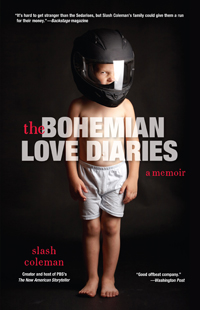

Bohemian Rhapsody

Slash Coleman’s new memoir is a funny, funky remembrance of family, art, and love

Slash Coleman, an award-winning performer and storyteller, is best known for his one-man Off-Broadway show and PBS special, The Neon Man and Me. In his new memoir, The Bohemian Love Diaries, Coleman shares his story of growing up in the South in the 1970s and 80s, surrounded by a family of off-beat artists whom the young writer finds alternately inspiring and confounding. It’s a funny tale, and heartfelt, about a family life that’s just as chaotic and creative as anything that comes out of an artist’s studio.

For Slash, growing up Coleman meant being called “Sanford and Son” by bullies at school who laughed at the lawn his father, a sculptor, littered with wacky shapes and forms. It also meant the complicated business of growing up Jewish in the South, and the story of Coleman’s Bar Mitzvah and his “Slash” moniker is one of the book’s funniest and most moving. The Bohemian Love Diaries recounts Coleman’s hapless, hopeful questing after both true love and a true artistic voice, ultimately telling a personal tale about what it means to become both an artist and a man.

For Slash, growing up Coleman meant being called “Sanford and Son” by bullies at school who laughed at the lawn his father, a sculptor, littered with wacky shapes and forms. It also meant the complicated business of growing up Jewish in the South, and the story of Coleman’s Bar Mitzvah and his “Slash” moniker is one of the book’s funniest and most moving. The Bohemian Love Diaries recounts Coleman’s hapless, hopeful questing after both true love and a true artistic voice, ultimately telling a personal tale about what it means to become both an artist and a man.

Coleman answered questions from Chapter 16 by email.

Chapter 16: You’ve written for television and for live storytelling performances. How is writing a book different?

Slash Coleman: I’d been making my living performing most of my childhood stories on stage for many years before I decided to put them in The Bohemian Love Diaries. Many were created using oral-tradition techniques and were never written down. I assumed that the transition would be an easy one: write what I spoke. Yet when I transcribed my oral stories onto the page, they didn’t work. My publisher was like “What the heck is going on here?” He assured me that the stories weren’t working on the printed page. At the time, I didn’t understand how different my oral stories were from my written stories. “These stories are so funny on stage,” I explained.

I’ve since come to understand that a lot of my humor on stage comes from my vocal quality, pauses, and the rhythm, cadence, and speed that follows specific dramatic plot points. These can only be replicated on the page with literary craft elements, which makes writing for live storytelling and television more like a combination of math and sculpting than writing.

Chapter 16: Your father, an artist, taught you that if you could draw a square and a circle you could draw anything. Have you discovered similarly elemental rules for writing?

Coleman: I’ve found that each story, when I hang out with it long enough, will tell me where it wants to go. It’s sort of like a gentle courtship of a lover who needs to feel safe before she’ll open up to you. I can’t go in for the kiss if I haven’t been properly introduced, and I can’t start holding hands ten minutes after I’ve met someone. Writing and the Venusian arts are a lot alike in that respect.

Chapter 16: In your author’s note you mention the challenge of balancing honesty, memory, privacy, and creativity in memoir writing. In The Bohemian Love Diaries, where was that balancing act the most difficult?

Chapter 16: In your author’s note you mention the challenge of balancing honesty, memory, privacy, and creativity in memoir writing. In The Bohemian Love Diaries, where was that balancing act the most difficult?

Coleman: For the majority of my writing life, I’ve been a fiction writer—using my writing to escape the world. No matter how bad my life was, I could always buy a blank notebook and a pen and escape into a world I created. My success as a writer didn’t come until I began to embrace memoir and the telling of true, personal stories. Rather than escape, I began to use my writing to confront my life and to examine it more closely.

As I wrote those scenes when I was older in The Bohemian Love Diaries, I kept wanting to embellish and escape, yet I found the closer I stuck to the truth, the more interesting and the weirder the scenes actually were. I mean, in the opening scene my dad is wearing a pair of bleach-spotted jeans and a Nazi soldier helmet with fake pigtails, and I’m standing in a shopping cart at midnight. There’s no embellishment there. Yet that scene happened when I was eight years old. There’s a certain distance and safety with events that happened so long ago that naturally lend themselves to the literary world. With more recent events, I found it challenging to maintain the distance and perspective necessary to make the scene work in a way that stayed consistent with my style (which is writing memoir that reads like fiction).

Chapter 16: In the book, you mention an old television commercial for an Evel Knievel stunt, noting that the tagline—“Don’t miss the Bicentennial Event of the Bicentennial”—sounds like it was written by a kid for other kids. Did you have a specific audience in mind for The Bohemian Love Diaries?

Coleman: I feel my book was “written by a kid for other kids,” too—for those young and young at heart.

Chapter 16: Your development as a young writer was inspired by two rather different heroes: Richard Brautigan and Ernest Hemingway. What was it about each of these authors that spoke to you as a younger reader?

Coleman: Actually, I think these two writers are more similar than different. One emulated the other from his simple, clean writing style down to the way he chose to end his life. I fell in love with each, though, because their writing never got in the way of the story. Plus, most of their books are really, really short, and as a new reader (I didn’t start reading books until my junior year in college), I found thin books were less intimidating at the time.

Chapter 16: Love Diaries outlines three generations of creative Coleman artists. Where do you stand on the nature/nurture question on the origin of artistic ability?

Coleman: My two twin sisters work as dental assistants. They were exposed to the same creative world that I was growing up, yet they didn’t choose to become artists. My mom was raised by two artists and became a schoolteacher. Henry Miller said, “Artists receive transmissions from the sensitive side of the world from invisible antennae.” I think we all have these invisible antennae, period.

Shows like “American Idol” and viral Youtube videos which make ordinary people into overnight rock stars reveal a fundamental shift in not only how our culture views creativity but the ways we seek growth as human beings. Everyone is an artist. It’s my hope that part of personal mission in my writing reveals that.

Slash Coleman will discuss The Bohemian Love Diaries at the twenty-fifth annual Southern Festival of Books, held in Nashville October 11-13, 2013. All festival events are free and open to the public.