Alone in the Locker Room, Bleeding

Andrew Maraniss’s Strong Inside is a superb biography of SEC basketball pioneer Perry Wallace

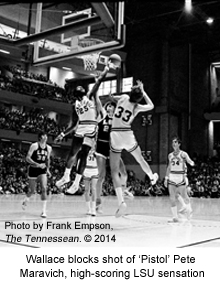

On February 9, 1968, a few minutes after Vanderbilt forward Perry Wallace came onto the basketball court against Ole Miss, a Rebel player hit him in the head, hard. Blood streamed down Wallace’s face; he couldn’t see. Neither referee called a foul or even stopped the game. Wallace had to wait for a dead ball to be escorted to the locker room.

None of this was surprising. Wallace was black, and this was 1968, in Mississippi. Just five years earlier, federal marshals had clashed with students trying to prevent James Meredith from integrating the school. And Wallace wasn’t just black—he was the first and only black player on Vanderbilt’s team, or any team in the SEC, at a time when college sports in the Old Confederacy was one of the last bastions of segregation.

None of this was surprising. Wallace was black, and this was 1968, in Mississippi. Just five years earlier, federal marshals had clashed with students trying to prevent James Meredith from integrating the school. And Wallace wasn’t just black—he was the first and only black player on Vanderbilt’s team, or any team in the SEC, at a time when college sports in the Old Confederacy was one of the last bastions of segregation.

Wallace had already suffered the racist taunts of thousands of Ole Miss fans. During warm ups, they laughed whenever he missed a shot and booed when he made one. After he was struck, they cheered as he stumbled off the court. And they booed again when he returned to the court for the second half—and then sat in sullen silence as he led his team to a 90-72 win.

Wallace’s performance was a triumph of determination and personal strength over hatred and violence. But consider this: he had sat alone in that locker room, bleeding. No coach came to check on him, no teammate. “As he walked toward the tunnel to return to the bench for the second half,” Andrew Maraniss writes in Strong Inside, his superb new biography, “Wallace understood more clearly than ever that his journey as a pioneer was one that he would be making alone.”

Like any great biography, Strong Inside is about more than just its subject. It is a history of Vanderbilt, of Nashville, of the SEC; a history of basketball and Southern sports culture and how they clashed, time and again, with the forces of civil rights that transformed America in the 1960s. Above all it is a meditation on the personal price of progress, about what happens to the people we ask to be racial pioneers, and what we—as whites, as blacks—owe to them in return.

Like any great biography, Strong Inside is about more than just its subject. It is a history of Vanderbilt, of Nashville, of the SEC; a history of basketball and Southern sports culture and how they clashed, time and again, with the forces of civil rights that transformed America in the 1960s. Above all it is a meditation on the personal price of progress, about what happens to the people we ask to be racial pioneers, and what we—as whites, as blacks—owe to them in return.

As a star player and valedictorian at Pearl High School in North Nashville, Wallace had his pick of scholarship offers. He had no particular desire to stay in the South; he was aware of the civil-rights movement—no one in Nashville in the mid-60s could ignore it—but he had no interest in being a racial pioneer. Still, Vanderbilt lured him with promises of a strong academic career, something he feared the powerhouse state schools in the North couldn’t offer.

Vanderbilt, under the leadership of president Alexander Heard, was eager to bolster its progressive image, the better to compete with the Ivy League and other top private schools. But if Heard meant well, his campus didn’t always agree. From the day he arrived, Wallace was largely shunned—by professors, by fellow students; he was forbidden to attend services at the University Church of Christ after a few powerful members protested. His coach, Roy Skinner, treated him fairly but without a hint of recognition about the experiences that set Wallace apart from the rest of the players and might call for a little additional support.

And it soon became clear that Vanderbilt was happy with Wallace as a token. There were a handful of other black students on campus, but the only other black player on the team, Godfrey Dillard, was cut before his junior year; he then left school and returned home to Michigan. When Wallace graduated in 1970 he was still one of the only minority students among the thousands of Vanderbilt undergraduates.

And it soon became clear that Vanderbilt was happy with Wallace as a token. There were a handful of other black students on campus, but the only other black player on the team, Godfrey Dillard, was cut before his junior year; he then left school and returned home to Michigan. When Wallace graduated in 1970 he was still one of the only minority students among the thousands of Vanderbilt undergraduates.

A few weeks before graduating, Wallace sat down with Frank Sutherland, a young reporter for The Tennessean (and later its editor). After years of being a quiet team player, Wallace unloaded on the university. He accused its recruiters of misleading him into thinking he would actually be welcomed into campus life; he criticized the administration for failing to bring more black faces to campus; and he lashed out at the student body for cheering him on the court and shunning him in the halls. Several days later, Wallace gave another interview, this time to the student-run Hustler newspaper, in which he said he regretted ever coming to Vanderbilt. “If I had to do it over again, I would go to school somewhere in the East or the West.”

The two articles were a gut-check to the Vanderbilt and Nashville communities, and they rendered Wallace persona non grata for decades. Not that he needed them: Wallace went on to Columbia Law School, after which he worked for the Justice Department before going into academia; today, he teaches law at American University.

The two articles were a gut-check to the Vanderbilt and Nashville communities, and they rendered Wallace persona non grata for decades. Not that he needed them: Wallace went on to Columbia Law School, after which he worked for the Justice Department before going into academia; today, he teaches law at American University.

But as admirable as he is, Wallace is also an exception. As Maraniss noted in his appearance at last month’s Southern Festival of Books in Nashville, many of the black athletes who led the way into Southern sports were scarred by the experience, and their post-college lives suffered for it. Several didn’t graduate, and few have done anywhere near as well as Wallace. The strain of being both celebrated and denigrated was simply too much.

In recent years, Vanderbilt has tried to make amends, inviting Wallace back to campus and retiring his jersey. But there is more to do— not only for him, but for the many other, mostly unknown, black athletes who integrated other corners of Southern sports. It is very easy, and right, to laud these men (and, soon after, women) as heroes. Wallace’s story, told so well in Strong Inside, makes us ask whether such praise can ever be enough.

[To read a Chapter 16 essay by Perry Wallace about his Vanderbilt experience, please click here.]

Nashville native Clay Risen is the author of A Nation on Fire: America in the Wake of the King Assassination and American Whiskey, Bourbon and Rye: A Guide to the Nation’s Favorite Spirit. His new book, The Bill of the Century: The Epic Battle for the Civil Rights Act, appeared in spring 2014. He lives in New York, where he is an editor at The New York Times.