Floating Prison or Tropical Paradise?

In Islandology, Marc Shell explores the dynamic history of lands surrounded by water

If the title of Marc Shell’s 2014 book, Islandology, sounds like a Kenny Chesney album, its subtitle—”Geography, Rhetoric, Politics”—immediately sets the record straight. The islands Shell studies are less likely to be tropical playgrounds than Scandinavian ice-lands where tribes wage internecine battles for fishing sovereignty.

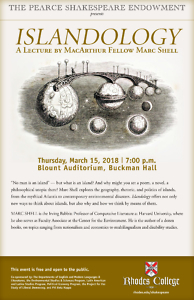

An endowed professor of comparative literature at Harvard, Shell brings an extraordinarily broad and diverse scholarly background to bear on every topic he explores. The books he wrote during the 1970s and ’80s, which earned him a MacArthur “genius” fellowship, combine literary theory with economics, psychology, philosophy, and anthropology to provide fresh insights into socially vexed questions. In The End of Kinship, for example, Shell argues that literary commentary “can offer unique access” to the thorniest subjects, including incest.

Shell believes that literature reveals profound truths through intuition, as an extension of experience. In Islandology, he uses Shakespeare’s Hamlet as the key to unlocking the lessons that are hidden in the ways nations describe their homelands and borders.

Prince Hamlet feels isolated on Elsinore, detached from his college friends in Wittenberg and separated from the scenes of his father’s triumphs. In his isolation he calls Denmark a “prison.” To his uncle Claudius, the new king, Denmark is a connected and powerful state that can readily extend its military might to other nations. Shell draws attention to the parallels with England, an island monarchy sitting on the crown of Europe—his crafty way of framing the central issue of Britain’s foreign policy from Shakespeare’s age to the era of Brexit.

For Shell there are significant political ramifications to the way we conceptualize islands. The transition of ancient Athens from part of the mainland to an island city-state—a change accomplished by earthworks—was crucial to establishing Athenian political self-consciousness. “Whatever one calls a particular island,” Shell writes, “often becomes a linguistic ‘password’ used to identify you as a member of one cultural group as against another.”

Though less personal than Shell’s books on stuttering and polio, Islandology allows readers access to the roving quality of his thinking. His primary mode of operation is the tangent, following strands of thought and drawing upon an endless trove of learning until suddenly the whole picture snaps into focus. A discussion of “island cities,” such as his own native Montreal, leads him to the lighthouse on the Greek island Pharos, the Rialto of Venice, an Iranian film set in the Persian Gulf, seventeenth-century Dutch travel writing, and Korean ice-breaking ships. The pattern he finds: these islands continually struggle between an instinct to isolate from the world’s unrest and a desire for economic expansion. The tension never abates.

Though less personal than Shell’s books on stuttering and polio, Islandology allows readers access to the roving quality of his thinking. His primary mode of operation is the tangent, following strands of thought and drawing upon an endless trove of learning until suddenly the whole picture snaps into focus. A discussion of “island cities,” such as his own native Montreal, leads him to the lighthouse on the Greek island Pharos, the Rialto of Venice, an Iranian film set in the Persian Gulf, seventeenth-century Dutch travel writing, and Korean ice-breaking ships. The pattern he finds: these islands continually struggle between an instinct to isolate from the world’s unrest and a desire for economic expansion. The tension never abates.

For all his erudition, Shell treats popular entertainment, especially movies, with the same critical scrutiny he gives to ancient philosophy. He uses islandology as a way of generating new interpretations of films as various as Ingmar Bergman’s Scenes From a Marriage and Laurel and Hardy’s Atoll K, noting how both use islands as microcosms for perennial conflicts.

The value of Shell’s work lies in its capacity to alter our perspectives. In Islandology he takes the simplest questions of definition—what is an island?—and demonstrates that how we answer that question reveals who we are.

Sean Kinch grew up in Austin and attended Stanford. He earned a Ph.D. from the University of Texas. He now teaches at Montgomery Bell Academy in Nashville.