Building Stories

Robin Hood and James A. Crutchfield take readers on an architectural tour of Tennessee history

It’s no mistake that the word history holds the word “story” within it. A new kind of history recorded by a pair of accomplished Middle Tennesseans— Pulitzer Prize-winning photographer Robin Hood and James A. Crutchfield, author of fifty books—isn’t a dreary textbook full of forgettable facts and it doesn’t feature the ponderous tones of an overbearing expert guiding you through predictable, well-worn paths of the Volunteer State’s bygone days.

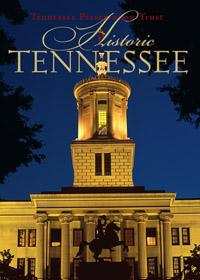

Historic Tennessee: Photographs by Robin Hood takes readers on a tour through the limestone, brick, and lumber of Tennessee’s most compelling historical sites and buildings. Full of freewheeling anecdotes, hair-raising adventures, and unforgettable characters, this history book reads like a novel and, thanks to Hood’s striking images, is much more an artsy coffee-table volume than a stuffy history tome. It also offers a look at the important work that’s being done to keep these landmarks, and their history, intact for generations to come.

Historic Tennessee: Photographs by Robin Hood takes readers on a tour through the limestone, brick, and lumber of Tennessee’s most compelling historical sites and buildings. Full of freewheeling anecdotes, hair-raising adventures, and unforgettable characters, this history book reads like a novel and, thanks to Hood’s striking images, is much more an artsy coffee-table volume than a stuffy history tome. It also offers a look at the important work that’s being done to keep these landmarks, and their history, intact for generations to come.

Chapter 16: How did you decide to publish a book about Tennessee’s architectural history?

Hood: After doing two other books about Tennessee’s traditions and people and scenery, I felt like there were [already] many, many really good books done on Tennessee’s history and Tennessee’s heroes, but there had never been a comprehensive book that illustrated all the important sites across the state in one volume. I wanted to take them together as a tapestry and tell the story of Tennessee—its exploration, its settlement, its growing government expansion, from Upper-East Tennessee in a westward expansion all the way to the banks of the Mississippi.

So that’s what Jim and I chose to do: to present these different sites across the state in an east-to-west fashion, beginning with Sycamore Shoals, which was one of the first—if not the first—settlements in East Tennessee, long before we were a state, and was the site of the first democratic form of government in America. You had a group of settlers living out on the frontier who said, “We’re going to have our own democratic form of government and control the way we live.” That was historic! Long before the Constitution [was written], that was here in Tennessee.

So that’s what Jim and I chose to do: to present these different sites across the state in an east-to-west fashion, beginning with Sycamore Shoals, which was one of the first—if not the first—settlements in East Tennessee, long before we were a state, and was the site of the first democratic form of government in America. You had a group of settlers living out on the frontier who said, “We’re going to have our own democratic form of government and control the way we live.” That was historic! Long before the Constitution [was written], that was here in Tennessee.

Chapter 16: How did you get involved with the project?

Crutchfield: Robin and I had worked on several projects before, and he approached me on this one, which was right down my alley. I was very enthusiastic about it and just jumped right in. The types of history that are covered in this book are the ones that I have written about my entire career: biographical sketches, histories of buildings, architectural history.

Chapter 16: In the book you remark on the astonishing pace of architectural preservation in our state.

Hood: I see it more and more. The preservation of buildings goes hand-in-hand with public consciousness of just about everything. We’re building green buildings now. We’re recycling materials that we used to throw away. People are more conscious about the value of the re-use of things, whether it’s a plastic bottle or a remarkable building.

This whole idea of raising the consciousness of the public about preservation of buildings goes right to the heart of the mission of Tennessee Preservation Trust and their desire to get involved with this book project. The books we publish serve two purposes: they raise money for an organization like Tennessee Preservation Trust to continue their mission, but they also raise a clarion call for the public that might not otherwise be engaged in this story. If we did a book that was just a technical book about preservation we’re preaching to the choir, because the people who are going to read that book are already involved in preservation. What we want to do is reach Tennesseans across the state, both students and adults, about the treasures we have here that we take for granted.

This is certainly not a knock against public education by any means, but when I studied history in school, you memorized dates and names and places and treaties, but the anecdotal stories behind these buildings, these houses and these forts, is lost a lot of times [on] school children and adults. I can tell you that people pass the State Capitol every day and they know that that’s our State Capitol, and it’s been there for a long time, and that it’s a pretty significant building. But I bet far less than fifty percent of those people know that it’s the second-oldest state capitol still in use in the United States, that the architect is buried in its walls, that it was a federal fort during the Civil War, that a U.S. President is buried on its grounds, that the women’s right to vote—in the whole United States—was passed by one vote right there in the halls of the State Capitol. When you bring those stories out, then it ceases to be just a marble building on a hill in the center of our government. It’s an incredible repository of great stories about our past.

This is certainly not a knock against public education by any means, but when I studied history in school, you memorized dates and names and places and treaties, but the anecdotal stories behind these buildings, these houses and these forts, is lost a lot of times [on] school children and adults. I can tell you that people pass the State Capitol every day and they know that that’s our State Capitol, and it’s been there for a long time, and that it’s a pretty significant building. But I bet far less than fifty percent of those people know that it’s the second-oldest state capitol still in use in the United States, that the architect is buried in its walls, that it was a federal fort during the Civil War, that a U.S. President is buried on its grounds, that the women’s right to vote—in the whole United States—was passed by one vote right there in the halls of the State Capitol. When you bring those stories out, then it ceases to be just a marble building on a hill in the center of our government. It’s an incredible repository of great stories about our past.

Chapter 16: How can writing bring history to life?

Crutchfield: Well, the watch-word today to drive these ideas home is to make the presentation of the material—whether it be text, photography, original art, or anything else—contemporary with the ideas and the ideals that readers have. I think that means a lot of color, a lot of anecdotal material, a steering away from the staid history that was written so we could memorize all of those dates and battles that nobody cares about anyway and forgets after they get out of school. The point is, try to make it engaging in all the aspects of presentation. Make it attractive.

Books now are becoming very hard to sell, I don’t care who the writer is. The Internet and the e-book make paper books harder and harder [to sell]. Publishers are having a hard time. Book distributors are having a hard time. Bookstores are having a hard time because the book is not what it was thirty, thirty-five years ago. We’ve got to come up with a way to keep the printed page out there, to make these things survive for centuries.

Books now are becoming very hard to sell, I don’t care who the writer is. The Internet and the e-book make paper books harder and harder [to sell]. Publishers are having a hard time. Book distributors are having a hard time. Bookstores are having a hard time because the book is not what it was thirty, thirty-five years ago. We’ve got to come up with a way to keep the printed page out there, to make these things survive for centuries.

Chapter 16: You call Tennessee’s historic buildings the state’s “first green buildings.” Could you elaborate on that idea?

Hood: Let me preface this by saying I’m not an architect and obviously I’m not knowledgeable about the things that go into green building. To be sure, a lot of the older buildings aren’t energy efficient and they have to be brought up to standards, but bringing an old building up to standards is far less expensive and far less intrusive on the use of materials than tearing it down and putting up a new one. If the people that wanted to tear down the old buildings and put up new ones had their way, we wouldn’t have a Ryman Auditorium in downtown Nashville. That came within a whisper of being torn down. Now it’s a very vibrant, money-making building. So that’s one example of re-use. You can’t replace limestone and brick and some of the materials they used with steel and plastic and glass and have the same aesthetics. There are some beautiful modern buildings being done, but the aesthetics of some of the classic buildings and classic materials will be appreciated forever, as long as they’re preserved.

Crutchfield: The entire Second Avenue district, which is now the entertainment district of Nashville, brings in how many tens of millions of dollars to Nashville and Middle Tennessee yearly. At one point this area was in jeopardy. When I was a child, the entire public square was surrounded by all those beautiful three- and four-story Victorian Mercantile warehouses and buildings. You can imagine what it would look like today, completely surrounded by those absolutely gorgeous buildings which were there when I was a kid. [During] the seventies, preservation groups in Nashville finally got their acts together. Historic Nashville was one of those very earliest ones. They finally got together with a number of architects and came up with mission statements to save some of that absolutely beautiful waterfront architecture.

Chapter 16: The book’s mission statement includes a funny observation: “Great architecture has only two natural enemies: water and stupid men.” What are the biggest challenges facing historic architecture in the state?

Crutchfield: I guess I am a little cynical on a subject such as this, but the largest danger is what the quote said: the stupidity of man. The second one I think is about the bottom line. It’s money. For some reason there is an attitude, whether it’s true or not, that it’s far easier to wreck fourteen square city blocks, take it down to the ground, dig a hole 100 feet into the ground, and come up with a sixty-story skyscraper, rather than restoring those five-, six-, seven-story buildings which together have just as much square footage as that skyscraper does.

Back in the sixties and seventies, everybody was standing around and laughing, “Why are we doing this? Why are we saving stuff when you can go to the store and buy another one for a quarter?” Well, you know, it’s taken forty years, fifty years, for that to catch on. You can’t pick a newspaper up without reading “green” this [or] “green” that. And the kids who are being born today will have been raised in this environment, and hopefully it’ll be that way from then on. The hard hump is getting over the existing generation—or generations—who grew up in that consciousness that it really doesn’t matter.

Back in the sixties and seventies, everybody was standing around and laughing, “Why are we doing this? Why are we saving stuff when you can go to the store and buy another one for a quarter?” Well, you know, it’s taken forty years, fifty years, for that to catch on. You can’t pick a newspaper up without reading “green” this [or] “green” that. And the kids who are being born today will have been raised in this environment, and hopefully it’ll be that way from then on. The hard hump is getting over the existing generation—or generations—who grew up in that consciousness that it really doesn’t matter.

Hood: It’s a little like a battle against insurgency in the Middle East: the battle will always be there. There will always be people that won’t have appreciation for a building that’s been around for 150 years. That battle’s not over, and that’s one of the purposes of this book and is certainly one of the purposes of the Tennessee Preservation Trust—which, by the way, is a partner and an affiliate of the National Historic Preservation Trust. All the proceeds from this book go back to Tennessee Preservation Trust and their mission. While that’s very nice, this book will be interesting to people who don’t know a whit about the history of preservation. It’s got some great anecdotal stories, whether it’s about one of our presidents and the way he settled in Middle Tennessee, [or] about a Civil War battle that was fought in Franklin and the thousands of soldiers that died in one particular building, or [about] a little house where a descendant of slaves grew up to be a Pulitzer Prize-winning writer. These buildings house incredible stories, and that’s what’s going to be fun for the reader: to open the front door of these buildings we present and see the story inside.

Chapter 16: What are some of your favorite stories from the project?

Hood: Anybody that’s grown up in Franklin is totally familiar with this story of a young man that left at the outset of the Civil War, when the brass bands and the parades and waving flags made a big fanfare that he was going off to a war that was going to last two or three months, and it lasted and it lasted and it lasted, and it tore the country apart. Four years later, that same young man, he was a war-torn veteran, and he was a captain in the Confederate Army, and he was leading a charge back into his father’s own farm, and his last words to the troops under his command were, “Follow me, men; I’m almost home.” And then, in his own back yard, he was shot no less than seven times, his body riddled with Union bullets. He was carried into the house that night, and two days later he died in the bed where he was born.

Hood: Anybody that’s grown up in Franklin is totally familiar with this story of a young man that left at the outset of the Civil War, when the brass bands and the parades and waving flags made a big fanfare that he was going off to a war that was going to last two or three months, and it lasted and it lasted and it lasted, and it tore the country apart. Four years later, that same young man, he was a war-torn veteran, and he was a captain in the Confederate Army, and he was leading a charge back into his father’s own farm, and his last words to the troops under his command were, “Follow me, men; I’m almost home.” And then, in his own back yard, he was shot no less than seven times, his body riddled with Union bullets. He was carried into the house that night, and two days later he died in the bed where he was born.

This was Captain Todd Carter, Confederate States of America, [of] the Carter House. The bullet holes are all still there. The little office building next to the Carter house, his father’s farm office, is arguably the most bullet-riddled building on American soil. It’s smaller than a one-car garage, and it’s got hundreds of bullet holes in it. Those types of things are all through this [book]. There are hundreds of anecdotes and stories—personal, colorful stories.

Historic Tennessee: Photographs by Robin Hood is available through the http://www.tennesseepreservationtrust.org/ “>Tennessee Preservation Trust and in bookstores throughout the state.

All photographs copyright (c) 2010 by Robin Hood. All rights reserved.