An Illuminated Mind

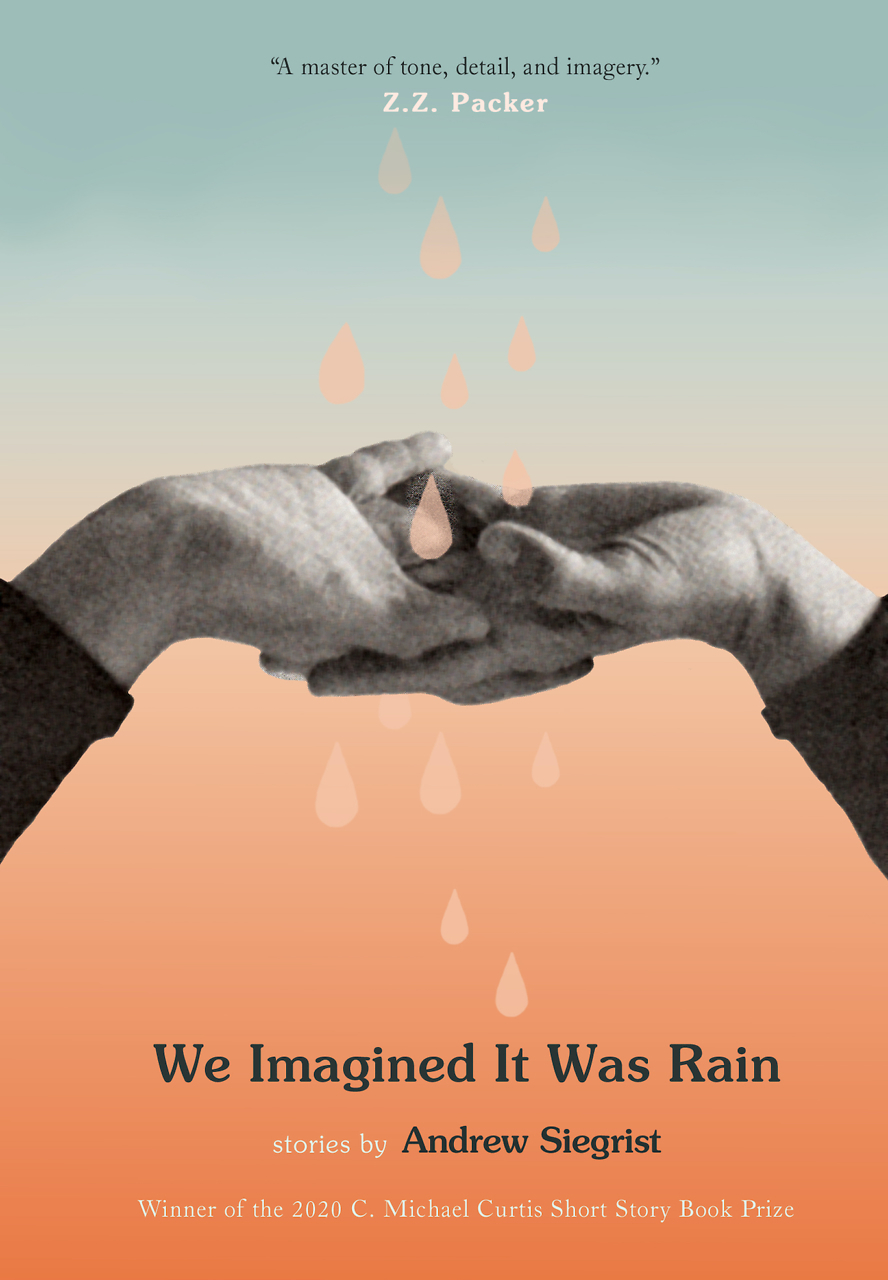

Oblivion Banjo surveys the long career of poet Charles Wright

Oblivion Banjo, the new collection from former U.S. Poet Laureate Charles Wright, offers the first comprehensive survey of one of the major bodies of work in American poetry. Wright was born in the West Tennessee community of Pickwick Dam in 1935 and spent most of his childhood in Kingsport. A stint in the U.S. Army took him abroad to Italy, among other places, where he found inspiration to write poems. He’s been recognized with most of the major awards and distinctions in the poetry world, including the Pulitzer Prize, the National Book Award, and the Bollingen Prize.

Oblivion Banjo brings together the poet’s own selection of the work he wants to preserve from a writing career that spans nearly half a century. Wright has been recognized for being worldly, even cosmic, in his subject matter, which makes the persistence of Tennessee settings in his work striking and purposeful. Tennessee locations and happenings are present from the earliest of Wright’s individual volumes, Hard Freight (1973), to the most recent, Caribou, published in 2014. The Tennessee poems resonate especially because they are some of Wright’s most personal writing and reveal more of his background and family life than poems set in other locations.

For instance, in the long poem I think of as his signature piece, “The Southern Cross” (from the 1981 volume of the same title), the speaker relates a memory from earliest childhood:

All day I’ve remembered a lake and a sudsy shoreline,

Gauze curtains blowing in and out of open windows all over the South.

It’s 1936, in Tennessee. I’m one

And spraying the dead grass with a hose.

The curtains blow in and out.

And then it’s not. And I’m not and they’re not.

This poem resists the nostalgia of continuity, and the speaker seems to distrust his own recollections at times, indicating how selective memory can be and how we often want to create a story line where one does not exist. “The Southern Cross” takes us to different points in time and across the world to Italian gardens, English cemeteries, the coastline of Ischia, and summer “in the high Montana air” before circling back to the hills above Kingsport and finally to the place of origin, remembered in the poem’s final section as such:

Pickwick was never the wind….

It’s what we forget that defines us, that stays in the same place,

And waits to be rediscovered.

Somewhere in all that network of rivers and roads and silt hills,

A city I’ll never remember,

its walls the color of pure light,

Lies in the August heat of 1935,

In Tennessee, the bottomland slowly becoming a lake.

While Charles Wright has been a beloved poet for decades, his poetry may still feel remote to readers new to his work. Reading Wright’s poems could be thought of as the process of observing an illuminated mind in conversation with the people, places, books, and beliefs that have made an impact upon it. There’s no need to know the Bible, or Dante, or the ancient Chinese poets as extensively as Charles Wright knows them to comprehend how much they have shaped his experience.

While Charles Wright has been a beloved poet for decades, his poetry may still feel remote to readers new to his work. Reading Wright’s poems could be thought of as the process of observing an illuminated mind in conversation with the people, places, books, and beliefs that have made an impact upon it. There’s no need to know the Bible, or Dante, or the ancient Chinese poets as extensively as Charles Wright knows them to comprehend how much they have shaped his experience.

The brilliance of Wright’s achievement lies in how seamlessly he integrates such cultural monuments with everyday occurrences that almost anyone can relate to, like sitting in the backyard and watching clouds pass overhead, or reflecting on one’s travels, or simply remembering moments from childhood that refuse to be forgotten. Oblivion Banjo reveals the evolution and expansion of a singular voice, a singular vision, through the stages of a closely observed and considered life.

Though I have studied Charles Wright’s poetry since I was an undergraduate at the University of Tennessee, at the prescient suggestion of the late Dr. Arthur Smith, I confess I was still taken aback by the power of reading these poems all together. I find a mystery in them that reminds me of Emily Dickinson, a glorious fecundity to the language that makes me think of Gerard Manley Hopkins, and a painterly attention to the smallest movements and stillnesses that brings Wallace Stevens continually to mind.

Yet Charles Wright has created his own style, a characteristic use of lineation and diction that no regular reader of poems could mistake for any other poet. His manner of delivering and developing his meditations is truly original. Oblivion Banjo offers moments of harrowing existential dread, luminous beauty, and wry humor, and these qualities combine with the title to suggest that eternity is a reality beyond conception but there is no reason not to face it with a bit of hopeful music.

Jesse Graves is the author of four poetry collections, including the forthcoming Merciful Days. His work received the James Still Award for Writing about the Appalachian South from the Fellowship of Southern Writers. Graves teaches at East Tennessee State University, where he is poet-in-residence and associate professor of English.