Buckled Up for a Wild Ride

With the publication of Full Body Burden, Kristen Iversen’s life changed

Full Body Burden is a book I wasn’t sure would ever get published. It’s personal. It’s controversial. Sometimes funny, often dark, it tells a hidden, secret side of American history and how that history affected the lives of individual people—that is, me—as well as my parents, my siblings, and our horses and dogs and cats. Not to mention our neighbors and everyone else living in the area. Few people knew the story and devastating legacy of the secret Rocky Flats Nuclear Weapons Plant, just down the road from my family’s home near Denver.

Now they know.

There’s a big difference between writing a book, your head buried in research and line edits, and going out into the world and talking about it. I’m an introvert and a slow convert to social media. A little bit like Emily Dickinson, I tuck most of my writing into my desk drawer.

Those things are no longer true.

When Full Body Burden sold at auction to Crown, and then sold again in the U.K., my life changed. Suddenly the world wanted to hear my story.

Just before the book hit the shelves, I had my first interview, an hour-long spot on the international radio show If You Love This Planet with Helen Caldicott, one of my heroes. I was so nervous my voice trembled. The interview ended, and she asked me to stay on the line. Damn, I thought. I blew it.

Just before the book hit the shelves, I had my first interview, an hour-long spot on the international radio show If You Love This Planet with Helen Caldicott, one of my heroes. I was so nervous my voice trembled. The interview ended, and she asked me to stay on the line. Damn, I thought. I blew it.

“I have some advice for you,” she said. Her tone was almost maternal.

“Yes?” I asked.

“Buckle your seatbelt and take your vitamins,” she said. “Your life is about to change.”

In the following months, I crisscrossed the country so many times I couldn’t keep track of time zones. The initial book tour snowballed into presentations and readings in more than twenty states, three countries, and too many cities to count. I spoke to environmental organizations, writers’ groups, schools and universities, museums and book clubs. I was invited to speak at places I had never dreamed of, places like the National Museum of American History at the Smithsonian and on the steps of the Capitol in Washington, D.C. I read at my favorite bookstores—Powells, Malaprop’s, Collected Works—and the Tattered Cover in Denver, where years ago, when I was in graduate school, the owner had been kind enough to let me carry a monthly credit for my books. Barnes & Noble believed in Full Body Burden right from the start (and chose it as a finalist for the Discover Award).

I learned to live out of a suitcase—truly live out of a suitcase. I started out with two big bags and lots of stuff. The suitcases wore out, and so did my back. Now I travel with a single carry-on with two sets of no-iron clothes and lots of scarves and necklaces. I take two pairs of shoes, not six—one on my feet and one in my bag. When I pack for a new trip, I just borrow a trick from a writer friend: pack a bag, take half out, and then take half out again.

I gave up packing my purse with three or four novels (a long-time habit, regardless of the length of the trip) and learned to love my e-reader.

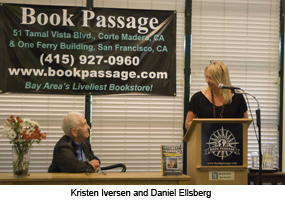

I discovered I could write on planes, in hotel rooms, and—if necessary—in a cab. Big planes, small planes, puddle jumpers, jets—sometimes they land on time, sometimes they don’t. Daniel Ellsberg, another long-time hero of mine who for decades has challenged government and corporate secrecy regarding Rocky Flats, was scheduled to introduce me at my reading at Book Passage, near San Francisco. My schedule was very tight. The plane was delayed for two hours. I changed clothes in the women’s room at the airport and tried not to be nervous. Finally we landed, and I jumped into a cab. Immediately we hit gridlock traffic. The driver—a terrific guy who never displayed a hint of anxiety—took back roads and side streets and a winding drive through the Presidio. “Don’t worry,” he said. We arrived with two minutes to spare. After the reading came the best part of the day—a two-hour lunch with Ellsberg and his delightful agent, Andy Ross. We talked about Rocky Flats and politics and writing.

I learned a writer doesn’t really know what her book is about until she can describe her book to someone else—again and again and again. And then she finally begins to understand her own work.

I learned a writer doesn’t really know what her book is about until she can describe her book to someone else—again and again and again. And then she finally begins to understand her own work.

To my great surprise, I’m no longer nervous in front of a camera. I’ve found that I like doing interviews, and in fact I’m a little bit of a ham, at least on the radio. I was fortunate to be on NPR’s Fresh Air, Helen Caldicott’s If You Love This Planet, and other shows like Coast to Coast. But the most fun I had was at a tiny, all-volunteer radio station in Idaho Springs, Colorado, in a studio the size of a mountain hut, filled with spider plants, old album covers, and Grateful Dead posters. The host played 70s hard rock during the breaks. He hugged me when I left. “I dig your book, man,” he said.

It’s been a breathless, intense time. But there are three ways in which my life—and the way I think about writing—has significantly changed.

I fell in love with readers. Writing is a lonely business. During the ten years of writing and research that it took to finish Full Body Burden, I never really had a sense of audience or market. I just knew it was a story I had to tell before I could write anything else.

I discovered how remarkable it is to walk into a room of thirty people, or stand in front of a crowd of 3,000, and know that everyone there has read my memoir. “How’s your sister?” someone might ask. “What happened to your horse Tonka?” Audiences always had great questions. We talked about everything from plutonium contamination to nuclear policy, 70s music to bell-bottom jeans.

Usually I stayed in hotels, but sometimes I was invited to stay in people’s homes, and I was grateful to share briefly in their lives. In Dallas I stayed with a woman whose husband had been a key member of the Johnson administration, and we spent an evening drinking wine and going through her scrapbook of photos with Johnson and JFK. In Vermont I stayed with a family deeply committed to environmental causes, in a house tucked away in the woods and filled with books and dogs and passionate conversation.

From my home I Skyped with classrooms and book clubs around the country. I feel almost as if I’ve gotten to know each reader personally. The connection between a writer and a reader is intimate.

I have new faith in the power of storytelling. In the short time since Full Body Burden was published, much has changed. There’s greater awareness at the local and national level about Rocky Flats and the way our nuclear legacy, and current nuclear policies, affect us both now and in the future. I received countless emails and letters from people who live around Rocky Flats and other nuclear sites like Hanford, Los Alamos, Oak Ridge, and the Savannah River site. People came out of the woodwork to share their stories. A Colorado resident started a petition opposing development near the contaminated Rocky Flats National Wildlife Refuge (a site slated to open for public recreation), and the petition garnered thousands of signatures. Citizens are calling for more information, more testing, and truth and transparency from government and corporate officials.

Books can make a difference in the world. My story led to the telling of many stories. These stories are leading to positive change, for all of us and for the environment.

I rediscovered my family. I wasn’t sure how my father, my sisters, and my brother would react when my book was published. (My mother, who had been very supportive, passed away before the publication date.) Would they like it? Would they hate it? They had read sections of it, but I knew it would be different when the book actually hit the shelves. Every writer who writes about personal experience worries about how the people they love will respond to the book.

I rediscovered my family. I wasn’t sure how my father, my sisters, and my brother would react when my book was published. (My mother, who had been very supportive, passed away before the publication date.) Would they like it? Would they hate it? They had read sections of it, but I knew it would be different when the book actually hit the shelves. Every writer who writes about personal experience worries about how the people they love will respond to the book.

To my surprise, the book brought my family closer together. The process wasn’t easy, but we were able to talk about things we’d never talked about in the past. Our family dynamic changed, and I grew close to my father after years of distance and non-communication. Even now, my sisters and brother, who also travel frequently with their jobs, show up at my readings when they can.

I guess you could say I’m no longer, technically, an introvert. Emily Dickinson, be gone! It changed so fast I scarcely noticed. I’ve come full circle on social media—it’s a great way to connect with readers and other writers, and I enjoy it. But I can’t indulge too long. Whether I’m at home or on the road, I know that, as always, I have to carve out a few hours each morning to write. I turn off my phone, shut down my email, get off the Internet, and get down to business. I often think of the words of George Orwell: “Writing a book is a horrible, exhausting struggle, like a long bout of some painful illness. One would never undertake such a thing if one were not driven on by some demon whom one can neither resist nor understand.” Knowing that there are empathetic readers beyond the walls of my office makes it easier to live with that demon.

I keep thinking my life will slow down. It hasn’t. But I’ve got my eye on the seatbelt sign, and I’m taking my vitamins.

Copyright (c) 2013 by Kristen Iversen. Director of the M.F.A. program in creative writing at the University of Memphis, Iversen is the author of Full Body Burden: Growing Up in the Nuclear Shadow of Rocky Flats, which has just been released in paperback.