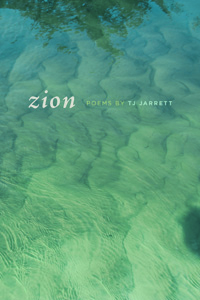

A Vision of Redemption

In Zion, poet TJ Jarrett explores the fierce possibilities of love and forgiveness

In a recent interview at The Atlantic, Nashville poet TJ Jarrett had some fascinating things to say about the parallels between her writing and her work as a software designer. But perhaps her most interesting comments came in response to a question about the spirituality in her poems. “I believe in redemption,” she said. “I believe some poems are really prayer.” Those beliefs are clearly evident in Jarrett’s remarkable second collection, Zion. These poems are shaped by a passionate desire to summon mercy and forgiveness in the face of terrible wrong, and they celebrate, without a trace of sentimentality, the sustaining power of love.

There are multiple delicate narrative threads running through Zion involving the death of Jarrett’s grandmother and events in Meridian, Mississippi, which was a notable battleground in the struggle for civil rights. Theodore Bilbo (1877-1947), a Mississippi politician who was famous in his day for a particularly flamboyant brand of white-supremacist demagoguery, appears in a series of poems as a sort of embodied spirit of American racism. He engages in an oblique dialogue with a nameless “I” who, we are led to infer, is black and female.

There are multiple delicate narrative threads running through Zion involving the death of Jarrett’s grandmother and events in Meridian, Mississippi, which was a notable battleground in the struggle for civil rights. Theodore Bilbo (1877-1947), a Mississippi politician who was famous in his day for a particularly flamboyant brand of white-supremacist demagoguery, appears in a series of poems as a sort of embodied spirit of American racism. He engages in an oblique dialogue with a nameless “I” who, we are led to infer, is black and female.

It would be a disservice to Zion to say that race is one of its chief concerns, if saying so gives the impression that this collection aspires to be social commentary, or that it is primarily focused on the personal wounds which racism inflicts. Jarrett’s poems are doing a different, deeper sort of work. They do engage personal suffering, and many of them are about race—unquestionably and overtly so—but they are also about everything that transcends our individual lives, our easy categories and reflexive responses. They present a spiritual or existential inquiry into the primal challenges to our humanity.

This inquiry is especially acute and daring in the Bilbo poems, which depict a relationship between victimizer and victimized that is freighted not only with history but also with what can only be called love. There’s a kind of moral passion at work between the two protagonists; the desire to be forgiven is met with an equally powerful, though conflicted, desire to forgive. In “Theodore Bilbo and I Begin Our Crossing,” the initial journey toward reconciliation is indistinguishable from exile:

We rowed farther and farther out

We rowed farther and farther out

Onto that river when a great fog

Descended upon us so that we could see

Neither the shore we left nor the shore ahead

The absolution that ultimately occurs in “Theodore Bilbo and I at Last Turn Face to Face” is a revelation to the giver, as well as to the recipient:

But there is this:

once there was me and there was you

and from my mouth like a shock of doves

comes forgiveness. Believe me,

I am as surprised as anyone.

The Meridian poems meditate more explicitly on the injuries of the past, and they contain an element of personal nostalgia, but like the Bilbo poems they approach memory obliquely and, often, through metaphor. In “Meridian, Last Night,” memory is a “house still standing and in ruin. / As it always was. As always.” The resolution found in the Bilbo poems, however, is more elusive here:

The past is both retribution and reward

Now that it has been endured.

And it is right that we stand in its ruin,

Among all this longing and decay.

Seeming to stand apart from the Bilbo and Meridian poems, and yet delivered in the same uncompromising voice, are deeply personal poems about love. Jarrett conveys the ferocious bond between mother and daughter in “1973: My Mother Cleaves Herself in Two”: “She will split / herself in two, shear the thorax, cast off the shell of herself / and consume what-she-was as afterbirth so that she may live.” The bittersweet aftermath of romantic love gets wry treatment in “Everything Men Know About Women”:

My mouth

grows heavy with all the things left unsaid

between friends, so I say: I am very happy

to fill the silence.

Jarrett has a deft but forceful style that combines with potent subject matter to create poems of great intensity. She makes masterful and subtle use of imagery, but the power of these poems lies more in her gift for conveying directly some of the most elusive truths of the human heart. Many of these poems are like flashes of lightning, offering sudden, violent illumination of the kind of dangerous feelings that often go unexpressed and unacknowledged. The collection as a whole captures something essential about the human ability to seek love in defiance of hate and grievous injury. Jarrett’s vision for our redemption is as fierce and hard-edged as our history is brutal, and it is a stunning thing to encounter.

Maria Browning is a fifth-generation Tennessean who grew up in Erin and Nashville. A graduate of Mount Holyoke College, she has attended the Clothesline School of Writing in Chicago, the Moss Workshop with Richard Bausch at the University of Memphis, and the Sewanee Writers’ Conference. She lives in White Bluff.