America’s Cracked Mirror

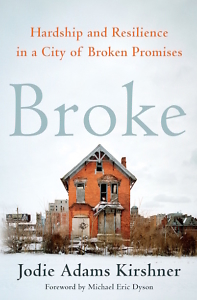

In Broke, Jodie Adams Kirshner shines a light on the precarious lives in Detroit’s neglected neighborhoods

In an author’s note at the end of Broke, Jodie Adams Kirshner expresses her hope that “by understanding Detroit’s experience” of bankruptcy in 2013 “we may push for better outcomes for other cities.” Note that Kirshner offers no optimism for Detroit’s own future, nor does she suggest that Michigan politicians will learn from their mistakes quickly enough to improve the lives of the poor citizens she profiles in the book.

Broke’s subtitle, Hardship and Resilience in a City of Broken Promises, indicates the author’s intention to counter the prevailing narrative that Detroit has revived since bankruptcy. Even as the city transformed itself from Motor City to “Techtown,” she contends, its socio-economic profile remained peculiarly inside-out. “Two-thirds of city residents continued to commute to low-skilled positions in the suburbs,” Kirshner notes, “while 200,000 suburbanites enjoyed high-skilled positions in the city.”

Broke’s subtitle, Hardship and Resilience in a City of Broken Promises, indicates the author’s intention to counter the prevailing narrative that Detroit has revived since bankruptcy. Even as the city transformed itself from Motor City to “Techtown,” she contends, its socio-economic profile remained peculiarly inside-out. “Two-thirds of city residents continued to commute to low-skilled positions in the suburbs,” Kirshner notes, “while 200,000 suburbanites enjoyed high-skilled positions in the city.”

Nashville native Kirshner, a research professor at New York University who teaches bankruptcy law at Columbia Law School, focuses on Detroiters who have not participated in the renewal. She performed hundreds of interviews in the city, hearing heartrending stories of locals whose simple ambitions — stable work, safe homes, decent schools — are continually thwarted by circumstances outside their control. To illustrate their daily challenges, Kirshner tells the stories of five residents of the “neighborhoods,” Detroit’s euphemism for the blighted districts lying between the resurgent downtown and the comfortable suburbs. She also describes two outsiders, a Los Angeles real estate developer and a New Jersey tree surgeon, who each moves their operations to Detroit, with dramatically different results.

Among the insights Broke offers, the most salient is that the vast majority of Detroit’s urban poor lead a precarious existence. They live every day with the uneasy feeling that one wrong move will plunge them into the abyss. If their income is interrupted, they start playing whack-a-mole with bills, paying bits of one, avoiding others, trying to stay one step ahead of having their water shut off or getting evicted. “You paying Peter to pay Paul and then you’re just staying afloat,” as a struggling construction worker describes his finances. “And if you get a flat or a ticket or something else, your life change. It puts you in a hurdle.”

While these snapshots provide readers an emotional connection to Kirshner’s subjects, the author buttresses her points with statistics that reveal Detroit’s dire realities. “Between 2000 and 2012,” she notes, “the number of employed Detroiters fell by nearly 55 percent,” driving down city tax revenues. As a result, Detroit had less to spend on basic services, meaning that residents could no longer count on “street sweeping, reliable garbage collection, and working streetlights.”

While these snapshots provide readers an emotional connection to Kirshner’s subjects, the author buttresses her points with statistics that reveal Detroit’s dire realities. “Between 2000 and 2012,” she notes, “the number of employed Detroiters fell by nearly 55 percent,” driving down city tax revenues. As a result, Detroit had less to spend on basic services, meaning that residents could no longer count on “street sweeping, reliable garbage collection, and working streetlights.”

In 2014 alone, according to Kirshner, 115,000 locals risked losing their homes to tax foreclosure. Detroit had “five times fewer jobs than its suburbs,” but even those faraway jobs offered little opportunity to rise out of poverty: “About 40 percent of commuters [to the suburbs] had positions that paid less than $15,000 per year.” These depressed conditions take a predictable toll on health. “Life expectancy in the city ranked below that of Russia and North Korea,” Kirshner writes.

As they cling to dilapidated houses and suffer inefficient public transportation to reach low-paying jobs, these citizens suffer one degradation after another. Rising utility rates and property taxes wreak havoc on their household budgets. They need cars to get to work but can’t afford automotive insurance. They clean up vacant lots in their neighborhoods only to have vandals spray paint abandoned houses or gangs fire bullets through their windows. Kirshner blames the blight on outside investors who buy cheap properties and squeeze rents out of locals but do no maintenance and fail to pay property taxes, leaving innocent renters vulnerable to eviction.

In her observations of Detroit, Kirshner identifies a disturbing pattern, wherein a small number of private investors profit from municipal decisions on development, but the risk is subsumed by the general public, often at the cost of services to the most needy. Michigan offered Quicken Loans $50 million in incentives to move their headquarters to downtown Detroit, but the deal was structured so that the construction would do little to revitalize Detroit. “All the revenues from the projects, even indirect revenues, would flow to developers,” Kirshner notes.

If making the rich richer had a measurable trickle-down effect, then public subsidies for private development would make sense. But, as Kirshner points out, tax subsidies have the reverse effect, reducing municipal budgets and thereby “diminishing the funding available for education and for services like transportation and training.” Broke is not an optimistic book, but it makes a strong case for caring about the fates of the resilient citizens of Detroit, and not just because we sympathize with their plight. “Their future,” Kirshner writes, “holds a mirror to America’s.”

Sean Kinch grew up in Austin and attended Stanford. He earned a Ph.D. from the University of Texas. He now teaches English at Montgomery Bell Academy in Nashville.