All the World’s a Stage

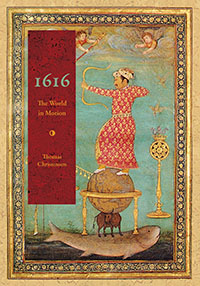

In 1616 Thomas Christensen collects enchanting stories and striking art to describe a world in motion

Reading 1616: The World in Motion is like feasting at a banquet in an old, lavish castle—you get overwhelmed by all the delights. In it, Thomas Christensen uses one year to frame a rich series of narratives about a new, more modern world. He writes of a developing global economy, of changing roles for women and artists, and of travelers who connect Europe, the Americas, and Asia. Packed with illustrations selected and arranged by the author, the book is visually lush and full of surprises.

The accomplished historian, editor, translator, and illustrator recently answered questions via email from Chapter 16 in advance of two Memphis events. Christensen will deliver the keynote address of the 1616 Symposium at Rhodes College, when scholars from across the liberal arts will explore the global developments that occurred in the same year that William Shakespeare died. He will also speak at the Benjamin L. Hooks Central Library in connection with Bookstock 2016:

The accomplished historian, editor, translator, and illustrator recently answered questions via email from Chapter 16 in advance of two Memphis events. Christensen will deliver the keynote address of the 1616 Symposium at Rhodes College, when scholars from across the liberal arts will explore the global developments that occurred in the same year that William Shakespeare died. He will also speak at the Benjamin L. Hooks Central Library in connection with Bookstock 2016:

Chapter 16: Why focus on 1616? At first glance the year does not have the iconic resonance of, say, 1492 or 1968.

Thomas Christensen: The year chose me. I woke up one morning with that date in my head and the resolution to write about it already formed. After publishing 1616 I toyed with doing a follow-up on another year, but it just wasn’t the same.

In years with decisive events like the ones you mention, those events tend to be so overwhelming that they color everything, and it is hard to see beyond them. Those are hinge years, but their great events are nearly always the result of forces that had been building up in previous years. There are plenty of momentous events in 1616, but none that overwhelms the narrative. It’s a good year to see what is going on globally during this period of history.

Looking at things in isolation, our knowledge can get siloed. We might read Shakespeare, for example, but have only a dim understanding of events in the Americas, Central and West Asia, or East Asia that informed his work and his world. There’s a reason his company chose “The Globe” as the name of their theater: the world was newly global, and many people were keenly aware of that. Focusing on a single year helped me to keep a global perspective.

And the year 1616 is full of great stories. It was a time of unsettling change. With the new maritime globalism connecting far-flung places, there were many marvelous encounters and discoveries. It was a bold and extravagant time, marked by grand gestures. It turned out to be a Goldilocks year for me: not too early, not too late, just right.

Chapter 16: Although you explore important themes in global history, this book seems less driven by a thesis than by your own curiosity and enthusiasm for stories. Is that a fair characterization?

Christensen: Yes, that is fair. This is not a particularly didactic or argumentative work. I happily confess to “curiosity and enthusiasm.” That said, the main point that I think emerges from the book and all of its stories is that the world of 1616 was a highly connected one: global connectivity was greater than is often realized or acknowledged. Most of the stories in the book underscore this theme.

Christensen: Yes, that is fair. This is not a particularly didactic or argumentative work. I happily confess to “curiosity and enthusiasm.” That said, the main point that I think emerges from the book and all of its stories is that the world of 1616 was a highly connected one: global connectivity was greater than is often realized or acknowledged. Most of the stories in the book underscore this theme.

I started by collecting the stories. I tried to use the best sources and to bring something new to each of the stories. At one point I had a twelve-chapter plan that revolved around one event from each month of the year. But the stories resisted that. They called for fewer topics that would allow more amplitude to each. They sorted themselves into the five of the final book: the silver-and-silk economy, the changing roles of women, new directions in the visual arts, emerging science, travel and cross-cultural exchange. I wanted to give the flavor of the time. It was a world, like ours, that was recoiling from the shock of the new, while also setting off in brave and unprecedented directions. It was a world in motion.

Chapter 16: Art is central to 1616: A World in Motion. You describe an ascending generation of artists who embrace the role of social critic, and you use a huge array of gorgeous, intriguing, and/or quirky historical images. What can art reveal to the historian?

Christensen: Having worked for many years at an art museum, I’m a believer in object-oriented history. So much about a particular place and time can be learned from just looking closely at a single object. Gradually a sense of the moment unfolds, and connections ripple outward.

Certainly the way that we see things changes over time. Still, a historical object can offer a very nearly unmediated presence of its moment. In itself it’s a tangible thing, unlayered by prior interpretations. Of course you want to be informed about the context of the objects you’re looking at, but there is also a level on which you respond directly, not dependent on the interpretations of others and not, in many cases, hindered by language differences that can impede you when working with texts. Images also punctuate and bring relief to what would otherwise be a rather unrelenting narrative.

Chapter 16: You illustrate the rise of a true network of global trade during this era, centered in some respects around the city of Acapulco, Mexico. Why Acapulco?

Christensen: Early modern maritime globalism relied on enormous vessels called galleons. These great ships weighed one to two thousand tons. The galleons, departing from Acapulco, carried silver from the Americas—in the form of Spanish dollars, the model for our own currency—to Manila in the Philippines. From there the silver was taken to China, where it was used as the official currency of the late Ming dynasty. In exchange, luxury goods, especially silks, were returned to the Americas, to Acapulco. From there most of the goods were transported across Mexico to Veracruz to be taken to markets in Europe.

Because these ships were so large, there were few ports capable of accepting them. Acapulco was considered one of the best because the land drops off so sharply that the port waters were deep enough for the galleons to approach quite close to shore. Also, Acapulco bay is sheltered, protected from storms and defensible against pirates.

The galleon trade was strictly regulated by the Spanish crown. To keep a close eye on that trade the authorities made it illegal to use any other port than Acapulco for the trans-Pacific trade. It’s pretty hard to hide a galleon, so the sea captains were obliged to comply. The global economy was based on silver, and eighty percent of it came from the Americas. Acapulco by all accounts was a pretty miserable place, and yet it was one of the most important spots in the world, because the bulk of the world’s wealth passed through it.

Chapter 16: You profile women of many stations and backgrounds, from rulers to prostitutes to witches. What, if anything, unites their experiences?

Christensen: Take another year: we might ask, what unites women’s experiences in 2016? It’s difficult to generalize about such a large number of people in such a variety of circumstances. What I do in the book is look at a kind of cross-section: a Native American “princess,” some English royal ladies, a Puritan woman, a French midwife, a Mughal queen, prostitutes in Edo and elsewhere, various women accused of witchcraft, a carousing Londoner known as the Roaring Girl, a Basque woman who passed as a man and served in combat, and a great Italian painter (Artemisia Gentileschi), among others. Of course, the stories of these women come down to us because they were exceptional, and most women lived lives that left few if any records.

But we could say that the early modern world was reeling from vast changes in the global economy, international politics, technology, and social structures. For most women, personal opportunities were severely constrained. But some were able to take advantage of the changes to fashion new roles, and often to accomplish remarkable things. Most of the women I profile fit into this category.

Chapter 16: “A great many people were on the move in 1616,” you write. We meet tourists, ambassadors, merchants, slaves, and others whose lives straddle boundaries of nation and culture. What was the impact of all this travel? How can individual stories illuminate a global history?

Christensen: There are a lot of ways to “do history.” I’m a great admirer of researchers who are able to collect new data and analyze it to draw conclusions about distant times. But history began as storytelling, and people everywhere seem to have an innate predilection for narrative. We learn with stories and shape our understanding of the world through them. We talked earlier about object-oriented history. The stories of individual people are like that on the level of narrative. They are particular cases that stand as specimens of life in their time.

Of course, it’s worth remembering that the stories that have come down to us are those of individuals who were exceptional in some way. History is also made by those who remain nameless, or who are little more than names to us. In some ways they are the most important. But my book is inevitably skewed to those who were exceptional, and their stories can be inspiring, unsettling, and enlightening.

Historians call the early seventeenth century the “early modern” age. Its dynamics set the course for the world we know. All this travel made the world both larger and smaller. People were forced to have a greater awareness of distant peoples and places. New connections caused new understandings, and new misunderstandings. But the world also shrank. The shadowy fantastic fringe that had been thought the home of unicorns, dwarves, two-headed people, and other marvels shriveled in the light of experience. The whole world was becoming mapped and known.

Aram Goudsouzian chairs the history department at the University of Memphis. His most recent book is Down to the Crossroads: Civil Rights, Black Power, and the Meredith March Against Fear.