Brother Bill?

Daryl A. Carter reckons with the ambivalent racial legacy of President Bill Clinton

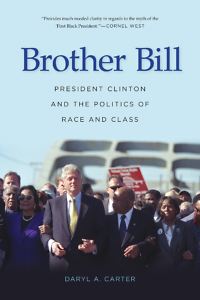

Daryl A. Carter’s Brother Bill: President Clinton and the Politics of Race and Class, is a thorough, timely, and essential history of the complicated racial and class politics of the so-called New Democratic movement of the 1990s. From judicial appointments to crime and welfare policy, Carter uncovers the complicated legacy of Bill Clinton, the man once popularly imagined by some as “the nation’s first black president.”

Carter, a Ph.D. graduate of the University of Memphis and an associate professor of history at East Tennessee State University in Johnson City, recently answered questions from Chapter 16 by email.

Carter, a Ph.D. graduate of the University of Memphis and an associate professor of history at East Tennessee State University in Johnson City, recently answered questions from Chapter 16 by email.

Chapter 16: What challenges come with writing the history of the very recent past?

Daryl A. Carter: Writing about the recent past is difficult because of the perils associated with memory. Most Americans older than twenty-five remember President Clinton. The partisanship, which defined much of the 1990s, tends to influence how we view those years. Democrats still view Clinton as a much persecuted political leader who brought back the economy, instituted smart domestic policies, and didn’t engage the nation in questionable foreign entanglements. Republicans view Clinton as amoral, undisciplined, and representative of much of what was wrong with the 1960s—civil rights, women’s rights, anti-Vietnam protestations, and sexual freedom.

It is very important to think critically about the events under examination. I had to force myself to ask hard questions about how and why Clinton was pursuing certain things. For example, in order to understand Clinton’s politics, I had to seriously consider the importance of the Democratic Leadership Council and its philosophical framework. The New Democrats were a real entity dedicated to pursuing moderate, centrist policies that embraced pro-growth economic policies and were equally suspicious of too much government intervention. In order to do this, I had to concentrate on both what Clinton was doing and the past that informed his politics.

Chapter 16: Because of our current presidential contest, your book is timely in any number of ways. I’m thinking here in particular about recent criticisms of Hillary Clinton over Bill Clinton’s signing of the 1994 Crime Bill. More than a few commentators, including you, see that legislation as a major contributing factor in the mass incarceration of African-American men in this country. What do you think has been missing in the public debate about that legislation?

Carter: I think the racism, both overt and covert, that informed the thinking which resulted in the 1994 Crime Bill has not been considered appropriately. We tend to view crime as race-neutral, but race, especially since the 1960s, has always been a part of the equation. On the surface, harsh punishment for criminal behavior makes sense. If you commit a crime, you do the time. Who gets targeted for arrest, prosecution, and incarceration, however, is something entirely different. The criminal-justice system has myriad ways to impact Americans. Some are given a slap on the wrist. Others are given harsh sentences.

The media played a major role in how we viewed crime. For instance, during the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s, the media frequently displayed African Americans in a negative light. It drove ratings. It increased viewership. And it scared the hell out of white middle-class Americans. As crack cocaine took over inner-city communities, the violence and dysfunction that accompanied it became irresistible to executive producers and print reporters. This played into notions of blacks as irresponsible, shiftless, and dangerous. These notions go all the way back to the Reconstruction era, when stereotypes about former slaves told hold and undermined the hope of the Civil War.

Chapter 16: You show in the book how Bill Clinton’s careful positioning of himself as a centrist, “new Democrat” and leader of the Democratic Leadership Council (DLC) put him at odds at times with the Congressional Black Caucus (CBC). You suggest on a few occasions that Clinton and the DLC were actually closer to popular attitudes—black and white—on some issues (say, welfare reform) than was the CBC. What do you think best accounts for this difference?

Chapter 16: You show in the book how Bill Clinton’s careful positioning of himself as a centrist, “new Democrat” and leader of the Democratic Leadership Council (DLC) put him at odds at times with the Congressional Black Caucus (CBC). You suggest on a few occasions that Clinton and the DLC were actually closer to popular attitudes—black and white—on some issues (say, welfare reform) than was the CBC. What do you think best accounts for this difference?

Carter: Most of the Congressional Black Caucus often came from urban communities. Those communities had different needs and complex problems, which usually weren’t present in white communities. It is also important to understand that many of those members had been active in the civil-rights movement. Consequently they were understandably sensitive about public policies that could undermine the progress achieved since the 1950s. Those communities often had issues with crime and poverty and lack of opportunity. So they needed government support and intervention but were resentful of the ways in which government had interacted with them in the past. The resentment came from police brutality, racial profiling, poor schools, poor service, invasions of privacy, and a number of other slights, abuses, and indignities.

At the same time the schools needed quality teachers to instruct the youth. The cities needed smart, sensitive. and effective law enforcement and government enticements to bring businesses and corporations that could offer decent paying jobs. So when Clinton pushed the crime bill in 1993-94, members of the CBC were greatly concerned about the impact on their constituents. When Clinton pushed welfare reform it appeared to CBC members that Clinton was indulging the racial narrative that African Americans disproportionately used the government program, that African Americans lack a strong work ethic.

While the CBC did not like these policies and often saw them as punitive. other African Americans saw the legislation as an improvement over the status quo. Millions of African Americans scratched and clawed their way into the middle class and resented the crime and poverty that for them was too close for comfort.

Chapter 16: The legacy of the civil-rights movement counts as one of the more interesting sub-themes in the book. It’s safe to say that your interpretation is rather different from popular or triumphal narratives of the movement. Desegregation had its ironic outcomes. What is the greatest disconnect between popular understandings of the movement and its ultimate effects on African Americans in this country and why?

Carter: The greatest disconnect in my opinion is the class issue. Ironically, many of those who participated in the civil-rights movement did not enjoy the gains of the movement. While it is true that black Southerners gained the right to vote and de jure segregation came down, it did not mean those people ended up in a better socioeconomic position than they were before the movement.

Also, I think a mythology has developed that is not healthy. The civil-rights movement was dangerous. It was fractured by division between North and South, poor versus more affluent people, urban against rural people. Today we look at that era and see peaceful marches for freedom. Yet in the South one could lose one’s life, and many did lose their lives. While no one would want to go back to the way it was, there was a certain stability. On a class basis most Americans lived together in the same neighborhoods. Civil rights changed this by allowing for middle- and upper-class African Americans to move into white residential areas, which left poor and working-class African Americans behind and sometimes devastated those old communities. So I think there is a lack of unity within the African-American community.

Chapter 16: Bill Clinton’s background in the white, working-class South has sometimes been cited as a contributing factor in his mostly warm relationship with African-American Southerners. Yet one could argue that, in the history of the South at least since the collapse of the Populist movement in the 1890s, white elites have often pitted poor whites against African Americans. The race-baiting of poor whites by white Southern leaders has been a mainstay of Southern politics for over a century. Why do you think Bill Clinton appeared to escape that influence? Did he?

Carter: I do not believe Clinton escaped it at all. I think he adapted to new political and cultural realities. Clinton is not a racist. He is also responsible for helping numerous African Americans personally. Equally important, he stood steadfast in support of affirmative action, which helped many African Americans gain educational and professional advancement. But that does not mean Clinton is not a part of said tradition. This was clearly on display as the former president went after then-Senator Barack Obama in 2008 in racially charged ways.

Clinton benefited from having family members who were not dedicated racists. Coming from a family near the bottom of the ladder and, at times, scandalous, Clinton could relate to blacks in Arkansas in ways that other politicians could not. This was the beginning. Next, Clinton left at eighteen to attend Georgetown University in Washington, D.C. It provided Clinton with experiences and exposure he would never have had in Fayetteville or Little Rock. By the time Clinton returned to Arkansas to teach at the law school at the University of Arkansas he was in his mid-twenties. He had travelled around the world. He had campaigned for the Democrats in 1968 and 1972. I really think he was appalled by the treatment of African Americans in the South yet smart enough to understand that old ways of doing politics were coming to an end. In addition, by the time Clinton returned to Arkansas the Voting Rights Act of 1965 was transforming politics as millions of African Americans throughout the country were gaining the franchise. Arkansas was not immune to this fact of life.

Chapter 16: Bill Clinton’s status as a centrist “New Democrat” seemed to augur a more complex electoral map in the South. In other words, a popular narrative has surfaced recently that the solid Democratic South was simply replaced over time by a solid Republican South. Yet, Bill Clinton managed to win a few Southern states in 1992 and 1996. Barack Obama had less success but did win North Carolina in 2008. A large part of this had to do with strong showings from minority voters in those states. Does this tell us anything? Is Bill Clinton sui generis, or do you think a politician in the mold of a Bill Clinton could still experience success in the South? If not, what has changed in your opinion?

Carter: I think it is a very different world from the one Clinton was campaigning in in 1992. We are in the era of terrorism. The Great Recession wiped out millions of Americans. Immigration and diversity are much greater than they were nearly twenty-five years ago. Much of the blowback today comes from the realization among many that the United States will be a minority-majority country within the next three decades. It is not just anger that the civil-rights movement actually happened, as it was in Clinton’s time, but that white Americans are losing their grip on the nation. Nothing demonstrated this more than the election of Barack Obama. It is why Trump is so popular among many white Americans, especially those on the lower end of the socioeconomic spectrum. In short, I do not believe Clinton could win in the South today. Even in Arkansas he would probably lose.

Peter Kuryla is an associate professor of history at Belmont University in Nashville, where he teaches a variety of courses having to do with American culture and writes scholarly articles about American political thought and the civil-rights movement.