Black Futures Forever

Two books of Afrofuturist fiction envision Black possibility and protest

FROM THE CHAPTER 16 ARCHIVE: This review originally appeared on March 27, 2023.

***

Despite projections from think tanks like Prosperity Now and the Institute for Policy Studies, Black futures are on the rise. The past decade of Afrofuturist science fiction has offered us a view of Black possibilities in a world outside of the white gaze. Bestsellers like Tomi Adeyemi’s Children of Blood and Bone and blockbuster films like Ryan Coogler’s Black Panther attest to this new era of creative agency. Prose adaptations featuring the Marvel Comics hero, including Black Panther: Tales of Wakanda and Black Panther: Who is the Black Panther?, are no less exemplary of the genre’s recent dominance.

Continuing this series is the novel Black Panther: Panther’s Rage by Memphis author Sheree Renée Thomas. Thomas is no newcomer to the field of Afro sci fi, as she edited the acclaimed Black speculative fiction anthologies Dark Matter: A Century of Speculative Fiction from the African Diaspora (2000) and Dark Matter: Reading the Bones (2004). She is associate editor of Obsidian: Literature & the Arts in the African Diaspora and editor of The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction.

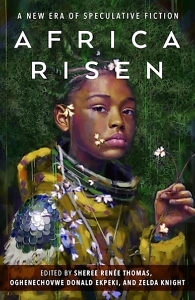

But Thomas’ contributions to the field do not stop there. She recently coedited another anthology of fantasy and science fiction from Africa and the African diaspora, Africa Risen: A New Era of Speculative Fiction. Her fellow editors are Oghenechovwe Donald Ekpeki (editor of The Year’s Best African Speculative Fiction, 2021) and Zelda Knight, a USA Today bestselling author. The anthology brings together 33 original stories that collectively redefine the boundaries of African and Afrodiasporic science fiction. Some stories are rendered in chapter-length form. Others begin and end in a few pages, like “Simbi” by Sandra Jackson-Opoku. With the dexterity of a master artisan, Jackson-Opoku weaves past and present together, taking the reader from slave ship to suburb in the space of a single paragraph.

In congruence with the breadth of the African diaspora, the language throughout the anthology varies in origin, style, and technicality. Many stories employ African or Caribbean words and phrases. For instance, in the story “Cloud Mine” by Tim Odueso, about villagers and the ethics surrounding their technologies for rain, Odueso invites the reader to a type of cultural education by dropping in words like “dadduma,” which he describes a few lines later as a prayer mat.

The stories that make use of more technical language, like Dilman Dila’s “The Blue House,” exemplify another type of Black possibility — a digital one. Dila’s protagonist is a femme African android named Cana-B70. She lives in a post-apocalyptic world, the result of an event called The Great Burn. In struggling to remember her former human face, Cana-B70 wrestles with her personal software: “Mem.sys. closed Organic.sys, but CPU-3 overclocked, and shut down, plunging her into blackness.”

The stories that make use of more technical language, like Dilman Dila’s “The Blue House,” exemplify another type of Black possibility — a digital one. Dila’s protagonist is a femme African android named Cana-B70. She lives in a post-apocalyptic world, the result of an event called The Great Burn. In struggling to remember her former human face, Cana-B70 wrestles with her personal software: “Mem.sys. closed Organic.sys, but CPU-3 overclocked, and shut down, plunging her into blackness.”

Dilman Dila examines the Black struggle to survive in a post-apocalyptic quasi-digital landscape, but she also brings class into the conversation. After The Great Burn, we discover that only those who could afford to become androids survived. Protagonist Cana-B70 and her family acquired money through serendipitous circumstances, and thus lived. Dila also invites us to explore new language to describe these reincarnated Black bodies. The protagonist’s search for spare parts to heal herself evokes Black women’s struggle with the healthcare system. How do we describe a failing body when we learn that it is not biological inferiority, but conflict at the intersection of class and race that cause bodies to break down? Ultimately, though, “The Blue House” is about the inseparability of the past, present, and future.

This interplay is also one of the major themes in Thomas’ Black Panther: Panther’s Rage. The novel chronicles the return of T’Challa, the Wakandan King, to his home. When he arrives, he finds the nation in unrest and divided by an unfamiliar nemesis, Killmonger. It is T’Challa’s prerogative, then, to contend with both his enemy and his own rage. The book features several subplots, the most notable of which is the romantic relationship between T’Challa and the Harlem-born singer, Monica Lynne. The mythos of the Black Panther surrounds a heart-shaped herb with matchless healing qualities. But the readers are left to wonder if Monica Lynne is T’Challa’s human heart-shaped herb: “‘East of the sun and west of the moon…’ the woman with the heart-shaped face and deep brown eyes sang, her hair a sparkling dark crown atop her head.”

The language utilized throughout the book will be familiar to those veterans of the Black Panther Universe. It is not localized to a particular region or nation in Africa. Rather, the Wakandan way of speaking employs an African lingua franca that consists of words from various parts of the continent. For instance, the Zulu word ukatana, which means kitten, is used both endearingly and ironically. Zulu is mostly spoken in the Southern region. Yet, the Golden City of Wakanda, the seat of the empire’s government, is also known as Birnin Zana. Birnin is the Hausa word for “city,” and Hausa is spoken in West Africa. Overall, the reader is treated to a pan-African aesthetic and linguistic experience. Black Panther in prose is no less regaling than the comics or films.

The language utilized throughout the book will be familiar to those veterans of the Black Panther Universe. It is not localized to a particular region or nation in Africa. Rather, the Wakandan way of speaking employs an African lingua franca that consists of words from various parts of the continent. For instance, the Zulu word ukatana, which means kitten, is used both endearingly and ironically. Zulu is mostly spoken in the Southern region. Yet, the Golden City of Wakanda, the seat of the empire’s government, is also known as Birnin Zana. Birnin is the Hausa word for “city,” and Hausa is spoken in West Africa. Overall, the reader is treated to a pan-African aesthetic and linguistic experience. Black Panther in prose is no less regaling than the comics or films.

A major issue that appears in both Africa Risen and Black Panther: Panther’s Rage is Afrodiasporic conflict. That is, issues of belonging. Yes, members of the diaspora are all Black, but who is truly African? In Black Panther, Monica is treated like an outsider in Wakanda. To the natives, she is just another American seeking to take from their country. She must prove her commitment to the country before she finds acceptance. In Africa Risen, “The Sugar Mill” by Tobias S. Buckell tells the story of a Caribbean islander whose African enslaved ancestors haunt him. He must choose between honoring their horrific deaths and the profitable sale of their land.

In this new and rebellious epoch of Afrofuturist literature, Black creatives are writing time for themselves and for their people. And in these literary renderings, like so many other mainstream works, Black futures consist of wars, discovery, heartache, family. So, what makes these books important? They declare Black people alive and full of agency in the future — which is its own type of necessary protest.

***

Africa Risen: A New Era of Speculative Fiction

Edited by Sheree Renée Thomas, Oghenechovwe Donald Ekpeki, and Zelda Knight

Tordotcom

528 pages

$27.99Black Panther: Panther’s Rage

By Sheree Renée Thomas

Titan Books

336 pages

$25.95

Kashif Andrew Graham is a writer and theological librarian, who was recently awarded the Humanities Tennessee Fellowship in Criticism. He enjoys writing poetry on his collection of vintage typewriters and is currently at work on a novel about an interracial gay couple living in East Tennessee.