Bringing up the Dead

Lorrie Moore discusses death, humor, and her sensational new novel

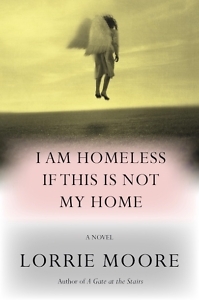

Lorrie Moore’s fourth novel, I Am Homeless if This Is Not My Home, begins six years after the Civil War’s end. Libby, a Union sympathizer and spinster who runs a boardinghouse in the South, writes letters to her sister about a boarder who has quite a bit in common with John Wilkes Booth. Libby is “personally unreconciled to just about everything” — with a crackerjack sense of humor about herself, the nation, her boarders, and death.

Ten pages in, Moore introduces the second narrative. It’s 2016, and Finn is a history teacher on administrative leave. He has traveled from middle America to New York to visit his brother, who is dying in hospice. Despite the circumstances, the tone remains jaunty. Then, Finn receives news about his long-suffering, suicidal ex-girlfriend Lily, and it’s like Moore has torn a hole through the book and pulled you into its moist, dark lair where the presence of death is close enough to taste.

Finn and Libby’s two stories don’t mirror one another, nor do they neatly explain the mysteries within the characters’ hearts. Rather, they refract the same light, bouncing it into corners and revealing the unearthly and sometimes freakish spaces where we meet our grief. You may try to resist the ride — Moore admits it can be a difficult book to read — but the characters are so charming, their complexes so relatable, that your only option is to get in Finn’s Subaru and surrender to Moore’s signature dry sense of humor, mastery of metaphor, and singular voice.

She talked with Chapter 16 about I Am Homeless if This Is Not My Home. The conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Chapter 16: I love your book. It was such a pleasure to read and sometimes so hard to read. But I just felt so propelled by these two voices that I couldn’t put it down.

Lorrie Moore: It’s not for everybody, so when it turns out to be for somebody, I just think, “Oh, good!” Some people are quite baffled by it. I thought men would get it, but it’s getting more flummoxed responses from men than from women.

Chapter 16: What kind of research did you do for this book?

Moore: I looked up boardinghouses in the 19th century. [I did] research on the [John Wilkes] Booth family. I’m an expert on the Booth family if there’s anything you want to know — his siblings, parents, his bigamous dad. … The boardinghouse story, written in letters and a diary form, comes out of the 2016 story. It’s a document within that story. [Both stories] have transporting the dead, and they both have the past coming alive again. They don’t fit perfectly. I think some people want … these two narrative parts to sort of click in and explain each other perfectly. They have overlap, and they have themes in common.

Chapter 16: I won’t spoil this for the reader, but their overlap felt both unexpected and inevitable at the same time. I glanced at a couple reviews and saw that some elements of the novel were described with spoilers. This always disappoints me!

Moore: I think it’s a very hard book to review. I review books sometimes, and I wouldn’t want to review this book, so I’m interested in how other people are reviewing it. Some people, as you say, give too much away. They give plot summary. Or they throw up their hands. Some people are really trying very hard. Others are not. But it’s a hard book to talk about.

Chapter 16: Do you usually read your reviews about your work?

Moore: I am this time, because they’re coming up early, and I’m going on the road soon. I don’t read every single review. If I start a review and I feel I know what it’s saying, [I stop reading]. I’m not one of these precious writers who feels that their ego can’t take it, or that they just don’t care about the reviews. I’m a reviewer myself. So I am interested in how reviewers do it as a craft. … I try not to obsess over them. And they’re all different. … After the book comes out and has been out for a while, the reviews all sound the same to you.

Moore: I am this time, because they’re coming up early, and I’m going on the road soon. I don’t read every single review. If I start a review and I feel I know what it’s saying, [I stop reading]. I’m not one of these precious writers who feels that their ego can’t take it, or that they just don’t care about the reviews. I’m a reviewer myself. So I am interested in how reviewers do it as a craft. … I try not to obsess over them. And they’re all different. … After the book comes out and has been out for a while, the reviews all sound the same to you.

Chapter 16: Did you learn anything about grief and dying from these characters?

Moore: I think when I was writing this, I wondered whether [Finn] would understand suicidality by the end or [if he would] still be angry at it, as a sort of brutal mystery that he couldn’t comprehend. And in the end, he’s not going to ever understand, because I think it actually is very hard to understand. [Lily] wants him to understand. She says, “Maybe you should read a book about it.” … She understands that he doesn’t get it. It’s an illness. It’s a very mysterious illness for those of us who don’t suffer from it. I did wonder whether he would somehow do a kind of mind merge and get it, but he doesn’t. Just like me. … I think it’s hard for people who don’t suffer from it to understand it.

Chapter 16: Finn and Lily’s long conversation is like an endless bit. They answer questions with questions. They free associate, they use metaphor and allegory way more than average people. And it’s kind of exhausting, but it’s still endearing. It’s a shared language of people who have known each other intimately for a long time. It reminded me more of siblings than of lovers.

Moore: But I do think in romantic relationships, one does become like siblings — that you’re just very close, living in the same house. And you share all that. … You’ve racked up a lot of time together. There’s also the phenomenon of the road trip. There’s a lot of idle talk on road trips — people just saying anything in the car. … A lot of it is stupid and silly, and some of it is revealing and some of it’s not, but it’s a combination of all those things that two people who know each other pretty well when trapped in a car might say.

Chapter 16: What role do you think humor can play in death and dying? While it’s a very sad book, I think it’s also a funny book.

Moore: I don’t really think of it as that funny. I think of it as sad. … Humor does different things in different places. Sometimes it’s not even meant to be funny. It’s just how people talk. And sometimes it’s meant to relieve tension. And sometimes it’s kind of meant to be a token of generosity toward the person — let’s have a little laugh. Humor can do all kinds of things. Typically, humor is buried tension that comes to the surface. But it can also be a whole bunch of things that can reveal some odd things that are on a character’s mind.

Chapter 16: I can’t escape the thought that you wrote this partially during the pandemic when it felt like death was looming all around.

Moore: Yeah, it’s not explicitly about the pandemic at all. And yet it has a sort of isolated feeling. All the characters feel a little isolated. And, of course, there’s illness and, of course, there’s death. And I did know people who died in the pandemic, and it was very sad. I’m getting older, so I know more and more people who are on the other side now. I did feel surrounded by death and I thought, “This book is going to be about that.”

Erica Ciccarone is a writer, journalist, and editor living in Nashville.