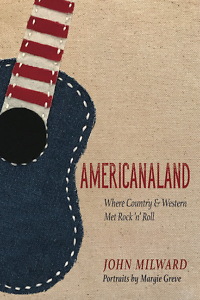

Americanaland the Beautiful

John Milward’s survey of Americana music positively sings

John Milward’s Americanaland is a book with a sense of place and rhythm. Both are impeccable. The joy of this veteran music writer’s survey of the music that’s come to be called Americana is that he ranges far, digs deep, and dismisses no sound.

How else would we meet not only the Carter Family and Jimmie Rodgers, but also Muddy Waters and Howlin’ Wolf, with nods to Steve Earle and Gillian Welch along the way, all in just the first chapter? How else would we get from mountain holler to lost highway, Memphis to Laurel Canyon, the Dust Bowl to Big Pink, for less than the cost of a tank of gas?

We’re funny about our music sometimes. We get caught up in what we call it. There are genres and subgenres, and into the cubbyholes they go, the singers and their songs. But that’s not how the best music is inspired and shaped, made and forever remade. It’s a force, like wind or water, sometimes raised to the level of magic; it goes where it wants and changes as it goes.

Milward, former chief pop music critic for USA Today and the Chicago Daily News, understands all this. So he spreads his arms wide. He perks his ears, picking up signals and making connections. He gets at where Hank Williams got “the feral sound of his yodel” and Lucinda Williams her songs “thick with love, regret, and the urge for going.”

He’s telling a story of American music, and of America. We’re a better country, in this musical version, closer to our supposed ideals — musicians have always tended to be far more colorblind than the general population. They may be some of the most flawed humans who ever lived, but bless ’em, they appreciate a good song, no matter the source.

Musicians, at their best, see with their ears. How else did Elvis’ first Sun single come to have a hopped-up blues song (“That’s All Right”) on one side and a hot-wired bluegrass number (“Blue Moon of Kentucky”) on the other?

Musicians, at their best, see with their ears. How else did Elvis’ first Sun single come to have a hopped-up blues song (“That’s All Right”) on one side and a hot-wired bluegrass number (“Blue Moon of Kentucky”) on the other?

Elvis and his Sun label mates are here. Chuck Berry, too. Bob Dylan. The American music-mad Beatles. And Ray Charles, who by cutting his Modern Sounds in Country and Western Music became “an American roots-music star, and as such,” Milward writes, “a seminal figure in Americana.”

There are no walls in Americanaland — only tall trees with deep roots, and singers and pickers gathered there in the shade, trading lines and taking long pulls from the jug of song. It’s OK to be under the influence here, even if you’re blazing down the lost highway in a pink Cadillac.

This music is all about influences — Little Richard and Buddy Holly’s on Dylan; Dylan’s on everybody who picked up an acoustic guitar and tried to string words together in some profound or confounding new way.

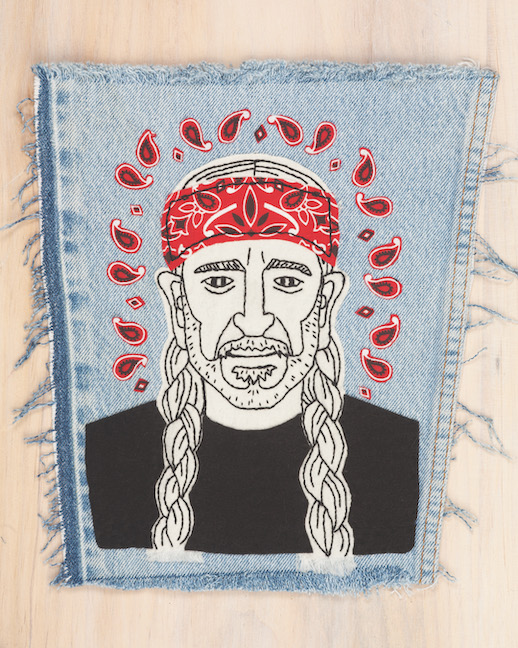

That’s how it’s done: Soak up those influences, and then make it sound like you. How else did we get such roots-oriented originals as Joni Mitchell, Neil Young, Willie Nelson, John Prine, and Dolly Parton?

Notice that the first two on that list aren’t even from America. No matter, because in Americanaland, you don’t have to “show your I.D. at the door,” to quote from the Flying Burrito Brothers’ “Sin City.” You don’t need letters of transit.

In the chapter called “Grievous Angels,” inspired by a Gram Parsons song, the Rolling Stones decamp to the south of France and record Exile on Main Street, “as dark and rootsy an Americana album as could be made by a band of British rock stars.”

Speaking of Brits, there was Richard and Linda Thompson’s Shoot Out the Lights, “about a relationship on the rocks that suggested Dylan’s Blood on the Tracks,” Milward writes, “with better guitar solos.”

In Americanaland, your origin story need not begin in a shotgun shack or backwoods cabin. You don’t have to have turned 21 in prison or shot a man in Reno. As Milward points out, Alison Krauss “grew up not in a rural mountain holler but in the college town of Champaign, Illinois.” And Gillian Welch was adopted at birth by “a showbiz couple” who moved the family to Los Angeles when they were hired to write music for The Carol Burnett Show.

If it seems like Americana music, as defined by Milward, isn’t just a big tent but everything under the sun, think of it this way: The music herein is generally made by men and women, not machines and studio trickery. It’s driven more by a love of song than a lust for fame, though Elvis did want, and did get, that pink Cadillac. It’s crafted, not calculated. (Talking about you, Pop.) Well, except for the Eagles, who really were in it for the money and fame, and sounded like it, much of the time.

As befitting the size and scope of Americanaland, Milward’s history covers a staggering amount of ground, but without the journey ever seeming rushed. There are no wrong turns or lost weekends — although, to quibble, I’d have spent more time on cowpunk and less on Nanci Griffith.

But that’s me. This is Milward’s book, and it’s a really fine one, about a place that’s at once mythical and real, vast and intimate, not with one national anthem but thousands, and more being written and sung every day.

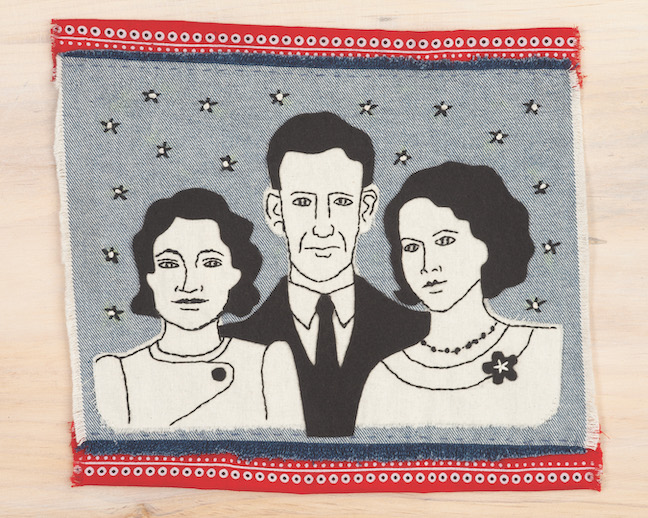

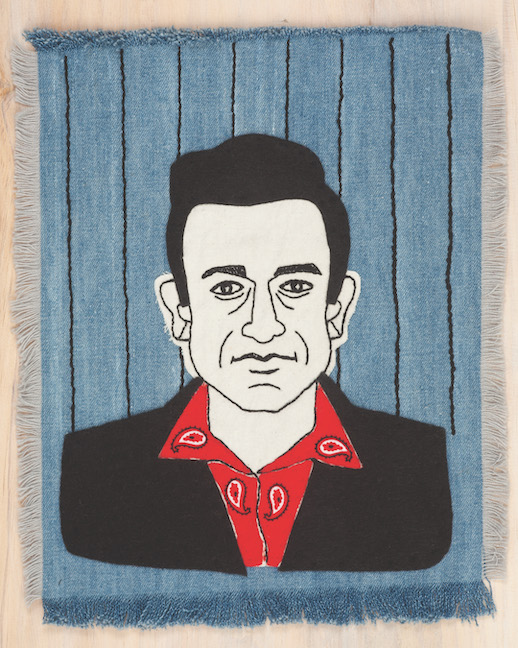

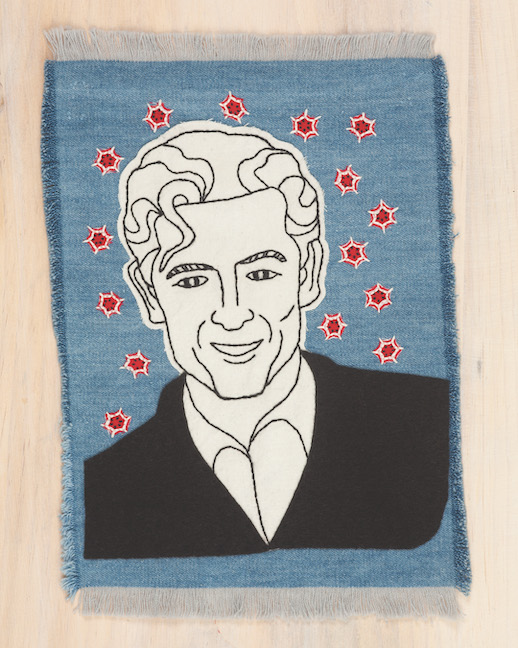

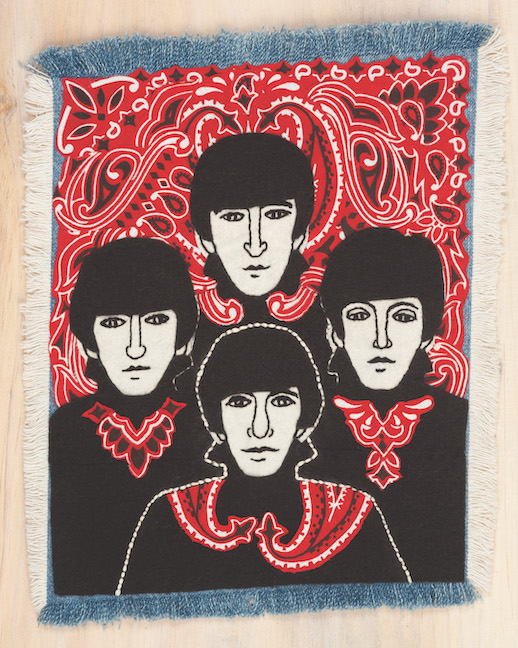

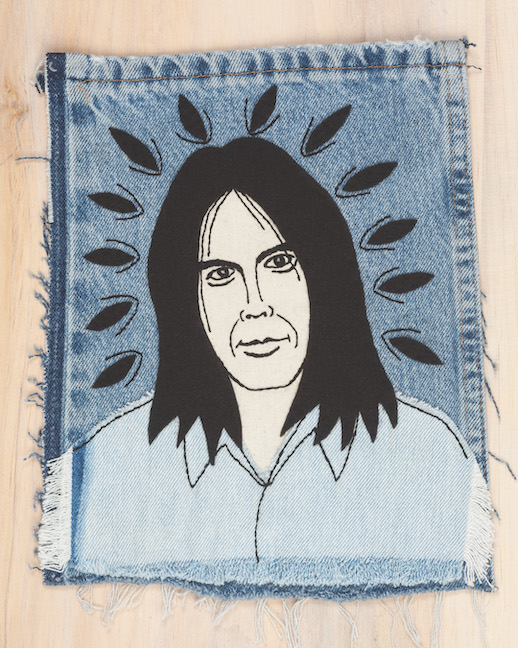

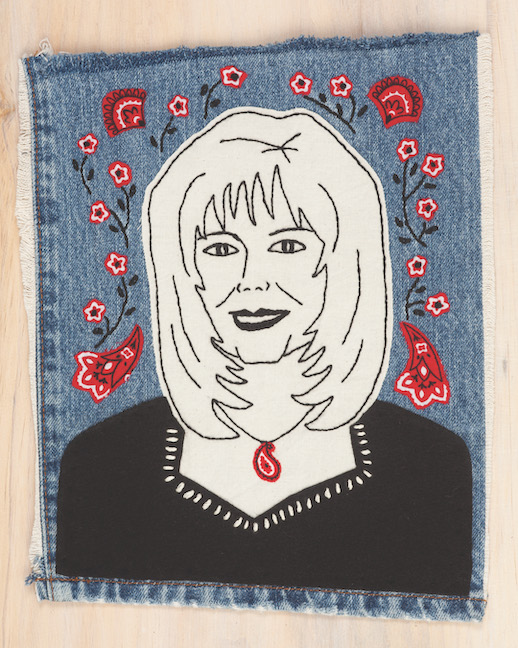

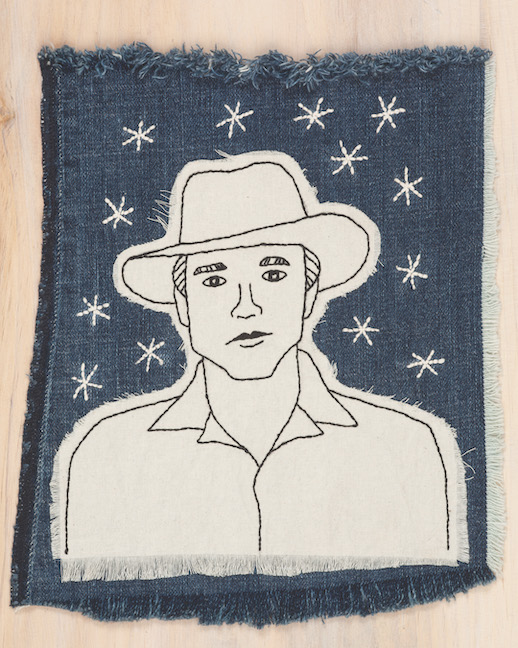

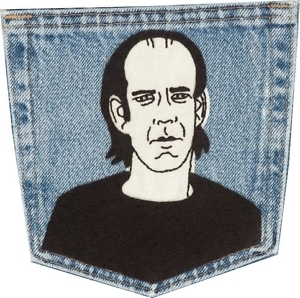

Americanaland includes more than two dozen hand-embroidered color portraits of notable Americana musicians by artist Margie Greve. A selection of these portraits appears below. See more at Greve’s website.

David Wesley Williams is the author of the novel Long Gone Daddies (2013), and his short fiction has appeared in Oxford American, Kenyon Review Online, and in Akashic Books’ Memphis Noir. He lives in Memphis.