Chug-a-Lug

Max Watman’s rollicking history of moonshine includes a few tempting (if illegal) recipes

My wife and I recently spent an evening with old friends in Nashville, a couple we have known since graduate school. After dinner, our host pulled out an unmarked bottle of honey-colored liquid. It was, he informed us, superior homemade hooch, distilled by a friend in Louisiana and properly aged in a charred oak barrel.

I had last tasted white lightning about twenty years earlier, when a Tennessee farmer offered a pull from a plastic milk jug before granting me permission to explore a cave on his property. The clear liquid smelled like aircraft fuel and tasted like liquid fire, imparting an instant headache and a lingering fear of blindness. In contrast, the genteel moonshine my friend poured into my glass last summer tasted of caramel and oak, with a hint of roasted corn. It was as smooth as any ten-dollar-a-shot boutique bourbon from a big-city bar. Maybe smoother.

That Louisiana distiller is one of growing number of whiskey hobbyists—educated folks who dabble in liquor in the manner of home brewers and winemakers. Of course, one major difference between home brewers and moonshiners is that the U.S. government will let anyone make up to 300 gallons of beer per year, while distilling even an ounce of unlicensed liquor is a federal crime that can fetch serious fines and jail time. Being descended from Southern farm stock, I’m sympathetic to the notion that government has no business interfering with private individuals who wish only to preserve an early American craft for personal enjoyment. Not quite sympathetic enough to start a pot of sour mash bubbling in my basement—at least, not so far—but sympathetic enough to fantasize about it.

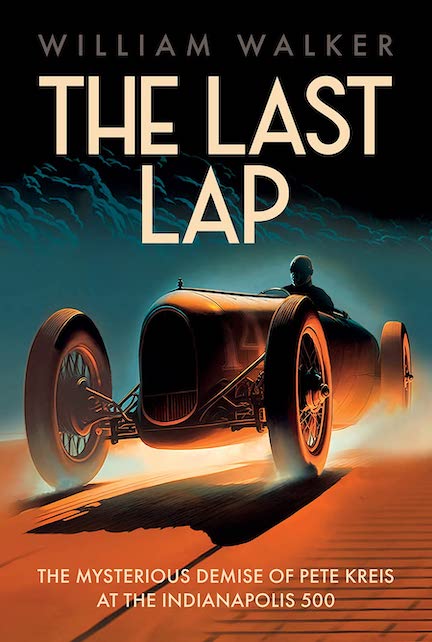

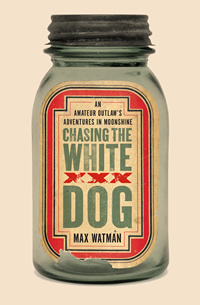

So it was with some delight that I picked up Max Watman‘s new book, Chasing the White Dog: An Amateur Outlaw’s Adventures in Moonshine. Watman is a journalist originally from Virginia who now lives in rural New York, and the book is partly a history of moonshine and partly a memoir about his own attempts to make some hooch. Here, then, was a writer who had lived the fantasy and a book that would educate me on the distiller’s art, perhaps providing evidence I could present to my wife that a small home still would not send us to jail or turn us into hillbillies.

So it was with some delight that I picked up Max Watman‘s new book, Chasing the White Dog: An Amateur Outlaw’s Adventures in Moonshine. Watman is a journalist originally from Virginia who now lives in rural New York, and the book is partly a history of moonshine and partly a memoir about his own attempts to make some hooch. Here, then, was a writer who had lived the fantasy and a book that would educate me on the distiller’s art, perhaps providing evidence I could present to my wife that a small home still would not send us to jail or turn us into hillbillies.

Well, mostly.

Watman does indeed carry readers from his awful first attempt at home distillation in a glass Erlenmeyer flask through a progressively more complex succession of small homemade stills, until he finally manages to produce a bottle of decent drink. He travels to his home in the Virginia hills to meet old moonshiners and old revenue agents, and explores the seamy urban underside of modern moonshine in Philadelphia and other cities. And he presents a fascinating history of illegal booze, one which is bound to the history of the United States in surprising ways.

Before 1791, Watman writes, “there had been no such thing as moonshine in America. Distilling, at any level, was legal and untaxed. Farmers didn’t register their still any more than they registered their plows, for distilling a harvest of grain was simply good farming. There are three key reasons for this. First, a couple of bushels of rye, each of which weighs 56 pounds, can be converted to 5 gallons of whiskey… . It’s easier to transport grain that has been stored as whiskey than it is to transport the raw product. Second, grain spoils, whiskey doesn’t. Third, whiskey is always worth more than the grain that went into it.”

And, he adds, perhaps unnecessarily: “As if that weren’t enough, let us not forget the bonus: you can drink the whiskey.”

As Watman explains, despite this simple country wisdom, the young democracy sought to impose its first tax of any sort on whiskey, setting off the Whiskey Rebellion and creating a subculture of illegal spirits that grew with the nation and continues to thrive. The Internal Revenue Service was born from government efforts to collect whiskey taxes, and the early revenuers were as often more interested in getting their cut of the profits than enforcing the law. The Civil War spawned generations of Southern moonshiners who resented paying taxes to a conquering nation. Prohibition made criminals of not only the makers of hooch but the consumers as well, forcing a large percentage of the American population into willful disregard of any laws involving liquor— a disregard that did not die out with the repeal of Prohibition.

While the history Watman presents is undeniably fascinating—and often funny—it is unfortunately a back-room gin joint sort of history, one that might or might not stand up in the light of day. For example, consider Watman’s account of Orville E. Babcock, the highest of many federal officials implicated in the St. Louis Whisky Ring, a corrupt collusion of tax collectors and distillers: “Babcock met his fate aboard the Pharos, a sea-worthy, two-masted schooner. A few years later, she would rescue the ship Sybil when that one encountered a severe hurricane near Dog Rock, off the Florida Keys on November 12, 1857,” Watman writes. “On June 3, 1885, the Pharos was under the command of Captain Anderson. She was lying off Mosquito Inlet, near Daytona, where Stephen Crane clung to a lifeboat after the Commodore went down on her way to Cuba.” Watman notes that Babcock was “overseeing the building of a lighthouse that would fill an especially long gap on the coast between Cape Canaveral and St. Petersburg,” when he insisted on being put aboard a small boat in the rough seas of the inlet and promptly drowned.

While the history Watman presents is undeniably fascinating—and often funny—it is unfortunately a back-room gin joint sort of history, one that might or might not stand up in the light of day. For example, consider Watman’s account of Orville E. Babcock, the highest of many federal officials implicated in the St. Louis Whisky Ring, a corrupt collusion of tax collectors and distillers: “Babcock met his fate aboard the Pharos, a sea-worthy, two-masted schooner. A few years later, she would rescue the ship Sybil when that one encountered a severe hurricane near Dog Rock, off the Florida Keys on November 12, 1857,” Watman writes. “On June 3, 1885, the Pharos was under the command of Captain Anderson. She was lying off Mosquito Inlet, near Daytona, where Stephen Crane clung to a lifeboat after the Commodore went down on her way to Cuba.” Watman notes that Babcock was “overseeing the building of a lighthouse that would fill an especially long gap on the coast between Cape Canaveral and St. Petersburg,” when he insisted on being put aboard a small boat in the rough seas of the inlet and promptly drowned.

There are several problems with this passage. The Sybil sank nearly thirty years before the time in question, not “a few years later.” Stephen Crane had his adventure in the Mosquito Inlet in 1897, twelve years after Pharos was there. A coastal gap “between Cape Canaveral and St. Petersburg” would be long indeed, since the former is located along the Atlantic Ocean and the latter on the Gulf of Mexico. (Most likely, Watman means St. Augustine, not St. Petersburg.) Any one of these errors might be laid off to a minor lapse in copy-editing, but so many in such close proximity call into question the historical value of the passage; other historical passages are similarly plagued with error.

Fortunately, history is only part of Watman’s story. His first-person adventures in distilling, as well as his efforts to meet “serious” moonshiners, to drink in dangerous ghetto “shot houses,” and otherwise dive into the world of modern moonshine all carry a ring of truth and a wealth of detail. His reporting and innate sense of comic narrative shine in these sections. He may be the sort of historian who never lets facts stand in the way of a good story, but in researching this book, Watman has found a heck of a good story. In those places where he is part of it himself, the story flows like the amber liquid my friend poured in Nashville.

Despite a few missteps, both spirituous and literary, Watman ultimately serves up a palatable concoction, one with a satisfying—and thoroughly illicit—burn.