Alan Lightman's Dreams

Alan Lightman—scientist, essayist, novelist, and poet—takes on the big questions

Recalling his childhood in 1950s Memphis, Alan Lightman says he was a thoughtful, curious kid. “I was always troubled and awed by the big questions,” he says. “Why are we here? Why is there something rather than nothing? What is the meaning of life? How did the universe begin?” From the time he first asked those big questions, Lightman seems to have understood that there could be more than one avenue for investigating them. As a high school student he showed an avid interest in science and also wrote poetry. He was good enough at both endeavors to snag statewide academic prizes, but science won out, at least initially. He earned a Ph.D. in theoretical physics from the California Institute of Technology in 1974, and spent the next fifteen years as a research scientist at Cornell and Harvard. He is credited with discoveries that have wide application in astronomy and astrophysics.

Even while Lightman the scientist was concerned with stellar dynamics and relativistic plasmas, Lightman the writer was beginning to re-emerge. In the early 1980s he began to publish essays and short fiction that explored the imaginative, creative possibilities of scientific thought. He left his post at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics in 1989 to become a professor of science and writing at MIT. His first novel, Einstein’s Dreams, was published in 1993 and garnered tremendous attention and critical acclaim. In the years that followed, Lightman set research aside and devoted himself primarily to writing and to developing writing programs at MIT. He has published a dozen books, including several collections of his essays and four bestselling, highly regarded novels—Good Benito (1994), The Diagnosis (2000), Reunion (2003), and Ghost (2007). Song of Two Worlds, a book-length narrative poem, appeared last year, and in 2011 Pantheon Books will publish Screening Room, a book about his youth in Memphis.

Even while Lightman the scientist was concerned with stellar dynamics and relativistic plasmas, Lightman the writer was beginning to re-emerge. In the early 1980s he began to publish essays and short fiction that explored the imaginative, creative possibilities of scientific thought. He left his post at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics in 1989 to become a professor of science and writing at MIT. His first novel, Einstein’s Dreams, was published in 1993 and garnered tremendous attention and critical acclaim. In the years that followed, Lightman set research aside and devoted himself primarily to writing and to developing writing programs at MIT. He has published a dozen books, including several collections of his essays and four bestselling, highly regarded novels—Good Benito (1994), The Diagnosis (2000), Reunion (2003), and Ghost (2007). Song of Two Worlds, a book-length narrative poem, appeared last year, and in 2011 Pantheon Books will publish Screening Room, a book about his youth in Memphis.

Scientists who write are no rarity, but Lightman is virtually unique in combining a significant career as a research scientist with an equally significant career as a writer of literary fiction. It’s remarkable for a single person to be touched by such potent analytical and creative genius. Most people experience a certain tension between their logical and affective selves, between cold rationality and a more intuitive, artistic way of interpreting the world. Culture and temperament usually encourage them to nurture one or the other, and to value it more highly. Lightman seems to have escaped that process, giving his intellect free rein in both realms, though he has confessed to feeling his own sense of conflict between them.

“We can reconcile these two different parts of ourselves in the sense that they are both necessary and both aspects of being human,” he writes in a recent email exchange. He doesn’t recommend, however, any attempt to unite these two ways of looking at the world—to “dissolve their differences so that we have a single self, a single dimensionality.” Such a unity of vision would, he says, “have the same negative consequences as forcing all the peoples of the earth to have the same culture, the same language, and the same belief systems. We are far richer human beings by having the dual capacity to write To the Lighthouse as well as The Principia.”

Much of Lightman’s fiction does employ both aspects of that dual capacity, successfully melding abstract ideas with tender human feeling. That’s especially true of Einstein’s Dreams, his most widely read work. The book is a collection of brief vignettes that depict fictional dreams of Einstein as he developed his theory of relativity. The thirty dreams explore the myriad ways that time might operate. For example, in one scenario, future and past are entangled, creating an unpredictable world in which effect can precede cause. In another, time is “sticky”—people and places become glued to random moments, thus becoming perpetually out of sync with the rest of the world. The book would just be a clever thought exercise, a little sci-fi brain teaser, if not for Lightman’s delicately wrought prose and his gift for conveying the joy and torment of the people trapped in these alternate worlds. The genius of the novel is that it depicts ordinary, real-world dilemmas in a fresh way. We identify with the mother who is stuck in the moment when her young son adored her, or with the man who, unable to know his own past actions, cannot understand why his friends have abandoned him.

Einstein’s Dreams spent seventeen weeks on The New York Times bestseller list when it appeared. It has been translated into thirty languages, shows up frequently on college reading lists, and has inspired numerous theatrical and musical productions. That’s an amazing degree of response to a slim novel that has no real plot and just a few brief scraps of dialogue, but it’s no surprise readers are so powerfully drawn to it. There’s something profoundly satisfying in the way it speaks to both the heart and the head. It turns a dual lens on the questions Lightman pondered as a boy, portraying the human condition with particular depth.

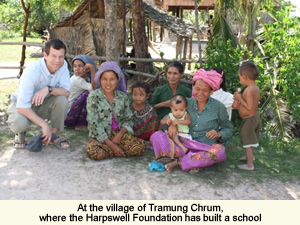

In addition to launching Lightman’s career as a novelist, Einstein’s Dreams led to the project that has become something of a third vocation for him. Frederick Lipp, a Unitarian minister who was working with villagers in rural Cambodia, contacted Lightman about using the book in a sermon. The two men became friends, and Lightman accompanied the minister to Cambodia in 2003, Lightman was deeply moved by the desire for education among the people, particularly the women. He and his wife, painter Jean Greenblatt Lightman, had established the non-profit Harpswell Foundation in 1999 with the intention of one day devoting themselves to helping those in need, and the plight of the Cambodians provided an opportunity. The foundation is now dedicated to promoting education and leadership training for children and young women in the developing world. Lightman presently devotes half his time to working and fundraising for the foundation, and he is involved in the day-to-day management of a dormitory for women students in Phnom Penh. He has described his humanitarian work as life-altering and the most satisfying thing he’s ever done. He spends about six weeks a year in Cambodia, where he says his experiences “have changed me as a person and affected my thoughts and my writing.”

In addition to launching Lightman’s career as a novelist, Einstein’s Dreams led to the project that has become something of a third vocation for him. Frederick Lipp, a Unitarian minister who was working with villagers in rural Cambodia, contacted Lightman about using the book in a sermon. The two men became friends, and Lightman accompanied the minister to Cambodia in 2003, Lightman was deeply moved by the desire for education among the people, particularly the women. He and his wife, painter Jean Greenblatt Lightman, had established the non-profit Harpswell Foundation in 1999 with the intention of one day devoting themselves to helping those in need, and the plight of the Cambodians provided an opportunity. The foundation is now dedicated to promoting education and leadership training for children and young women in the developing world. Lightman presently devotes half his time to working and fundraising for the foundation, and he is involved in the day-to-day management of a dormitory for women students in Phnom Penh. He has described his humanitarian work as life-altering and the most satisfying thing he’s ever done. He spends about six weeks a year in Cambodia, where he says his experiences “have changed me as a person and affected my thoughts and my writing.”

Perhaps those changes are part of what led Lightman to write his most recent book, Song of Two Worlds. After seventeen years of success as a novelist, this long narrative poem represents a radical departure from his usual form. Though it takes on many of the themes that have driven his fiction—time, memory, personal identity, faith, and the tension between the logical and the emotive selves—the use of verse allows Lightman a freer, more impressionistic means of addressing them. The poem largely consists of the interior monologue of a troubled, aging man who has abandoned his family and returned to his ancestral Mediterranean home. He’s an educated man, a man of science, who is obsessed with the same big questions that haunted young Lightman.

I knock on the door of the universe.

Here, this small villa, this table, this pen.

I ask the universe: What? And Why?

The book is divided into two sections, reflecting the “two worlds” of the title. In the first section, titled “Questions with Answers,” Lightman’s mysterious narrator seeks comfort in science and mathematics. Great thinkers such as Darwin, Lavoisier, and Einstein are celebrated for their insights and sometimes skewered for their personal foibles. A typical passage considers Isaac Newton:

Suspicious recluse,

You grasped the gears

Of the galactic clock.

You made the mortal immortal.

Much of “Questions with Answers” is a paean to the certainties of logic—”Pure sines, derivatives / Dazzle the air, sing in their hard arcs”—but the narrator finds that his existential questions still haunt him, at one point showing up personified as “the Voiceless,” who ” … throws stones at my house, / Rolls his eyes back and forth, / Gestures to open my door. / I refuse.” Ultimately, the narrator is unable “to shake off this dark clinging thing,” and in the second part of Song of Two Worlds he confronts “Questions without Answers.” He invokes a different set of wise ones here—Lao-Tsu, Rembrandt, Omar Khayyam—but most of his thoughts are devoted to the state of his own soul. As his devoted attendant dies, he obsesses over the loss of his family and wonders how he might have become a different man. All his questions ultimately resolve to spiritual yearnings and doubts.

God of all Gods or none?

Something or nothing?

Mind or mindlessness?

Speak, I will hear you, I’m waiting.

Song of Two Worlds begins with an epigraph from Gitanjali, a poetic spiritual meditation by the great Bengali poet Rabindranath Tagore. Tagore, who won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1913, was a gifted writer, painter and musician, but his mystical poetry has been his primary legacy in the English-speaking world. Lightman, who describes himself as a longtime admirer of Tagore’s poems, credits Gitanjali with sparking the idea for Song of Two Worlds.

“I must have first read Gitanjali ten years ago,” he recalls. “It is a long poem that expresses, in simple language and pastoral images, Tagore’s faith in God and his complete surrender to God. I asked myself if I had such extreme faith in anything, and I realized that I have great faith in the power of asking questions. That inspiration was the beginning of Song of Two Worlds.”

The profound questions that trouble the narrator—and his commitment to dual ways of seeing the world—may be shared by his creator, but Lightman says he is not the “I” of the poem. “The narrator of the poem is not me. Like the narrator, I am searching for meaning in the world and in my own brief flicker of a life. Unlike me, the narrator once believed in God.” Lightman, who describes himself as a “spiritual atheist,” was raised a Reform Jew and maintained a friendship for many years with Rabbi James Wax, a prominent Memphian who was very active in the civil rights movement. Lightman leaves open the possibility that his narrator might eventually rediscover his belief, but says his own spirituality isn’t motivated by a similar quest. “For me, spirituality and the discovery of meaning in the world do not require belief in God or enrollment in a religious institution.”

Lightman is a strong believer in the value of solitude. “Attention to the profound questions of existence is an inner journey,” he says. “It is difficult to undertake such a journey when we are being bombarded with the noise and frenzy of the world around us.” He has long expressed doubts about the personal and cultural impact of our omnipresent electronic media, and his doubts have not diminished as the Internet and its attendant technologies have become increasingly powerful. “All this connectedness can certainly be an asset,” he says, “but I think it is also critical that we find moments when we can unplug and enter the private world of our own inner selves. To be creative, we must live in these quiet spaces and be able to hear the soft murmurings that take place there.”

Lightman is a strong believer in the value of solitude. “Attention to the profound questions of existence is an inner journey,” he says. “It is difficult to undertake such a journey when we are being bombarded with the noise and frenzy of the world around us.” He has long expressed doubts about the personal and cultural impact of our omnipresent electronic media, and his doubts have not diminished as the Internet and its attendant technologies have become increasingly powerful. “All this connectedness can certainly be an asset,” he says, “but I think it is also critical that we find moments when we can unplug and enter the private world of our own inner selves. To be creative, we must live in these quiet spaces and be able to hear the soft murmurings that take place there.”

Lightman’s work-in-progress is set in a time when those quiet spaces were a little easier to find. He describes Screening Room as a “partly fictionalized memoir” based on his recollections about growing up in Memphis in the 1950s and 60s. Lightman’s family owns a chain of movie theaters, which once included the flagship Malco movie palace at Main and Beale (now the Orpheum Theater). Lightman promises Screening Room will be about his family and the movie business, but also about his hometown. He plans to touch on the culture, food, and music of Memphis, with reflections on Elvis, Martin Luther King, and Boss Crump. It’s a rich story, one that will no doubt be shaped by Lightman’s characteristic insight, and rendered in his exquisite, flickering prose.

READ an excerpt from Alan Lightman’s work in progress, Screening Room.