As American As Apple Pie

Tony Horwitz talks with Chapter 16 about the complicated legacy of abolitionist John Brown

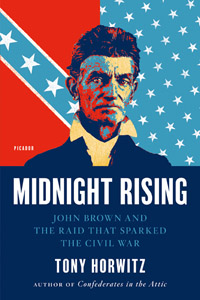

Tony Horwitz’s Midnight Rising: John Brown and the Raid that Sparked the Civil War tells the gripping story of John Brown, the abolitionist who in 1859 organized and led a raid on the federal armory at Harpers Ferry in an attempt to further the cause of emancipation of the American slave population. Although Brown’s attack was a failure, his actions did succeed in widening the schism between North and South that would lead to the outbreak of Civil War. In Horwitz’s telling, the figure of John Brown is as fascinating as his deeds. Brown was a deeply religious man for whom abolition, even by violent means, was a moral imperative.

Tony Horwitz is the bestselling author of A Voyage Long and Strange, Blue Latitudes, Confederates in the Attic, and Baghdad Without a Map. He is also a Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist who has worked for The Wall Street Journal and The New Yorker. Horwitz lives in Martha’s Vineyard with his wife, Pulitzer Prize-winning novelist Geraldine Brooks, and their two sons. In advance of his appearance at Nashville’s Southern Festival of Books, he recently answered questions from Chapter 16 by email:

Chapter 16: Midnight Rising is not your first book about the Civil War. You also wrote the bestselling Confederates in the Attic: Dispatches from the Unfinished Civil War (Pantheon, 1998), in which you explore the thrall in which Americans, especially in the South, continue to hold the war. I’m curious about how you developed your interest in this period. And what made you decide to pursue John Brown?

Chapter 16: Midnight Rising is not your first book about the Civil War. You also wrote the bestselling Confederates in the Attic: Dispatches from the Unfinished Civil War (Pantheon, 1998), in which you explore the thrall in which Americans, especially in the South, continue to hold the war. I’m curious about how you developed your interest in this period. And what made you decide to pursue John Brown?

Tony Horwitz: I was a Civil War nerd almost from birth and rediscovered my boyhood obsession when my wife and I settled in rural Virginia in the 1990s. I felt surrounded by the War—battlefields, fights over memory, crazed reenactors—and that’s what led me to write Confederates in the Attic. While researching the book, I visited Harpers Ferry, only fifteen miles from my home, but it didn’t dawn on me to write about John Brown and his raid until I’d moved a decade later to New England. Go figure.

One reason I was drawn back to this period is that I’d always dwelled on the Civil War proper, from 1861 to 1865, without really understanding how and why the conflict came about. John Brown’s Raid seemed like a good place to start. Also, it’s a writer’s dream, a tense, sweaty drama with an unbelievable cast of characters—not just Brown but Lincoln, Robert E. Lee, the Transcendentalists, Frederick Douglass, John Wilkes Booth, and many others.

Chapter 16: In the popular imagination, the historical figure of John Brown has often been reduced to the heroic abolitionist that Henry David Thoreau exalted as Brown was being martyred in Harper’s Ferry. But as becomes painfully clear in your book, the real John Brown was far more complicated than the historical myth. How did the John Brown you discovered through your research compare to the Brown you thought you knew before you undertook the project? What surprised you most about the real John Brown?

“For an insurrectionist, he was surprisingly conventional in many respects: a family man, devout Christian, and American on the make who had a long career as a farmer, tanner, and wool merchant before he took up arms.”

Horwitz: Before writing this book, most of what I knew about Brown came from the little I’d learned in junior high. I also knew the songs about him and recalled my childhood visit to the John Brown Wax Museum in Harpers Ferry. He seemed a spooky figure, and I imagined him as a crazed and alienated man, a lone gunman. So it surprised me to learn that he was actually part of a full-blown conspiracy that drew support from prominent, wealthy Northerners and included dozens of young fighters who weren’t much different from men who later fought in the Civil War. Also, for an insurrectionist, he was surprisingly conventional in many respects: a family man, devout Christian, and American on the make who had a long career as a farmer, tanner, and wool merchant before he took up arms.

Chapter 16: One of the interesting things you stress in the book is the degree to which Harpers Ferry, though a dismal failure tactically, succeeded in stoking the existing tensions between North and South, hastening the outbreak of war. And after the war was over, the extension of the rights of citizenship to blacks followed—at least initially—the path Brown had helped to blaze. But Brown’s influence doesn’t end with the emancipation of slaves and the growth of civil rights. One later group that paradoxically traced its lineage to John Brown—and even farther back to the Sons of Liberty—was the Black Legion, a paramilitary offshoot of the KKK based in the Midwest in the 1930s. The Black Legion drew inspiration from John Brown’s use of political violence, even though the group was itself pursuing a white supremacist agenda completely contrary to everything John Brown stood for. Given some of these conflicting elements, what do you think the legacy of John Brown and Harper’s Ferry is? Or are there multiple legacies?

Horwitz: I can’t think of another figure in our history that has spawned such a diverse group of admirers. Brown was embraced by late-nineteenth-century anarchists, by early civil-rights activists, by Black Panthers, and by the Weathermen. Yet he was also cited as a model by Timothy McVeigh and by anti-abortion bombers. Brown speaks to militants of all stripes and eras who believe that God, individual conscience, or their urgent quest for justice trumps man-made law. So he set a powerful, if potentially dangerous precedent. That’s one reason I’m so fascinated by the man. There’s no easy way to feel about him. The novelist Truman Nelson called Brown the stone in the shoe of American history, this troubling presence we can’t shake or ever feel comfortable with. I think we should embrace that discomfort and explore the hard questions that Brown and his actions raise.

Horwitz: I can’t think of another figure in our history that has spawned such a diverse group of admirers. Brown was embraced by late-nineteenth-century anarchists, by early civil-rights activists, by Black Panthers, and by the Weathermen. Yet he was also cited as a model by Timothy McVeigh and by anti-abortion bombers. Brown speaks to militants of all stripes and eras who believe that God, individual conscience, or their urgent quest for justice trumps man-made law. So he set a powerful, if potentially dangerous precedent. That’s one reason I’m so fascinated by the man. There’s no easy way to feel about him. The novelist Truman Nelson called Brown the stone in the shoe of American history, this troubling presence we can’t shake or ever feel comfortable with. I think we should embrace that discomfort and explore the hard questions that Brown and his actions raise.

Chapter 16: Are there differences in the ways the South and the North remember John Brown and Harper’s Ferry?

Horwitz: I’ve spoken about this book fifty or so times, in both North and South, and haven’t found a strong regional divide in the memory of Brown. Back in the day, white Southerners had a more demonic image of Brown than Northerners, but over the past fifty years or so, Americans have learned about him from much the same textbooks. The larger divide is racial. Brown has long been an icon in the African-American community, North and South, and in my experience, he continues to be viewed much more favorably by blacks than by whites.

Chapter 16: Part of what makes Harper’s Ferry so fascinating is the uncomfortable contradictions it raises. On the one hand, we can admire the resolve and dedication of Brown and his followers to die for a cause that we now consider to have been honorable. Yet, even at the time, many of his fellow abolitionists disapproved of Brown’s recourse to violence. Since Harper’s Ferry, we’ve seen similar violent analogues. I mentioned the Black Legion already, but a more recent comparison would be to the militia movement of the 1990s, which culminated in the bombing in Oklahoma City in 1995. As you mention in the book’s prologue, “Viewed through the lens of 9/11, Harpers Ferry seems an Al Qaeda prequel: a long-bearded fundamentalist, consumed by hatred of the U.S. government, launches nineteen men in a suicidal strike on a symbol of American power. A shocked nation plunges into war.” As a historian, do you view Harper’s Ferry as part of a historical continuum of armed insurrection against the government?

“Brown reminds us that violence is indeed as American as apple pie.”

Horwitz: Hmmm, we’re drawing together some pretty disparate folk here and I’m wary of generalizing. But I do think Brown reminds us that violence is indeed as American as apple pie. He was the grandson of Revolutionary War officers and felt strongly that he was continuing their fight against injustice and tyranny—in essence, completing their mission. Brown repeatedly said that his guideposts were the Declaration of Independence and the Golden Rule. So in his fundamental beliefs he wasn’t from another planet, which is one reason he spoke so powerfully to other Americans in his court speeches and prison letters.

But I think he has to be viewed in the specific context of his times, rather than as part of a “continuum of armed insurrection against the government.” His hatred of government had little or nothing in common with the militia movement or others you cite. He hated the state because he saw it as a servant of the “Slave Power.” If I’d liken his act to any other in our history, it would be Nat Turner’s slave rebellion in Virginia in 1831.

Chapter 16: Do you have any plans for future books related to the Civil War?

Horwitz: Not currently. There’s no shortage of books on the subject, so I’d only write one if I felt I had something fresh to say. And each of my books tends to be a departure from the last. But I’ll never say never to the Civil War era.

Tony Horwitz and Christopher Hebert will appear at the twenty-fourth annual Southern Festival of Books, held October 12-14 at Legislative Plaza in Nashville. Hebert will discuss his novel, The Boiling Season, on October 12 at 1 p.m. in Conference Room 1A of the Nashville Public Library. Horwitz will discuss Midnight Rising on October 14 at noon in the Nashville Public Library Auditorium. All festival events are free and open to the public.