Against Stereotype

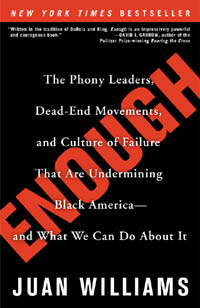

Award-winning journalist, author, and commentator Juan Williams talks with Chapter 16 about the state of civil rights in America

As a commentator for Fox News and National Public Radio, Juan Williams is a lightning rod for both the right and the left. An outspoken critic of certain black leaders, including Jesse Jackson and Al Sharpton, Williams is also an ardent, but not uncritical, supporter of the Obama administration. His sixth book, Enough: The Phony Leaders, Dead-End Movements, and Culture of Failure That Are Undermining Black America—and What We Can Do About It, explores the disconnect between the decisive victories of the civil-rights movement and the ground-level state of affairs for black Americans, who continue to live, he says, “as if they were locked out from all America has to offer.” On February 13, Williams will be at the main branch of the Nashville Public Library to moderate “A New Dialogue in Civil Rights,” a panel discussion which includes Rev. James Lawson, Betty Flores, and Daniel Losen. The event commemorates the fifty-year anniversary of Nashville’s student-led demonstrations and sit-ins.

Chapter 16: African American intellectuals and commentators tend to be criticized—Bill Cosby comes to mind—when they focus, as you do, on inner-directed issues of apathy and responsibility rather than outwardly directed attacks on institutionalized racism. How do you respond?

Williams: The critical point here is How do we advance the race? How do we advance our families? Everybody knows that the status of African Americans has improved radically, but for the longest time there was a fear that if you said things are getting better on the race front, white people or the government or the foundations would say, Ah, we’ve done enough, now it’s time to move on. [But] there’s no getting away from it—there’s a black president; two secretaries of state were black; you see black people running corporations. There’s something going on here, and failure to acknowledge it is failure to acknowledge reality.

Williams: The critical point here is How do we advance the race? How do we advance our families? Everybody knows that the status of African Americans has improved radically, but for the longest time there was a fear that if you said things are getting better on the race front, white people or the government or the foundations would say, Ah, we’ve done enough, now it’s time to move on. [But] there’s no getting away from it—there’s a black president; two secretaries of state were black; you see black people running corporations. There’s something going on here, and failure to acknowledge it is failure to acknowledge reality.

Chapter 16: Your fellow panelists—Betty Flores and James Lawson, specifically—are involved in immigration issues. Do you anticipate any friction between your focus on self and community-actualization and their concerns, which still seem very tied to institutional reform?

Williams: We have to have some kind of immigration reform; that’s an institutional issue in this country to deal with the large numbers of people who are here in this country illegally. I wouldn’t argue with them on that point.

Chapter 16: Would you make a distinction, then, between racism as currently experienced in the African American community and the global struggle against slavery, anti-Semitism, apartheid, and other forms of discrimination?

Williams: I am a huge supporter of people who are dealing with institutional racism, structural racism. These things are an abomination. There’s no sense of tension here unless people are denying reality. The way you pose the question, it’s either/or; I don’t see it in those terms. The kind of paralyzing, corrupting force that racism has been throughout so much of American history has been tremendously diminished, and that’s all I’m trying to say. Now it’s time to focus on what you and your children can do for yourselves, or what your community can do for itself, instead of pointing at those institutional forces with the same emphasis. But if you were in a place where there’s slavery or anti-Semitism, then of course you would want to battle them.

Chapter 16: You advocate that African American youth finish high school, get a job, and postpone marriage and childbearing until at least age twenty-one. For young people who aren’t growing up with such expectations, do you have any recommendations—for them, or for schools and the community—to help make these choices easier?

Williams: You’re asking me to rethink those messages in terms of kids who are not hearing them. There are adults around every child, but let’s say there’s no bonded relationship where a child feels there’s this strong, positive person who’s protecting and providing for them. Then you would hope that the shelter, the school, the foster-care family, somebody who’s in authority in the child’s life can say, I believe you can do it, but you’ve got to do your part, and your part begins with doing well in school. Having high expectations for young people is the first step.

Chapter 16: What is your most profound satisfaction with the first year of the Obama administration?

Chapter 16: What is your most profound satisfaction with the first year of the Obama administration?

Williams: I think he’s been a wise manager of the economy. I don’t think there’s much debate left and right, in terms of the economists, that without the bailout [and] stimulus spending we would have been in a depression. I know his critics on the right are in a fury over the deficit and the spending, but I think that’s a political attack. Given the nature of our interview, I think it’s important to say, too, that the example of Barack Obama as a family man and an educated achiever has been so important, not only for the black community but for this country. I think he’s an attractive person, and he helps shift some of the stereotypes about black men and about black people in general.

Chapter 16: And your most profound disappointment?

Williams: There’s so many. How do I start? The thing with health care has been a disappointment to me. I guess it’s because I’m rooting for him to succeed, but to see him somehow lose track of public opinion like that. He made promises to be transparent and to keep the American people informed about what he was trying to do. Instead they got all caught up in the process and about who’s voting how and what deal can we make with this person to get their vote in Congress, and it seemed like there was some kind of insider corruption taking place rather than a really necessary effort to fix the health care system. He should be the guy in the white hat here, but somehow he’s become the bad guy.

Chapter 16: You’ve been critical of Michelle Obama’s use of the First Lady’s pulpit, even going so far as to compare her to black nationalist Stokely Carmichael. If you were one of her advisors, what recommendations would you make?

Williams: I think they’re doing a fine job now. The comment I made was to the effect that if she is someone who’s out there making racial comments or talking about race, then she can’t be Stokely Carmichael in a designer dress. She can’t be someone who is an angry face of black America. You have to understand the role of the First Lady and how she is understood by Americans. They want someone who’s not a partisan in the political fray. Let her husband do that—that’s the path [he’s] chosen.

Chapter 16: You get flack from liberals for appearing on Fox News. Likewise, you’re criticized by conservatives for your comments on NPR. What is your role in keeping both networks “fair and balanced”?

Williams: If I said anything on NPR that was different than what I said on Fox or anything different on Fox than I said on NPR, I’d get a deluge of criticism. So I make a concerted effort to be the same person and do the job. What is really terrific is that both audiences like me; both audiences see value in what I have to say. Even when they disagree—and people disagree with me often—they’ll say I don’t think he’s spinning me. I think he’s a journalist trying to do his job, and offering me what he thinks. He may be wrong, but I wanted to hear what he had to say.

Chapter 16: The program at Nashville Public Library is called “A New Dialogue in Civil Rights.” In the new decade, what do you think are the essential components of this new dialogue?

Williams: The big thing going on in American society right now is the tremendous change in the population. We’re going from a population that was so heavily white to one that is now going to be a mix of people. And of course you throw in the idea that we are now part of a global economic and social structure—people going overseas for jobs, people coming here for an education; these sorts of things. I think we’ll look back on the twentieth century as a time when America could be a beacon to the world. In the twenty-first century it’s much more about allowing people to understand what it means to mix it up: to have a president who’s black, a president who’s a woman, a president who’s Hispanic or disabled—just different.

In the United States, we’re going to try and maintain this idea that everybody here has a chance to succeed. The big obstacle to that may not be what we are accustomed to, which was race and gender. The big obstacle in the twenty-first century may be class. Who has access to an education? Who has access to the job market or the capital market? People who don’t have access to those things are going to fall to the bottom of the social structure. It could be that we start to become calcified in terms of social movement that we don’t see as many people from the ranks of the poor moving up. That will be the challenge we face and the conversation we have to have in the twenty-first century.

On February 13 at 1 p.m., Juan Williams will be at the main branch of the Nashville Public Library to moderate “A New Dialogue in Civil Rights,” a panel discussion which includes Rev. James Lawson, Betty Flores, and Daniel Losen.