteenth-century printing techniques. I left out the fact that I wasn’t being paid. Even so, at the moment, it sounded a whole lot better than toiling away at law school.

But this isn’t a narrative about how artistic expression overpowered graduate school and textbooks and office cubicles. It’s about the fact that I simply enjoy handling twelve-point metal type. I get a kick out of arranging tiny letters and running presses that are older than I am. Few things make me happier than doing hours of detailed work to create a product that technology is supposed to have deemed obsolete.

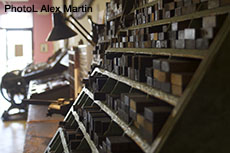

The thing about letterpress printing is that it is extremely monotonous. In order to produce a single poster or card, multiple rows of wood and metal letters must be carefully assembled on a press. Imagine if a Microsoft Word document took on a tangible three-dimensional state. Every letter is an object. To add another layer of confusion, every space between the words is also an object. And, like some sick literary jigsaw puzzle, all of these objects need to fit together in a neat, precise rectangle on the press. Preparing type to be printed takes at least three times as long as the actual process of printing itself. And this is how people formerly printed entire books.

The thing about letterpress printing is that it is extremely monotonous. In order to produce a single poster or card, multiple rows of wood and metal letters must be carefully assembled on a press. Imagine if a Microsoft Word document took on a tangible three-dimensional state. Every letter is an object. To add another layer of confusion, every space between the words is also an object. And, like some sick literary jigsaw puzzle, all of these objects need to fit together in a neat, precise rectangle on the press. Preparing type to be printed takes at least three times as long as the actual process of printing itself. And this is how people formerly printed entire books.

As my peers were climbing career ladders or obtaining advanced degrees, I dawdled around print shop after print shop, mastering a painstaking and outdated craft. Between setting type, proofing a poster, and actually getting everything on the press, it can take days or weeks before any kind of a tangible product—whether it’s a poster, a card, or a handbill—gets finished. The joy of it, for me, comes from the mindless feeling of doing something so scrupulous that it becomes completely absorbing.

The fact of the matter is that it has led me nowhere except this essay.

There’s a popular motto over at Hatch Show Print: “Preservation through production.” Before I get too metaphorical with it, the motto has a technical explanation. When pieces of wood and metal type go unused, they deteriorate more quickly. The type builds up dirt and grime from sitting in old cases, and the individual wood pieces begin to crack when any pressure is placed on them. The unused type pieces become incompatible with their more worn-down counterparts and eventually stop being used at all. It seems counterintuitive to say that being gentle with the artifacts of letterpress printing is the best way to destroy them, but so it goes—produce and preserve.

When I first moved to Nashville, I lived in a pool house located in the backyard of a very generous family friend. I never unpacked my books while I was there— even after driving all two hundred and fifty of them twelve hours from my hometown of Washington, DC. My mother insisted that I leave them at home, buy that e-reader, save space, etc. I, of course, insisted on the books. They traveled from temporary home to temporary home while I traveled from temporary part-time job to temporary part-time job. I refused to unpack the books until I could place them on a proper shelf in a home of my own. It wasn’t worth the trouble to unpack the books, I thought, if I wasn’t going to stay.

This determination mostly left me feeling more disoriented. I would sit in my makeshift homes and long for the comfort of a familiar book, flipping through its pages, discovering old notes I had left myself in the margins, and finding my favorite passages. As I fished individual books out of their cardboard boxes, I had to resist the urge to pluck out five more complementary texts to go along with them—what good is reading Emily St. John Mandel’s Station Eleven if I can’t cross-reference it with my copy of King Lear? What if I want to compare it to McCarthy’s The Road? The spaces I inhabit have always been defined by a wall of books—from my childhood bedroom to the old college library that I might as well have lived in for four years. There’s a certain comfort in being able to stare at a neat row of book spines and have a visual diagram for a lifetime of reading.

This determination mostly left me feeling more disoriented. I would sit in my makeshift homes and long for the comfort of a familiar book, flipping through its pages, discovering old notes I had left myself in the margins, and finding my favorite passages. As I fished individual books out of their cardboard boxes, I had to resist the urge to pluck out five more complementary texts to go along with them—what good is reading Emily St. John Mandel’s Station Eleven if I can’t cross-reference it with my copy of King Lear? What if I want to compare it to McCarthy’s The Road? The spaces I inhabit have always been defined by a wall of books—from my childhood bedroom to the old college library that I might as well have lived in for four years. There’s a certain comfort in being able to stare at a neat row of book spines and have a visual diagram for a lifetime of reading.

My books are home now, though I continue to meander. I often find myself coming home to my apartment with its piles of books and reorganizing them—by theme, by date, even by color. It’s in these repetitive, fruitless tasks that I find my own sense of stability. Yes, I could buy an e-reader, and yes, I could design a poster on my computer. It wouldn’t take so much time and I’m sure my back would thank me for it. But the ritual of caring for objects that I love has trumped convenience for me. For, though I meander and change, these tasks remain permanent. And as long as the words and the rituals remain immutable, I’ll always find security in them.

[All photos shot by Alex Martin at Sawtooth Printshop in Nashville.]

Lindsay Lynch is a freelance writer and illustrator working in Nashville. She dreams of someday seeing her name printed in thirty-six-point Futura bold. When not scribbling down ideas, she can be found behind the counter at Parnassus Books.