Beyond Catharsis

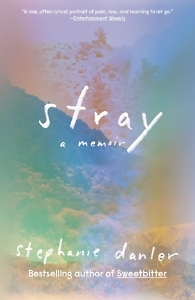

Stephanie Danler’s memoir disrupts the usual narrative structures found in stories of addiction

One of my favorite scenes in Stephanie Danler’s memoir, Stray, occurs when Danler is sitting in a writing workshop, sharing the early pages of what would become her bestselling novel, Sweetbitter. A man in her workshop tells her the pages are good but that he hopes the novel won’t be “just a love story.” Danler quickly reassures him the novel is also about Big Ideas, but later she wonders, “Wait. What is just a love story?”

In the same way a love story is never just a love story, Stray, which largely focuses on the effects of growing up in a family destroyed by addiction and abuse, is not just a book about trauma. It’s also a book about family. Which is to say that Stray, in its way, is also a love story.

Love for family and friends suffuses Stray, wends its way even through the most difficult pages. But that doesn’t mean readers should expect, or want, a sentimental sense of release. “There is nothing falser to me than a story that ends with catharsis,” Danler writes. Stray makes efforts to disrupt and interrogate a narrative structure — perhaps one particularly prevalent in memoirs dealing with the course of addiction — that ends with any kind of clear solution or release. In part, this interrogation occurs through Danler’s frequent observations around the nature of talking and writing about being a child who has grown up around parental substance abuse. “No one wants to look directly at the trauma itself,” she notes, “only the shapes it makes.”

Stray may eschew a linear shape in its storytelling, but it certainly is never shapeless. It’s broken into three sections: one focused primarily on Danler’s mother, one on her father, and one on the married man with whom she is carrying on an affair. (The sections are titled, respectively, Mother, Father, and Monster.) In addition, different scenes are labeled with and anchored by the geographical setting in which they mostly take place. Whether Danler is visiting the hospital after her mother suffers a brain aneurism, giving a reading during her book tour for Sweetbitter, in the back of a cab with the Monster, or hiking with the man who is, for much of the memoir, labelled “the Love Interest,” the geographical location of the action is always clear — a grounding mechanism that feels especially poignant during scenes when Danler clearly felt, in the moment, utterly groundless.

Danler’s account spans a fair amount of geographical space, and her descriptions of geological features in California are among the book’s loveliest moments, in part due to the way these moments often coincide with a slowly growing romance between Danler and the Love Interest. The Love Interest’s knowledge about the environment around them seems to grant Danler a new lens for noticing and describing, for being present in the state of her birth in a different way. The map of Los Angeles-area freeways at the book’s opening takes on new meaning as Stray continues.

Danler’s account spans a fair amount of geographical space, and her descriptions of geological features in California are among the book’s loveliest moments, in part due to the way these moments often coincide with a slowly growing romance between Danler and the Love Interest. The Love Interest’s knowledge about the environment around them seems to grant Danler a new lens for noticing and describing, for being present in the state of her birth in a different way. The map of Los Angeles-area freeways at the book’s opening takes on new meaning as Stray continues.

Despite the memoir’s many markers of place, however, I sometimes was briefly disoriented as to where I was in its kaleidoscopic and occasionally blurry timeline. Still, part of Danler’s project here seems to be blurring boundaries. “It’s through boundaries that we construct ourselves, say, Here is where you end and I begin. However, while boundaries are powerful, they’re unfortunately not solid,” she writes. “They are made in the imagination, and there are inherent flaws in arming oneself for battle in our fantasies. What is shocking isn’t that we have lived through the traumas of our lives. The miracle is that we are still remotely permeable.”

And what to do once you do allow for those moments of permeability, for vulnerability and connection? It’s not exactly some kind of crescendo of catharsis, but Danler does advocate for the power of presence and care for what’s before us in the present moment: “We don’t receive the things we want because we deserve them. Most of the time we get them because we are blind and lucky. It’s in the act of having, the daily tending, that we have an opportunity to be deserving. It’s not a place to be reached. It is a constant betwixt and between.”

Stray’s moments of greatest power are achieved in the instances where Danler unflinchingly describes and details those in-between borderless spaces, the places where there are opportunities for tending, for care — and, maybe, for love stories.

[This article originally appeared on June 3, 2020.]

Lee Conell is the author of the novel The Party Upstairs, forthcoming from Penguin Press this July. She is also the author of Subcortical, a story collection, which won the Story Prize Spotlight Award. A 2020 National Endowment for the Arts Creative Writing fellow, she has taught fiction writing at Vanderbilt University and the University of the South. She lives in New York City.