Chatting with the Enemy

American adventurer Mark Stephen Meadows gets to know the rebel terrorists of Sri Lanka

Artist, software designer, and global hitchhiker Mark Stephen Meadows was in Paris on September 11, 2001, expecting to fly home to the States the next day. Stranded by the grounding of U.S air traffic after the attacks, he wound up staying in Paris for months, watching from a distance as the U.S. became obsessed with terrorism. Meadows was puzzled and disturbed by the frenzy of fear, which seemed to be driven largely by the media. The overwrought portrait of terrorists offered by the press and the U.S. government needed to be countered, he thought, by a deeper understanding of the human beings who bore the label. In the spring of 2002, he decided to go to Sri Lanka, where Tamil rebels had been using terror tactics against the government since the mid-1980s. He was determined, as he puts it, to “do a little terrorist ethology.”

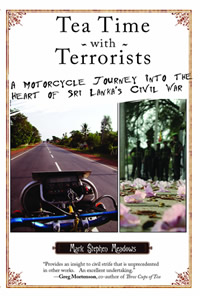

Tea Time with Terrorists: A Motorcycle Journey into the Heart of Sri Lanka’s Civil War is Meadows’s account of his experiences in Sri Lanka, but it’s not so much objective ethology as an exercise in good-natured, insightful, and often funny gonzo journalism. Meadows does indeed chat with terrorists, including Shankar Rajee, an early leader of the Tamil rebels who helped foster ties between Sri Lankan terrorists and extremist groups in the Middle East, but he devotes much of his book to the ordinary people he encounters. Whether he’s interviewing militants or puzzling over the proper etiquette at a ghost-banishing ceremony, Meadows reports with a keen eye and an open heart, never losing sight of the human factor behind all conflict.

Meadows answered questions from Chapter 16 by email in anticipation of his reading at Davis-Kidd Booksellers in Nashville on June 15.

Meadows answered questions from Chapter 16 by email in anticipation of his reading at Davis-Kidd Booksellers in Nashville on June 15.

Chapter 16: You have some pretty harsh words for mainstream journalism in Tea Time with Terrorists: “Corporate news is unclean, untrustworthy, and made to satisfy the agenda of those who can afford to buy the truth.” Is your book an antidote to that version of news? Do you consider it journalism?

Meadows: I certainly wouldn’t say that Tea Time is an antidote, but there are processes that I tried to follow which might offer us some clues as to a recipe for that antidote. It’s stuff anyone can do. But lemme digress for a second.

Don’t tell anyone, but Tea Time is ultimately a book about media. This notion of “Gossip Gone Gospel” is one of the balloons that I hope to puncture by pointing out that our only real method of alleviating fear is by learning for ourselves, and examining its cause. You have to do that with your two eyes, your two ears, your two hands. We can’t do that with broadcast news.

What is worse is that broadcast news and most “corporate media” seem to me to be largely designed to not just report on dangerous situations, but to actually create fear. As someone that’s been to many places where the news is being reported, if I’m there, and I read the news, and then I look around me, I see almost no correlation between what’s being reported and where I am. The magnifying lens of broadcast news tends to over-expand what is fearful, because that’s what makes those guys money. They kind of have to, you know? Nobody’s going to pay them for “Jennie’s Kitty Retrieved From Tree Next Door.” We pick up the news because we want to know if the Apocalypse is going to hit today. It’s something of a cross between survival instinct and a horror show, and we pay to watch it. And the corporate news folks have to keep that momentum going as best they can, otherwise they’re outta work.

So while Tea Time is not an antidote to what might be called the poisons of corporate news, the method of learning for ourselves and relying on our own experiences are. I hope people pick that outta the book. I hope that we can each put television and Internet news at arm’s reach and realize that, in fact, little Jennie’s kitty might, really, be more important than some guy in a cave twelve time zones away.

Chapter 16: In the course of discussing America’s so-called wars on drugs and terrorism, you write that religion may be more of a threat than either, and that “until an inventive politician finds a way to fund a War on Religion, our other wars will continue to extend themselves out into the thin and melting ether of global ethics.” Does religion inevitably promote conflict?

Meadows: Religion, perhaps, but monotheisms, certainly. This might be because in a monotheistic view of the world there are no avenues for negotiation—you’re either right or you’re wrong. You’re either with us or against us. (If someone says that to me, well, them’s fightin’ words!)

I like traveling in Buddhist and Hindu countries because even though I may be from another place, my visit is considered valuable to the people I visit. In that world, difference brings richness, foreigners are considered valuable, and it’s always acceptable to add more spice into the soup of the city. That’s a generalization, of course, and one that’s generally true in most of India and Sri Lanka, and much of Asia.

I like traveling in Buddhist and Hindu countries because even though I may be from another place, my visit is considered valuable to the people I visit. In that world, difference brings richness, foreigners are considered valuable, and it’s always acceptable to add more spice into the soup of the city. That’s a generalization, of course, and one that’s generally true in most of India and Sri Lanka, and much of Asia.

By contrast, I think that monotheisms—Judaic, Christian, Muslim—say that we have one way, and one way only. These iterations of monotheism (which gets rebooted every 500 years or so) seem to get more violent each time. It seems to be more important to defend The Faith with violence. (Muslims today don’t care for images of Mohammed, for example, and maybe the bombing in New York in early May was a result of what the South Park boys were up to—it took place out in front of their offices, after all. I’ll talk about this a bit in my lecture in Nashville.)

So, yes, I think that there is a link between monotheism and violence. And maybe religion in general.

Chapter 16: “Gossip gone gospel” is a phrase you use to talk about people’s prejudices and their ideological agendas, whether they are tourists, terrorists, or politicians. After all the traveling you’ve done and the various cultures you’ve encountered, do you think there’s a universal need for such gospel?

Meadows: Yes! Absolutely. Gossip and Gospel are both important parts of a community. They might be core to being human, even. To return to the media question you started with, what I suspect we now have, with television, and Internet (and other forms of automated broadcast media), is a strange proportion. The very important operands of culture, gossip, and gospel, have been abstracted in a manner that prevents us from gaining their value, as they become simultaneously more expensive. Our gossips and our gospels are now automated, broadcast, and sold to us, and that has drained them of the value that they had before the industrial revolution.

But I use the phrase “Gossip gone Gospel” to refer to a particular situation. Gossip and gospel, politics and religion, and oil and water are all things that don’t normally mix—unless you really stir the pot. They don’t mix well unless there’s a great deal of agitation. In other words, gossip and gospel are both important, and both generally kept separate, but in times when a population is afraid, during a war, during political unrest, during great ideological differences, such as we see in the U.S. today, the difference between them becomes hard to discern.

You can mix oil and water, you can mix gossip and gospel, and you can mix politics and religion, but you need a violent stirring to make it happen.

Chapter 16: You do some very risky things in the course of the book, from actually having tea with terrorists to brazenly asking a taxi driver where you can buy heroin. Did you wonder whether it was really worth the risk for the sake of a book? What’s the equation that makes the risk acceptable to you?

Meadows: It wasn’t for the sake of the book, but for the sake of the reader! In that case I am serving my reader with my life and my limb. I’m like a farmer that did the work to bring back the fruit. My job was to go there, see for myself, and report back. There was no alternative but to put my own life, limb, and ethics on the line; otherwise I don’t think the book would have had any credence to it. And it was worth the risk as I came out O.K. (tho my mom wasn’t too happy about it).

In terms of where to draw the line, I don’t think there is an equation. Most of it has to do with trusting people and being open to the notion that we do not live in a dangerous world. Of course, the only way I can prove such an absurd hypothesis is if I do equally absurd things!

Take hitchhiking. There is no equation. Only trust. If I’m hitchhiking, and someone pulls over (or if I stop to pick someone up), I just decide if it’s a good match on the fly. Intuition. I can always, at the last minute, say “No.” But that’s only happened to me once or twice in thousands of rides. On the other hand, I met my wife hitch-hiking. She picked me up in Corsica. There was no equation there, either. We just said “Yes!”

On a note there, some people have said to me, “Oh, but Come On, Mark. You’re a 6’2″ male! You have nothing to be afraid of!” Not only is this untrue in a world where we have guns, knives, and explosives, but this response neglects the other side of the equation in which I’m standing on the side of the road and everyone is driving by because they’re afraid to pick me up! A little old lady on the side of the road could hitchhike around in the world far more easily, far more safely, and with far more protection. In my experience, if a little old lady was hitchhiking, everyone and their auntie would pick her up and want to help her. That’s because we live in a world that’s pretty safe. The odds are for us. I just have faith in humans, and that faith, or confidence, or love, or whatever it is, comes from talking with some of the worst of them.

Chapter 16: There’s a recurring image in the book of people being trained, as the elephants are in Sri Lanka, with “crackers and sweets”—sometimes quite literally, as when Yasser Arafat gives sweets to Shankar Rajee and his fellow trainees at the PLO camp. You seem to be suggesting that people can be lured into almost anything with gentle manipulation. If that’s true, is there a remedy? What gives people the capacity to resist?

Meadows: I don’t know—I can’t even invent a stupid answer to that. One thing I note on a disturbingly similar level is how we are manipulated today in online media we each use. Consider Facebook or Google. Those online services give us little candies, little crackers, and we lumber along with them, never bothering to consider why they give us a free email account, why they pay to have their server search for us, why they are willing to give us 500mb of disk space. Well, there are answers of course, but I suspect this is a very dangerous interaction, as it effectively cuts the tendons that resist manipulation. With all your personal data in the system you are suddenly open to all kinds of manipulation. (Ask Mussolini, Stalin, or Hitler how.) So maybe the question is not “What gives us the capacity to resist?” but rather “What gives us the incapacity to resist?”

Chapter 16: Your experiences as a traveler and writer seem far removed from your work as a software designer. Do you see a connection between them?

Meadows: Exploration. I like solving hard abstract problems via specific solutions, and finding myself without resources, where I have to invent my way out. I’m a weird combination of a painter and a computer geek, so thinking visually lends itself well to making hard problems harder! I like confusing myself, I’m a bit of a nomad, and I like exploring, I guess.

Plus I got bored of software and wanted to try to do some work on something that mattered more to me than interface design.

Chapter 16: You were quoted at the online Hitchhiker’s Encyclopedia as saying, “Save a thousand dollars, quit your job, put your stuff in storage, and buy a plane ticket to a very poor country. Go there and ask the people that live there how you can help them.” Do you still think that’s a plan worth pursuing these days?

Meadows: Definitely.

My three rules of travel:

1) Get Lost.

2) Talk to Strangers.

3) Keep Your Shit Together.

Mark Stephen Meadows will appear at Davis-Kidd Booksellers in Nashville on June 15 at 7 p.m.