Child of the Green Routine

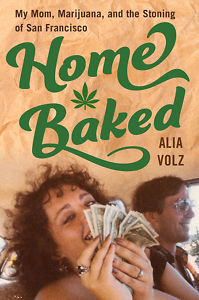

Alia Volz pays tribute to her mother’s enterprising marijuana brownie business in Home Baked

In Home Baked: My Mom, Marijuana, and the Stoning of San Francisco, Alia Volz crafts a loving portrait of Sticky Fingers Brownies, the empire of pot-laced edibles that her mother, Meridy, built amid the tumultuous events that rocked San Francisco during 1970s and 80s.

Arriving in San Francisco on the same day as Patty Hearst’s arrest, Meridy dove straight into the city’s counterculture. Described by her daughter as “a hedonist at heart,” Meridy was primed for mind-expanding pursuits. Although she’d had a brush with drug-related charges in her hometown, Milwaukee, Meridy’s life until then had been relatively “square” and middle class. San Francisco appealed to her wilder impulses, her “unquenchable yearning — for a grand romance, artistic greatness, her Yellow Brick Road.”

Needing to supplement her income as an illustrator, she chanced upon an opportunity that steered her life permanently down an unconventional path. An acquaintance who wanted to leave the city offered Meridy her small but crucial “magic brownies” sales turf at the Fisherman’s Wharf Art Market. She embraced the role of Brownie Lady and set out to expand her clientele.

Meridy didn’t seek customers on the street — a surefire way to get busted. She focused instead on the employees of local shops and offices. As her business grew to include “people working behind the scenes — the cooks and dishwashers, the back-of-house managers, the seamstresses and warehousemen,” Meridy relished the opportunity to learn how San Francisco operated: “There was something delicious about peering behind the façade of the City, like opening a mechanical clock to see the cogs dance.”

Meridy worked with numerous colorful, engaging collaborators, but none had greater impact on her life than Doug, Alia Volz’s father. Doug was an artist who had trained at the Berkeley Psychic Institute, specializing in chakra and aura readings. His spirituality and internal turmoil appealed to Meridy’s own intensity, which contained “a vulnerability that no amount of magic could shield.” Their stormy marriage fueled the business with combustible energy.

Doug’s contributions to Sticky Fingers included the decision to print original artwork on each week’s brownie bags. These images reflected events occurring in the city, as well as Meridy and Doug’s personal lives, and they became highly prized among Sticky Fingers customers. Many of these designs illustrate the book, adding dimension and whimsy to Volz’s story.

Volz marvels at her parents’ risky choices but doesn’t pass judgment on them. She was born into “the green routine,” when Sticky Fingers was thriving, expanding territory and generating reliable income. Though the family business was highly illegal, marijuana dealing provided the only safety and normalcy Volz understood. To her, the more conventional lives of other children seemed incomprehensible.

Volz marvels at her parents’ risky choices but doesn’t pass judgment on them. She was born into “the green routine,” when Sticky Fingers was thriving, expanding territory and generating reliable income. Though the family business was highly illegal, marijuana dealing provided the only safety and normalcy Volz understood. To her, the more conventional lives of other children seemed incomprehensible.

Charged with concealing her parents’ profession, lest they end up in prison, Volz held an outsized burden for a child so young. Volz acknowledges, “My parents’ secrets sometimes isolated me from other kids.” But she emphasizes that she was never neglected, that she “was fawned over, encouraged, welcomed into the conspiracy.” Volz sees the contrast clearly: “An outcast at school, I was inner-circle within the Sticky Fingers world.”

Home Baked pivots back and forth between the family’s personal story and the larger cultural and historical currents that wielded significant influence on their lives. This narrative structure pays off at various points in the book. We follow the ways that Meridy shifts her business strategies in order to keep skirting police detection, in response to changing practices and agendas of governmental agencies and political administrations. We learn how longstanding local San Francisco figures of this period — notably, Jim Jones and Harvey Milk — exerted their influence in the city for years before their legacies exploded into the national zeitgeist.

Most movingly, we feel Meridy and young Alia’s dismay and heartbreak as they make their regular neighborhood delivery rounds during the early years of AIDS. As healthy, luminous men all around them wasted away before their eyes, Sticky Fingers Brownies provided crucial relief from devastating symptoms when conventional medicine offered few options.

Stories like Meridy’s place the rapidly evolving legal and cultural status of all cannabis-related products into fascinating perspective. “The AIDS crisis is painful to conjure, painful to relive,” Volz writes. “Easier to let the past fade, to toke up and forget.” But Volz brings her point home with timely conviction: “There’s nothing superficial about fighting a plague.”

Volz has written a refreshing kind of family memoir — one that presents the messier truths of her family’s life without pushing to create martyrs and villains. During a time when huge swathes of our population are being asked to do some small part for the greater good of public health, stories of fallible but compelling lives like Meridy’s are especially welcome. Whether or not you have any particular interest in the fine details of marijuana as a subject, Home Baked will envelope you in its warm, generous heart.

Emily Choate holds an M.F.A. from Sarah Lawrence College and is the fiction editor of Peauxdunque Review. Her fiction and nonfiction have appeared in Mississippi Review, Shenandoah, The Florida Review, Tupelo Quarterly, Bayou Magazine Online, Late Night Library, and elsewhere. She lives near Nashville, where she’s working on a novel.