Big Man on Campus

James Dickey in the classroom

“He died from drinking a bottle of Lysol,” James Dickey said.

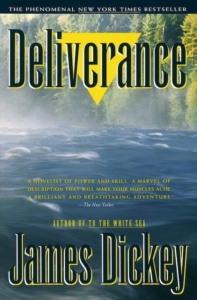

The big man paused to stare at us, eyes bright as he smiled the half-smile of the Sheriff from his scene in Deliverance. As though leaning down to Jon Voight’s car window to ask about life jackets, Mr. Dickey delivered his best line of the day: “The ecstatic, ebullient types all kill themselves, one way or another.”

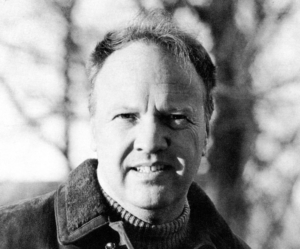

It was October 27, 1983, 10 minutes into his lecture on Vachel Lindsay, halfway into my first semester of graduate school at the University of South Carolina. I had become enthralled by Mr. Dickey’s dramatic manner of teaching ENGL 602, Survey of 20th Century British and American Poetry. At that point he was firmly “Mr. Dickey” in my mind, though the older grad students spoke of him as “Big Jim.” I had seen one slap his back in the hall and call him “Jim,” but it would take months before I screwed up such courage.

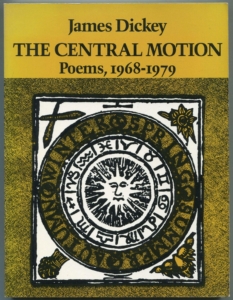

I had come to South Carolina by mistake. When an undergraduate professor suggested I look into graduate programs for creative writing, I asked where I should go. He mentioned Iowa, USC, and a few other schools. Naïve Southerner that I was, I thought USC meant the home of the Gamecocks. By the time I realized he meant Southern California, the other USC had already offered me a teaching assistantship and fellowship, so there I was. In those days I wanted to become a novelist, but Mr. Dickey, author of a bestselling novel and wildly successful screenplay, taught only poetry, which he called in one of his book titles “the central motion.” So poetry it was. I signed up for his survey course, the first of three poetry classes I would take from him. Before reading his novel, I had enjoyed several of his poems in a sophomore lit class in 1979. I had no way of knowing that my Norton anthology was one of the last textbooks to include Dickey’s work (or Lindsay’s, for that matter), that James Dickey’s eminence as an American poet had begun to slide simultaneously with his commercial success.

One of Mr. Dickey’s admonitions in Verse Composition, where I would spend an entire semester conceiving and revising a single long poem, was “Never throw anything away.” He was 62 that year — my age as I write these words — and to the extent I can do so while preserving marital bliss, I have followed his advice. When Gordon Van Ness (a fellow student in my first Dickey class) recently stirred my memory by publishing his literary biography, James Dickey: A Literary Life, I was able to dig from an old filing cabinet three notebooks used in Dickey’s classes. Within them I found notes on Vachel Lindsay, among other names: Dickinson, Crane, Williams, Auden, Yeats, Robinson, Jarrell, Jeffers, and more.

Five minutes before class, Mr. Dickey would lurch into the room toting a heavy leather satchel or occasionally a cardboard box. In my memory he was always dressed in a rough leather jacket with fringes, jeans, a chambray shirt open at the neck, and some sort of pendant worn on a leather cord. His stained slouch hat could have been stolen from the Deliverance set. (It recalled the movie line: “I love the way you wear that hat.”) He would sit in a wooden chair at a library table in front of the classroom, placing the hat on one corner. From the satchel or box he would extract a dozen or more books, all connected in one way or another to that day’s poet. He would carefully arrange these around the table for easy reach during the coming lecture, greeting students by name as he did so.

According to my notebook entry from October 27, Mr. Dickey spent the first 15 minutes or so delivering an ad hoc biography of Vachel Lindsay before getting to the poetry itself. “Lindsay’s granddaughter actually enrolled in this class,” he told us, pointing more or less toward me. “Sat right there.”

By then, I realized later, both the granddaughter and Dickey would surely have known that Lindsay’s most famous work, “The Congo,” had been denounced as racist in the poet’s own time and even more so by critics later in the century. Rachel Blau Duplessis wrote that Lindsay, who helped the early career of Langston Hughes and frequently spoke in favor of racial equality, held good intentions, but still achieved a racist result with a poem that “is as much a veiled justification for lynching as a criticism of it.”

By then, I realized later, both the granddaughter and Dickey would surely have known that Lindsay’s most famous work, “The Congo,” had been denounced as racist in the poet’s own time and even more so by critics later in the century. Rachel Blau Duplessis wrote that Lindsay, who helped the early career of Langston Hughes and frequently spoke in favor of racial equality, held good intentions, but still achieved a racist result with a poem that “is as much a veiled justification for lynching as a criticism of it.”

Rather than address the racism, Mr. Dickey began relating Lindsay’s childhood, as he did with most poets, in stark terms: “Born 1879 in Springfield, Illinois. Father was a doctor. Mother was a religious fanatic. The boy was a half-cracked artist and poet who thought of himself as a ‘Christian cartoonist.’” He explained the roots of Lindsay’s very public style of recitation, describing how in 1912 the penniless poet walked from Illinois to New Mexico, begging at farmhouses with poems “to be traded for bread.”

“Imagine walking up to a farmer today to make that bargain,” Mr. Dickey said, shifting into a more redneck version of his refined Southern drawl. “Well now son, that poem better be a long ‘un, and it got-dam-well better rhyme.”

He spoke with something approaching awe of the huge crowds Lindsay drew to performances at the height of his career, calling them “the largest audience for any poet before or since.” “The Congo,” he pronounced, is a poem that makes “no sense at all” except when performed. He then gave the class a door-rattling example of the poem’s refrain: “Boomlay, boomlay, boomlay, BOOM!”

Later I would discover that Dickey had published extensive criticism on each of the poets he taught us. He had reviewed, for example, Letters of Vachel Lindsay in The New York Times (NYT) four years before. As the class moved from early to mid-20th century, in addition to writing about them he seemed to know them all personally. Invariably he would describe how they behaved when drunk, a condition in which some fared better in Mr. Dickey’s estimation than others. Yet, as Gordon reports in James Dickey: A Literary Life, our teacher’s anecdotes were often unverifiable, examples of what he terms Dickey “creating his own myth, not ‘lying.’”

His personal stories about living poets were sometimes confirmed by those poets in later memoirs; others cannot be found in any published source. I once spent weeks fruitlessly chasing down a Dickey story about William Carlos Williams, with whom he had corresponded extensively, regarding the circumstances leading to the composition of Williams’ minimalist masterpiece, “The Red Wheelbarrow.” Years later, after Google became a thing, I searched again. No luck. Eventually I decided that the story was so good it ought to be true. In any case, most of us students fell sway to the myth.

In 1983, Gordon, a PhD candidate, was already married with children. His thin face dominated by thick-lensed glasses, he seemed much older and more learned than my fellow students, already the professor that many of us would ultimately become. He matriculated at South Carolina specifically to study under James Dickey. The literary biography, 40 years in the making and authorized by the late poet and his family, is the culmination of a life’s work that began with his master’s thesis at the University of Richmond before he started doctoral work the same semester I began working on my master’s degree. Gordon’s extensive publications would grow to include five books on Dickey that preceded his masterwork.

In spite of his seriousness as a student (at least when compared to me), I found Gordon fun to talk to. We discussed novels, films, teenage adventures, and many other things. He and I founded a writers group of Dickey students that included several eventually published authors, among them Ken Autrey, Thom Dabbs, Alice Cabiness Banks, F. Brett Cox, and Margaret Renkl — a poet who became the founding editor of Chapter 16 and now a popular NYT columnist. Besides sharing and discussing our works in progress, members of our group took turns hosting poker games and potluck dinners. Sometimes we hung out at a popular student bar in Columbia’s Five Points neighborhood, where we would argue literary topics with all the pomposity and grandeur that only earnest grad students can muster.

In spite of his seriousness as a student (at least when compared to me), I found Gordon fun to talk to. We discussed novels, films, teenage adventures, and many other things. He and I founded a writers group of Dickey students that included several eventually published authors, among them Ken Autrey, Thom Dabbs, Alice Cabiness Banks, F. Brett Cox, and Margaret Renkl — a poet who became the founding editor of Chapter 16 and now a popular NYT columnist. Besides sharing and discussing our works in progress, members of our group took turns hosting poker games and potluck dinners. Sometimes we hung out at a popular student bar in Columbia’s Five Points neighborhood, where we would argue literary topics with all the pomposity and grandeur that only earnest grad students can muster.

In the fall of 1983, Mr. Dickey traveled extensively on the lecture circuit, resulting in occasional canceled classes, and he was still drinking then, at least occasionally. I learned to read the degree to which he arrived to class unshaven as an indicator of how his previous night — or lecture junket — had gone. My notebook entry for the day on Frost, near the end of the semester, begins with the underlined statement, “Pretty bad off today.” I noted in a side margin, “Dickey reminds me of my grandfather. Drunk whiskers and good stories of poets or of mules, what is the difference?” In the margin at the top, I wrote: “It’s legit, I suppose. D Advises, ‘Fuck your grades. Read what you want.’” (This still seems legitimate advice, although I might not share it with my own students.)

That same day I starred a notation that the class was invited to “Xmas party at D’s house on Lake Katherine, Saturday, December 3, 7 to 10 p.m. or later. Food and drink provided.” The thing I remember most about my first visit to his house is that virtually every wall was lined with floor-to-ceiling bookshelves, and every book I randomly pulled to examine (five or six before the night became hazy) included a warm personal notation from the author, casually addressed to “Jim.” I wondered, I think for the first time, what sort of life could lead one to possess such a library.

Dreams were important, Mr. Dickey told us on several occasions. Under his direction we kept dream journals for his Verse Composition class as we worked toward a topic. One day after class I approached him to share the idea I wished to pursue, on the exploration of a deep Southern cave by an obsessed man. I explained that I had become an active caver as an undergraduate at Florida State University and had since met many individuals who lived to enter chambers never before seen by humans. Caves were a subject I wanted to explore as a writer, just as much as I endeavored to explore them literally.

Mr. Dickey’s eyes lit up. “Caves are fascinating!” He told me about a cave he had once in entered in Georgia with a tight, difficult crawlway. He rattled off the titles and authors of three good books and several poems about caves — none of which I had encountered in my years of reading on the subject. One was a long narrative poem about the caves of England’s Mendip region, by a writer named James Kirkup — about whom he of course shared a personal story and cited a review he had written. Immediately after parting with Jim (as he became for me that day), I found Kirkup’s brief volume The Descent into the Cave buried within the depths of the Thomas Cooper Library.

I flipped through its pages and saw that it was more or less the sort of poem I had in mind to write, and I almost gave up. But Jim’s clear enthusiasm, and the fact that I wanted to write about a very different sort of American cave, one involving solo rope work in deep pits, kept me going. I still have early drafts of the poem, all of which benefitted from Jim’s suggestions.

To recreate exactly the feel of a tight crawlway, I descended the many subfloors of the campus library to a roomful of topographic maps and found and copied the location of a small spring cave that emerged from a limestone ridge in a coastal swamp about an hour east of Columbia. Gordon went with me. Deep in the tick-filled scrub, we encountered actual moonshiners that Dickey might have invented but managed to nod and move along without incident. At the spring in the ridge, we dropped to our bellies to struggle through a wet hole in the rock and press forward in tight gravel beyond daylight. At last we reached a round chamber where we could stand and hurl transformative metaphors at one another across the echoing blackness.

I kept the best ones for the poem.

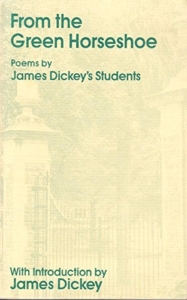

Although I became a journalist and journalism professor — and the world of poetry is undoubtedly better off for it — I nonetheless found myself following his advice in large and small ways throughout my career. What I didn’t realize at the time was that Jim was teaching me not only how to write, but how to teach writing. He was fiercely loyal to his students, as Gordon writes in the biography. Dickey included my cave poem in From the Green Horseshoe, an anthology of work by his students, encouraging me to later write about caves and cavers around the world. In 1996, when I was about to publish Cave Passages, my first book, Dickey wrote a generous jacket blurb, and when I later sent him a finished copy, he wrote an even more generous letter.

Although I became a journalist and journalism professor — and the world of poetry is undoubtedly better off for it — I nonetheless found myself following his advice in large and small ways throughout my career. What I didn’t realize at the time was that Jim was teaching me not only how to write, but how to teach writing. He was fiercely loyal to his students, as Gordon writes in the biography. Dickey included my cave poem in From the Green Horseshoe, an anthology of work by his students, encouraging me to later write about caves and cavers around the world. In 1996, when I was about to publish Cave Passages, my first book, Dickey wrote a generous jacket blurb, and when I later sent him a finished copy, he wrote an even more generous letter.

I thought I lost his letter decades ago but chanced across it as I wrote this essay. “Whatever message I had for you as your teacher, you have,” he wrote, “and have put to use; the best.” He signed the letter, “Jim D.”

As a side gig that I can tie to reading Dickey’s critical works (and to an invitation by Margaret Renkl), I’ve published well over 100 book reviews, often delivering some sort of in-your-face Dickey pronouncement in my lead or as a kicker at the end. I’ve taught writing for over 30 years, and I still delight in spotting a passion in students — any passion whatsoever — and sharing with them good books and articles on that subject, which, thanks largely to the Dickey’s influence, I somehow seem to know. I force students, especially the best writers, to workshop the same piece over and over again. I force myself to do the same.

A final excerpt leaps from my notebook, a momentary digression that I still can hear and see clearly in memory: During his lecture on Lindsay, Mr. Dickey interrupted himself to explain that the theatrical nature of “The Congo” meant — at least back then — that it was often chosen by high school students competing in elocution contests. He had once judged such a contest at the University of South Florida, he related, where a young man took the stage and announced in a very formal manner, “I shall recite Vachel’s Lindsay’s ‘The Congo’ after the manner of Mr. Marlon Brando.”

He then leaned back in his chair like the Godfather at his desk and gave us several lines of the kid doing Brando doing The Godfather doing “Boomlay, boomlay, boomlay, BOOM!”

Everyone laughed, Big Jim Dickey loudest of all.

Copyright © 2022 by Michael Ray Taylor. All rights reserved. Michael Ray Taylor is the author of Hidden Nature. He lives in Arkadelphia, Arkansas, where he is finishing a novel.