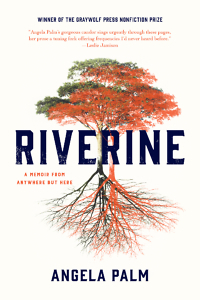

An In-Between Life

Angela Palm’s memoir, Riverine, reckons with the lingering effects of growing up in Nowhere, Indiana

The subtitle of Angela Palm’s Riverine: A Memoir of Anywhere But Here suggests a tale of disappointment and sorrow, of striking out from a dead-end hometown. Though her story includes its share of heartbreak, Palm also expresses fond memories of her birthplace: not even a town but a blank area between two hamlets in northern Indiana—corn country along the Kankakee River.

Palm was raised in a culture of violence. Her father had an explosive temper, though he also protected his daughter from the “drunks and vagabonds” who threatened her innocence. Corey, the boy next door who stole Palm’s heart when she was a child, got sent to prison for a terrible crime. Her Uncle Pat went to prison for shooting his boss. At her first visit, Uncle Pat pointed out Mike Tyson, in the same institution for rape, who greeted Palm and her brother and entertained them with Bugs Bunny jokes. Palm includes these anecdotes to humanize the crimes that darkened her young life. “Mike Tyson had done bad things,” Palm writes. “So had Corey, so had Uncle Pat. I didn’t hate any of them.”

The other main thread of Palm’s memoir follows her path to becoming a writer. A good student and passable artist, she experimented with a number of professions before pursuing her interest in storytelling. Based on the evidence of Riverine, winner of the Graywolf Press Nonfiction Prize, Palm has found a vocation that suits her talents. Her prose moves swiftly, interspersing illustrative detail and personal insight. In the first chapter she explains why, having grown up in unmarked territory, she still feels “truly comfortable” inhabiting a map’s undefined spaces, “the square half inch of yellow paper between pink dots. The in between here and there, where damp moss grows and people sometimes live in tepees.”

In Palm’s case, emerging as a writer and making sense of Corey’s crime amount to the same quest. She devotes large sections of the book to walking her life back to the moment when it was torn apart. “Bifurcation comes to mind when I think of Corey,” Palm says. “As in the shape made by the branching of the Kankakee River and the Illinois River. As in me going one way and Corey going another.” When she heard about the violent crime that sent Corey to prison for life, she felt herself “divide further. That part of me that had held fast to my idea of him—so much better than he really was, so out of touch with who he was becoming—split again and again.”

In Palm’s case, emerging as a writer and making sense of Corey’s crime amount to the same quest. She devotes large sections of the book to walking her life back to the moment when it was torn apart. “Bifurcation comes to mind when I think of Corey,” Palm says. “As in the shape made by the branching of the Kankakee River and the Illinois River. As in me going one way and Corey going another.” When she heard about the violent crime that sent Corey to prison for life, she felt herself “divide further. That part of me that had held fast to my idea of him—so much better than he really was, so out of touch with who he was becoming—split again and again.”

Riverine remains focused on the particularities of Palm’s personal growth and makes no claim to universality. Palm reached puberty early, a change that brought unwanted—and isolating—attention: “The other girls my age still looked like children; the boys snapped my bra and called me names,” she writes. “I was an island of growth and hormones.” At eleven she could already “feel the attention of boys and men upon me, their gazes warm and penetrating as the sun.” A different sort of memoir might have devoted more space to depicting how Palm’s premature sexualization affected her personality; for Palm it’s merely background information for larger questions regarding fate and contingency.

As she recounts her journey—to college at a nearby campus through her dissipated twenties and into marriage—she continually circles back to the question of psychological origins: how many of her problems (obsessiveness, paralyzing fear, recklessness) can be traced to growing up “in an old riverbed” with “a bloodline that ran brown like its water”? Can she re-make her identity as easily as she changes boyfriends and hair color, or is there a riverine component to her character that cannot be washed away? Engineers have straightened the Kankakee, but it regularly floods, returning to its original marshland curves, “as if the very ground itself had called it back home.” Is she similarly destined? “Like rivers, people are always folding back on themselves,” Palm writes. “Contradicting themselves. Pulling off a bluff even as they try to begin anew, and then collapsing back onto the past.”

Palm infuses her memoir with a mature wisdom that ultimately calms the furies unleashed by childhood trauma. In the end she is able to see the truth buried beneath her muddy memories.

Sean Kinch grew up in Austin and attended Stanford. He earned a Ph.D. from the University of Texas. He now teaches at Montgomery Bell Academy in Nashville.