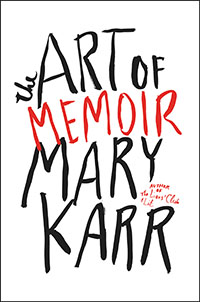

Advice from a True Believer

Mary Karr celebrates the examined life in The Art of Memoir

Mary Karr wants to make one thing very, very clear in The Art of Memoir: it is not acceptable to pass fiction off as fact—not even a little bit, not ever. Though there’s a growing acceptance these days of memoirists indulging in undeclared fictionalizing for the sake of art or emotional truth, Karr is having none of it and likens the practice to a deli’s putting “just a teaspoon of catshit” in your sandwich. The writer who makes stuff up without admitting it doesn’t just betray the reader, she argues. He cheats himself by “missing the personal liberation that comes from the examined life.”

The notion that writing about your own life is a path to liberation, perhaps even salvation, runs throughout The Art of Memoir. Karr is a true believer in the transformative power of the form. She’s also, of course, one of its contemporary masters. Her three memoirs—The Liar’s Club, Cherry, and Lit—have all been bestsellers and received abundant critical praise. (The difficult-to-please Michiko Kakutani of The New York Times described The Liar’s Club as “astonishing.”) Karr is a highly regarded teacher, as well, and The Art of Memoir is both a celebration of memoir’s literary value and a short course in its pitfalls and challenges.

The notion that writing about your own life is a path to liberation, perhaps even salvation, runs throughout The Art of Memoir. Karr is a true believer in the transformative power of the form. She’s also, of course, one of its contemporary masters. Her three memoirs—The Liar’s Club, Cherry, and Lit—have all been bestsellers and received abundant critical praise. (The difficult-to-please Michiko Kakutani of The New York Times described The Liar’s Club as “astonishing.”) Karr is a highly regarded teacher, as well, and The Art of Memoir is both a celebration of memoir’s literary value and a short course in its pitfalls and challenges.

The little matter of accuracy is certainly one of its primary challenges, and Karr devotes a good portion of this book to the question of just what constitutes truth in memoir. Shunning outright deception is simple enough, but as anyone who has tried to interrogate her own early memories knows, the past is murky territory, and documentary evidence, if it even exists, is often not as definitive as we want it to be. Getting reliable confirmation from others isn’t always easy, either. Karr describes a classroom exercise in which she stages an argument with one of her colleagues. The incident is recorded on video, and the students are asked to write their own independent accounts. They almost invariably get it wrong, even to the point of misidentifying which party was the aggressor. “My unscientific, decades-long study,” writes Karr, “proves even the best minds warp and blur what they see.”

Karr explores various strategies memoirists take to compensate for their own blurred recall, from sharing drafts with family and friends for their perspectives (something she invariably does) to throwing up warning signs to readers that a recollection is uncertain, wishful, or hyperbolic. Artful forms of such flagging can be an essential part of a memoir’s distinctive style, according to Karr, who cites the opening of Harry Crews’s A Childhood as a vivid example. In it, Crews declares his first memory “is of a time before I was born”—a clear indicator to his reader, says Karr, that “he embraces gossip and hearsay and all manner of apocrypha.” Crews also uses plenty of what Karr calls “amplification,” like claiming that his skin and fingernails actually “came off like a wet glove” after his arm was scalded. The gruesome image can’t be literally true, but the exaggeration is acceptable because Crews has already alerted us that “his path vis-à-vis external veracity or reporting history is as undulating as a snake’s.”

Karr explores various strategies memoirists take to compensate for their own blurred recall, from sharing drafts with family and friends for their perspectives (something she invariably does) to throwing up warning signs to readers that a recollection is uncertain, wishful, or hyperbolic. Artful forms of such flagging can be an essential part of a memoir’s distinctive style, according to Karr, who cites the opening of Harry Crews’s A Childhood as a vivid example. In it, Crews declares his first memory “is of a time before I was born”—a clear indicator to his reader, says Karr, that “he embraces gossip and hearsay and all manner of apocrypha.” Crews also uses plenty of what Karr calls “amplification,” like claiming that his skin and fingernails actually “came off like a wet glove” after his arm was scalded. The gruesome image can’t be literally true, but the exaggeration is acceptable because Crews has already alerted us that “his path vis-à-vis external veracity or reporting history is as undulating as a snake’s.”

But wrangling with the problem of truth is not, in Karr’s view, the memoirist’s primary task. “Every great memoir lives or dies based 100 percent on voice,” she says, and the search for an authentic voice can cost a writer years of work. She concedes that it’s ultimately a matter of craft but insists it cannot be dictated by ego or an infatuation with someone else’s work. The key to determining voice “grows from a writer’s finding a tractor beam of inner truth about psychological conflicts to shine the way.” An inauthentic voice, one not coherent with the writer’s own character and concerns, won’t carry the necessary power to engage a reader, no matter how skillfully it is delivered. Ambitious beginners are prone to reach absurdly far beyond themselves, with dismal results. “Nabakov wannabes don’t sound just like turds,” says Karr, “but like pretentious turds.”

And speaking of Nabokov, he’s a member of Karr’s personal pantheon of master memoirists and is celebrated at some length in this book, along with Crews, Richard Wright, Maya Angelou, Maxine Hong Kingston, and Michael Herr. Karr also devotes a short chapter to defending Kathryn Harrison, whose 1997 memoir of incest, The Kiss, was dismissed by some critics as a distasteful attempt to gain money and publicity. Karr argues that Harrison was pursuing the essential work of any memoirist, albeit with more extreme material than most. She is, says Karr, “a study in the courage a book can demand from its scribbler.”

In an age of memoirs as hot commodities, when it’s easy to dismiss the whole enterprise as cynical or narcissistic—or both—Karr’s fierce insistence on the memoirist’s courage is bracing. The work she describes in The Art of Memoir is not for weaklings, but she makes a convincing case that it is eminently worth doing.

Maria Browning is a fifth-generation Tennessean who grew up in Erin and Nashville. A graduate of Mount Holyoke College, she has attended the Clothesline School of Writing in Chicago, the Moss Workshop with Richard Bausch at the University of Memphis, and the Sewanee Writers’ Conference. She lives in White Bluff.