Black and White and Red All Over?

Thomas J. Hrach shows how better reporting on race reduced rioting in the 1960s

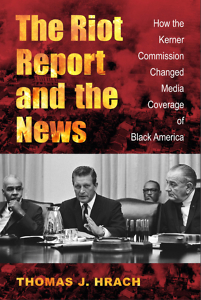

Riots rocked dozens of American cities in the summer of 1967, including Newark and Detroit, leaving dozens dead and hundreds arrested. That July President Lyndon Johnson convened a panel of politicians, labor leaders, civil-rights activists, and business executives to investigate the causes of America’s epidemic of urban violence and to recommend solutions. Officially called the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders, it became known to history as the Kerner Commission, after its chair, Illinois Governor Otto Kerner Jr.

After months of meetings and hearings in cities around the country, the commission issued its report in March 1968. It became an instant bestseller, propelled by controversial conclusions like “Our nation is moving toward two societies, one black, one white—separate and unequal,” which seemed to place the blame for the riots on white society. President Johnson ignored the report, and with Richard Nixon’s victory that fall, it became a footnote, an incisive analysis that few people in politics took seriously.

After months of meetings and hearings in cities around the country, the commission issued its report in March 1968. It became an instant bestseller, propelled by controversial conclusions like “Our nation is moving toward two societies, one black, one white—separate and unequal,” which seemed to place the blame for the riots on white society. President Johnson ignored the report, and with Richard Nixon’s victory that fall, it became a footnote, an incisive analysis that few people in politics took seriously.

But as Thomas J. Hrach, an associate professor of journalism at the University of Memphis, shows in his new book, The Riot Report and the News, the Kerner Commission did, in fact, have an impact—just not where it expected. While public and political attention looked at other parts of the report, the news media zeroed in on Chapter 15, which scored the journalism trade for its lack of racial and ideological diversity. Hrach argues that here the report actually did make a difference, that within a few years newsrooms were rapidly diversifying, with a revolutionary consequence for how news is reported, an effect still felt today.

Chapter 16: By 1967, you note, it was widely believed that news coverage fanned the flames of racial disorder. But you also reveal a problem regarding diversity of staff and viewpoints within the media. How does staff diversity make a difference when it came to coverage?

Thomas J. Hrach: The common belief during the summer of 1967 was that if the news media—TV mostly—would stop reporting on the rioting, it would not spread from city to city. The Kerner Commission report debunked that idea, saying that reporting on rioting does not incite people to become violent. Instead, the report concluded that there was an indirect connection between news reporting and the riots. That indirect connection came because the reporting was superficial and focused only on the aftermath of the rioting.

The report said the news media needed to tell the public that young African Americans turned to violence as an expression of anger over the issues of poverty, racism, segregation, and the lack of education and jobs in the inner cities. The root causes of the problem were never being reported.

Chapter 16: Why did the commission itself decide to tackle the news media? What did the commissioners hope to achieve?

Chapter 16: Why did the commission itself decide to tackle the news media? What did the commissioners hope to achieve?

Hrach: The commission hoped to spark people in the news business—television and newspaper executives mostly—to think about their social responsibility. The idea was to convince the news media that they had as much at stake in solving the problems of America as did the politicians. It is an irony of history that one of the two major long-term outcomes of the Kerner Commission report was on the news media, not on Congress or the politicians. The other major outcome from the report was on how police did a better job responding to rioting.

Chapter 16: It seems like one reason the commission focused on the media was because several were already experienced in working with journalists. Who were they, and what influence did they have?

Hrach: The Kerner Commission had eleven members, and it was carefully constructed to make sure Democrats and Republicans had an equal voice along with representatives of law enforcement, business, and labor. While none of the eleven members were journalists, two had experience with the news media. One was Roy Wilkins, who at the time was executive director of the NAACP. Wilkins got his start as the editor of black newspapers. Also, vice chair John Lindsay, mayor of New York City, recognized the power of television news, and he later became a regular guest host on ABC’s Good Morning America. The commission also hired several people with media experience, most notably Alvin Spivak, a former UPI White House reporter, who was an influential member of the commission staff. Larry Still, a reporter for black newspapers, was also on the staff.

Chapter 16: You end up with a mixed review of the commission, but you agree with many of its critics that its coverage of the media stood out. What sets that chapter in the report apart?

Hrach: The commission did a lot of smart things when it came to the news-media research. The commission hired Harvard professor Abram Chayes to do the news-media research. That helped because it was not politicians investigating the news media but rather a well-respected academic. Chayes recognized that previous attempts at news-media criticism fell on deaf ears. He decided instead of public hearings that he would have an off-the-record retreat and invite the top people in television and newspapers to discuss the issue. Then he also employed some relatively new social-science research, which added some credibility to the criticism.

Chapter 16: You argue that the Kerner Commission played a key role in revolutionizing the American newsroom. Why do you think it had the effect it did?

Hrach: The issue of rioting in American cities peaked in late July 1967 with the riot in Detroit. And while there were riots after that, they were not as severe. I would contend that one reason the rioting issue was tamed was that the news media started doing a better job reporting on race, poverty and the plight of African-Americans in major cities. That coincided with the release of the Kerner Commission report on March 1, 1968. The report put into black and white many of the things the news-media members were already concerned about, so it became a catalyst to make changes. Those changes included paying more attention to the black community, hiring African Americans, and also recognizing the media’s role in helping solve the nation’s problems.

Nashville native Clay Risen is the author of A Nation on Fire: America in the Wake of the King Assassination and American Whiskey, Bourbon and Rye: A Guide to the Nation’s Favorite Spirit. His new book, The Bill of the Century: The Epic Battle for the Civil Rights Act, appeared in spring 2014. He lives in New York, where he is an editor at The New York Times.

.jpg)