American Tragedy

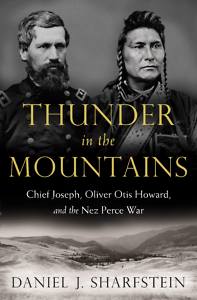

Daniel J. Sharfstein captures two larger-than-life opponents of the Nez Perce war in Thunder in the Mountains

Last year, when actress Shailene Woodley was arrested while protesting the Dakota Access Pipeline, the young star of Big Little Lies was following a long tradition of celebrity protest against the taking of Native American lands by a seemingly unstoppable U.S. government. That tradition of public dissent, the horrific war that led to it, and the two men who commanded the opposing sides are all skillfully rendered in Thunder in the Mountains: Chief Joseph, Oliver Otis Howard, and the Nez Perce War by Daniel J. Sharfstein, a professor of law and history at Vanderbilt University in Nashville.

Sharfstein’s previous book, 2011’s The Invisible Line, examines the complexity of race in America. While working on that book, Sharfstein stumbled upon an intriguing 1878 letter to Oliver Otis Howard, a Union Army general who became a champion of African American equality. But this same champion of minority rights, who lost his right arm in the Battle of Fair Oaks in 1862 and for whom Howard University is named, also waged a brutal war against the Nez Perce in 1877, one that ultimately forced the vanquished survivors into exile from their native lands.

If the seeming contradictions in Howard’s personality provide Sharfstein with the start of a good story, they are matched by those of Howard’s opponent, Chief Joseph, who spent five years peacefully advocating on behalf of his people before embracing war. After his defeat and exile, the eloquent leader became the “sensation of Washington” and a star of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show. His statement of surrender, which included the famous (if later disputed) line, “I will fight no more forever,” was memorized by generations of schoolchildren, becoming the second most recited school speech after the Gettysburg Address.

With this newfound celebrity, Chief Joseph continued to advocate for Native American rights, ultimately influencing official U.S. policy. He befriended and enlisted two of Howard’s former aides, Nelson Miles and Charles Erskine Scott Wood, both of whom helped argue in Washington for fair treatment of the Nez Perce families. On January 14, 1879, Joseph was received at the White House by President Hayes. Among those in the reception line was William Tecumseh Sherman. “During the war, Sherman had pictured Joseph swinging from the gallows,” Sharfstein writes. “Now he shook the chief’s hand.”

The paths of Joseph and Howard were lengthy and complex, as were the ideas with which they continually wrestled—and these facts alone might explain the 600-page length of Sharfstein’s book. But despite its great length, the structure of Thunder in the Mountains is simple and direct, exploring the lives of each man toward their ultimate meeting, the heart-wrenching details of the conflict at the book’s center, and the ways in which the war forever changed both men and drove them—and many of those closest to them—toward a sense of mutual understanding.

The paths of Joseph and Howard were lengthy and complex, as were the ideas with which they continually wrestled—and these facts alone might explain the 600-page length of Sharfstein’s book. But despite its great length, the structure of Thunder in the Mountains is simple and direct, exploring the lives of each man toward their ultimate meeting, the heart-wrenching details of the conflict at the book’s center, and the ways in which the war forever changed both men and drove them—and many of those closest to them—toward a sense of mutual understanding.

While the book is a thorough and well-documented work of history, it delves into the human condition like the best fiction, offering insights not only into historical events but also into the ways people can grow and evolve. This novelistic approach to character is immediately evident when Howard first meets Chief Joseph, two years before their ultimate hostilities:

The chief was more than six feet tall. He had high broad cheekbones and large eyes, a square jaw and strong chin. At thirty-five years old, he was a decade younger than the general, his face just beginning to crease—at the mouth, his brow, the corners of his eyes—despite a lifetime in the sun, snow, and wind. He stepped close and looked down at Howard, black eyes to blue. Howard looked at Joseph. They stood still, hand in hand, until the time began to stretch. Though Joseph towered over Howard, the general did not feel threatened or intimidated. The chief’s gaze did not strike Howard as “an audacious stare.” Instead, the general felt something else. It was hard to define. Joseph was showing strength, Howard thought, but also vulnerability. “He was trying to open the windows of his heart to me,” Howard wrote later of that moment, “and at the same time endeavoring to read my disposition and character.”

Decades later, Chief Joseph’s physical bearing and penetrating gaze prompted one obituary writer to call him “a composite of all the virtues of an ideal Indian chief of the Fenimore Cooper type.” But the man himself becomes much more than a cliché in Sharfstein’s able hands: Joseph turned his former enemies—even, later in life, Howard—into allies as he launched a campaign for Native American rights that resonates all the way to the Dakota Access Pipeline. Thunder in the Mountains is a great and bloody war story to be sure, but it is also a careful meditation on human rights, the reach of government, and the power of a lone voice speaking truth.

Michael Ray Taylor teaches journalism at Henderson State University in Arkadelphia, Arkansas. He is the author of several books of nonfiction and coauthor of a textbook, Creating Comics as Journalism, Memoir and Nonfiction.