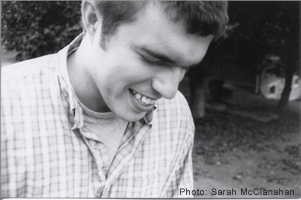

Against the Appalachian Minstrel Show

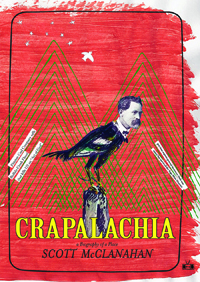

Scott McClanahan’s Crapalachia is not like any other mountain memoir you’ve read

In the received narrative, Appalachia is a hardscrabble place, but it’s also a place full of capital-C characters. Scott McClanahan, having left West Virginia and returned, knows this story well—as well he knows what his roots have granted him. A sharp self-awareness textures Crapalachia: A Biography of a Place, a surprisingly poignant work that manages to borrow from the Appalachian storytelling tradition as it confronts, even dismisses, its tropes and trappings.

Crapalachia is a story about place that can be told in this distinctive way only by One Who Got Away. On the one hand, it’s an homage to the people McClanahan has known and loved, and to the place and circumstances—to a great extent, the poverty—that shaped them. On the other, it’s a commentary on the fictive quality of all such biographical projects. In the book’s intriguing Appendix, McClanahan writes, “This book should not be thought of or included in a genre of literature called the Appalachian Minstrel Show,” and then proceeds to list just a few of the authors he’d shelve in that genre.

Crapalachia is a story about place that can be told in this distinctive way only by One Who Got Away. On the one hand, it’s an homage to the people McClanahan has known and loved, and to the place and circumstances—to a great extent, the poverty—that shaped them. On the other, it’s a commentary on the fictive quality of all such biographical projects. In the book’s intriguing Appendix, McClanahan writes, “This book should not be thought of or included in a genre of literature called the Appalachian Minstrel Show,” and then proceeds to list just a few of the authors he’d shelve in that genre.

McClanahan is delightfully cutting in his awareness of inequity (“A poor person means either their skin was dark or their accents were thick”) and unflinching in his confrontation of death, which is the Big Theme of this book in an overt way. In one tale, his Grandma Ruby—a key figure in McClanahan’s writing here and elsewhere—takes him to see her grave-to-be and demands that he take a picture of her standing beside the stone. “It was like I saw that she was dying right then—real slow—and she knew the secret sound,” he writes. “It’s a sound that all of us hear. It’s a sound that sounds like this. Tick. Tick. Tick. AND NOW A MOMENT TO ONCE AGAIN REMEMBER THE THEME OF THIS BOOK.” Later on, he describes a dream in which he’s eating chicken and gravy with his dead loved ones, “like a Sunday so long ago with all of the dead stuffing themselves full of food cooked with lard, and gravy that will once again clog their arteries and kill their hearts.”

Indeed, McClanahan never for a minute lets the reader forget his primary agenda. Upon returning to West Virginia, what he finds is that the place remains unchanged though many of the people who made up his world there are missing—which means the world he knew is, at core, not the same at all. “I tried to remember all of the people and phantoms I had ever known and loved,” he writes. “I tried to bring them back, but couldn’t.”

Not that this book is a maudlin meditation on the passage of time and its effect on place. McClanahan can be very funny, too, and often grotesque. In one anecdote, he pours beer down the feeding tube of his Uncle Nathan, who has cerebral palsy. In another, a cat known as “AIDS cat,” for its woebegone appearance, taunts a hog and meets an undignified end: “So finally the big daddy hog had enough and reached up and bit AIDS cat’s head plumb off—gulp. The cat’s body fell back and jerked and jimmied and jerked some more, and the big daddy hog stood gobbling it on down.”

Not that this book is a maudlin meditation on the passage of time and its effect on place. McClanahan can be very funny, too, and often grotesque. In one anecdote, he pours beer down the feeding tube of his Uncle Nathan, who has cerebral palsy. In another, a cat known as “AIDS cat,” for its woebegone appearance, taunts a hog and meets an undignified end: “So finally the big daddy hog had enough and reached up and bit AIDS cat’s head plumb off—gulp. The cat’s body fell back and jerked and jimmied and jerked some more, and the big daddy hog stood gobbling it on down.”

You can hear Trademark Appalachia in there, sure. But McClanahan uses this register sparingly. His more consistent voice is stripped of anything that could be considered either cornpone or pretension—instead, it is conversational, blunt and unadorned, so much so that its stripped-down quality calls attention to itself. McClanahan’s voice is the voice of the place he’s channeling, but at the same time it is also keenly aware of itself as an expression of that place.

Which is not to say that Crapalachia is wary of poignancy. McClanahan delivers moments of tenderness throughout the book, dodging any expectations of an edgy, postmodern take on Appalachian culture, but he does so on his own terms: an edge is always right around the bend. Soft-hearted Uncle Nathan, for example, “believed in KINDNESS,” McClanahan writes. “Please tell me you remember kindness. Please tell me you remember kindness and joy, you cool motherfuckers.”

With its frequent direct address of the reader and episodic structure, Crapalachia feels steeped in the dynamics of oral storytelling—a tradition, of course, where fact and fiction are all mixed up in a stew of time and entertainment, and where what really happened is far beside the point. But the book is also informed by the vernacular of contemporary television comedy, whose audiences are encouraged to be aware of, and to chuckle at, the construction of every narrative, every joke, every sentimental moment. The blending of these two registers puts Crapalachia in a category all its own. And perhaps it’s also relevant that McClanahan, whose work can certainly be described as regionalist, has come on the literary scene in the age of the Internet, his reputation built to a significant extent through online channels. As Michael Bible observed in an article for Aljazeera America, McClanahan’s approach to “biography” calls to mind the nature of the Internet itself, which “provides a setting for fictions in its own right, a place of invention, where myth can supersede real life.”

McClanahan is both of and not-of his home-place; he knows this, but don’t expect him to navel-gaze about it, at least not in any conventional sense. Delight, instead, in his deadpan humor, in his toying with the expectations of genre, and in his sharp skewering of indigenous culture as a mediated thing, bought, packaged, and sold to a public ever gullibly hungry for some trace of authenticity. Of Grandma Ruby, McClanahan writes, “She knew how to do things that are all forgotten now—things that people from Ohio buy because it says homemade on the tag. I looked at the quilt she was working on. The quilt wasn’t a fucking symbol of anything. It was something she made to keep her children warm. Remember that. Fuck symbols.”

Scott McClanahan will discuss Crapalachia at the Southern Festival of Books, held in Nashville October 11-13. All festival events are free and open to the public.