An Emotional Realist

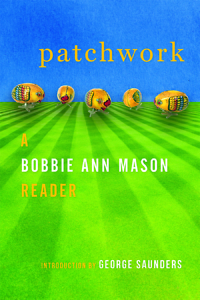

Patchwork surveys decades of Bobbie Ann Mason’s fiction, nonfiction, and interviews

The Lake District of England had Wordsworth. Concord, Massachusetts, had Thoreau. Western Kentucky has Bobbie Ann Mason, whose writing immortalizes the lovely, grim, and mundane ways of life in her native region. The proof is in Patchwork, which brings together short stories, novel excerpts, nonfiction, and interviews from the past thirty-five years.

It’s an exhilarating trip through Mason’s career, starting with three stories from her 1982 debut collection, Shiloh and Other Stories, which won the PEN/Hemingway Award. It includes chapters from the 1985 novel In Country (later a movie starring Bruce Willis that was filmed in Mason’s hometown); the 1993 novel Feather Crowns, inspired by the real-life quintuplets born on a farm near Mason’s own birthplace; and her 1999 memoir, Clear Springs, a Pulitzer Prize finalist.

Patchwork also places Mason’s fiction and nonfiction in revealing juxtaposition. A chapter from her novel The Girl in the Blue Beret is followed by a nonfiction account of the French resistance heroine of World War II on which the novel was based. In 2000, Mason reported for The New Yorker about the local reaction to a radioactive-waste calamity at a plant in Paducah, Kentucky. That piece, called “Fallout,” is followed by a chapter from her 2005 novel, An Atomic Romance, in which an outdoorsman camping near such a plant encounters “eerie blue flames” that flicker on metal scraps in the rain “like a gas fire on artificial logs.” In both, the border that people cross between the natural world and environmental disaster is porous.

“These stories will last,” Raymond Carver wrote in 1982 about Shiloh, and he was right. Three decades have not diminished the power of “Offerings,” “Shiloh,” and “Third Monday,” all included in Patchwork. In the small communities of these tales, loneliness and isolation coincide with the invasive nearness of family members. Characters hide their smoking and drinking habits from prying loved ones. Even the end of a marriage is under wraps: “I don’t know how long I can keep up that night-shift lie,” Sandra tells her mother in “Offerings.” In “Third Monday,” a woman sees “the man she cares about” once a month at a fairgrounds flea market—she suspects he “could have a wife somewhere” but doesn’t ask. A baby’s death defines a disintegrating marriage in “Shiloh,” but the couple can’t talk about it: “They sometimes feel awkward around each other, and Leroy wonders if one of them should mention the child.”

“These stories will last,” Raymond Carver wrote in 1982 about Shiloh, and he was right. Three decades have not diminished the power of “Offerings,” “Shiloh,” and “Third Monday,” all included in Patchwork. In the small communities of these tales, loneliness and isolation coincide with the invasive nearness of family members. Characters hide their smoking and drinking habits from prying loved ones. Even the end of a marriage is under wraps: “I don’t know how long I can keep up that night-shift lie,” Sandra tells her mother in “Offerings.” In “Third Monday,” a woman sees “the man she cares about” once a month at a fairgrounds flea market—she suspects he “could have a wife somewhere” but doesn’t ask. A baby’s death defines a disintegrating marriage in “Shiloh,” but the couple can’t talk about it: “They sometimes feel awkward around each other, and Leroy wonders if one of them should mention the child.”

People in Mason’s stories are not big talkers, but they are distinguished by the way they say things. Mason made a conscious study of the language of her parents and grandparents on the small dairy farm near Paducah where she grew up. Her approach is admiring and affectionate, not anthropological. Her father once described a dog running in circles as “cuttin’ didoes.” When Mason asked him what the phrase means, he told her it means the dog is happy. “But what does the expression come from?” she asked. “Well, it just means he’s cuttin’ didoes,” he answered. This vibrant language was an inheritance: “With words we defy oblivion,” she writes.

Mason’s stories witness the twilight of rural life with a slow, artful accretion of day-to-day detail. In “Wish” from Love Life, she describes what’s on the plate of leftovers a widower gets from his sister after Sunday dinner, what time he finished watching a nature special on grizzly bears, and also his resentment of his late wife for moving him to a “brick box” in town: “He had loved their old place, a wood-frame house with a porch and a swing, looking out over tobacco fields and a strip of woods.” Now he watches speeding traffic from concrete steps.

But Mason doesn’t treat the work a farm requires as a romance—relentless labor takes a toll on a family. Her own dog Rags was killed on the highway when she was ten, “smashed flat, and nobody bothered to remove his body,” she writes in “The Family Farm.” “For a long time it was still there when we went to town-a hank of hair and a piece of bone. It became a rag, then a wisp, then a spot. It’s hard to explain the indifference of the family in this matter, for my heart ached for Rags.” She assumed “they were behind on the spring planting or perhaps the fall corn-gathering. There was always something.”

George Saunders, who won a 2017 Booker Prize for Lincoln in the Bardo, wrote the introduction for Patchwork: “Bobbie Ann Mason is a strange and beautiful writer indeed, and if she is a realist, she is that best kind of realist: an emotional realist,” he observes. For readers already devoted to Mason’s work, Patchwork will be a happy reminder of its depth and breadth. For those who don’t know her yet, here’s a great introduction.

Peggy Burch was books editor at The Commercial Appeal in Memphis for ten years, and she also worked as a deputy metro editor and Arts & Entertainment editor for the newspaper. She is a graduate of the Newhouse School of Public Communications at Syracuse University and holds a master’s degree in English literature from the University of Mississippi.