Citizens of the World

Marge Piercy talks with Chapter 16 about poetry, fiction, memoir, and writing as a political act

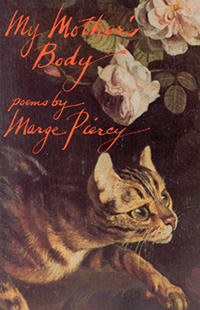

Marge Piercy’s productivity and accomplishments are nothing short of astounding. She has published seventeen novels in genres as diverse as science fiction and historical fiction, including The New York Times bestseller Gone To Soldiers. As if that weren’t enough, she has also published seventeen volumes of poetry and a memoir.

Piercy’s work does not shirk from addressing tough political and social issues. As one critic from The Boston Globe commented, “Marge Piercy is not just an author, she’s a cultural touchstone. Few writers in modern memory have sustained her passion, and skill, for creating stories of consequence.” Piercy’s cultural and literary importance is confirmed by four honorary doctorates and the attention of national media, including Bill Moyers’s PBS specials, Garrison Keillor’s A Prairie Home Companion, Terri Gross’s Fresh Air, and The Today Show.

Sex Wars (William Morrow, 2005), Piercy’s latest novel, features real-life Victoria Woodhull, a feminist, suffragist, and proponent of free love who was the first woman to run for president. Her forthcoming work is a second volume of selected poems, titled The Hunger Moon, that will be published in February by Knopf. She answered question from Chapter 16 by email prior to her public reading in Knoxville on October 17.

Chapter 16: In your memoir, Sleeping with Cats, you directly address the fallibility of memory: “How can I not trust memory? It is as if I were to develop a mistrust for my right hand or left foot. Yet I am quite aware that my memory is far from perfect.” What have been the results for you of writing on topics that were “foggy” or topics that you resisted?

Chapter 16: In your memoir, Sleeping with Cats, you directly address the fallibility of memory: “How can I not trust memory? It is as if I were to develop a mistrust for my right hand or left foot. Yet I am quite aware that my memory is far from perfect.” What have been the results for you of writing on topics that were “foggy” or topics that you resisted?

Piercy: In the memoir workshop my husband Ira Wood and I teach regularly, I conduct an exercise in which participants strengthen their sensual memory and learn to move from what they remember to what they may have forgotten. This is a technique I used to recover scenes from my past that I had forgotten or could not clearly recall at first. Events I resisted remembering I simply persisted and insisted to myself that I had to proceed into what I found painful. There was a lot of that, but the most painful events to recall are often quite important, so forcing yourself through remembering and writing about them is necessary to a memoir. The writing about traumas also distances them a bit, which is helpful in the long run.

Chapter 16: You also have mentioned that your grandmother and mother were your muses. What did you learn as a writer from them, especially in the way they would tell the same story?

Piercy: My mother, my aunt Ruth who was between my mother and me in age, and my grandmother had very different viewpoints on the same events. That was how I learned about viewpoint. Not all their stories were the same, of course. My grandmother told me many myths of Ashkenazi Jewish culture, especially women’s culture: Lilith, the Golem, for instance, and tales of women who did not pay attention to superstitions and suffered the consequences. My mother told me stories of her previous marriages and experiences and her view of her childhood. Aunt Ruth told me about working for the Navy and her successes in bowling and golf. But when they told the same story, usually of events in the large Bunnin family, then my grandmother’s tales were moralistic, intended to show how important it was to behave as a proper Jewish woman or man. My mother’s stories were more romantic and sensational. Aunt Ruth tended to the analytical, as if every event were a miniature detective story in which she deduced motives and intentions. It was early and important training both in the art of the narrative and in how different people view the same event in totally personal ways.

Chapter 16: Do you have some general principles that guide you in deciding what subject matter is better suited for a specific genre? You have said that “narrative is about time.” What’s the equivalent to poems and memoirs?

Chapter 16: Do you have some general principles that guide you in deciding what subject matter is better suited for a specific genre? You have said that “narrative is about time.” What’s the equivalent to poems and memoirs?

Piercy: Memoir is an attempt to find a thread on which to create a narrative out of part of a writer’s life. No autobiography is comprehensive, or it would take as long to write as it did to live, and what would result would be rambling, incoherent, and boring. A memoir selects one aspect, one narrative out of all the events of a life. It does not attempt to be complete but rather to pick out—of all the myriad events and decisions and accidents of a life—some narrative that makes a pattern and makes sense.

You can’t possibly mistake an idea for a novel for an idea for a poem. It is as if you were comparing the geography of a country with the map of a city or village. Even when a poem is a narrative, it is far more intense, selective, far more reliant on images, rhythms, oral effects than any story. Whether a poem is lyrical or narrative or imagistic, it is obviously a poem. Poems are still an oral form for most of us, and thus poems may lie on the page in black and white, but they do not come to life until they are spoken out loud or in the mind. Poems are created of sounds and silences. The sound qualities of a poem are extremely important. There are poems that look OK on the page, but if you try to speak them, they come apart like beads from a broken necklace.

Chapter 16: We are seeing a number of novels that merge the historical with the literary as you do in Sex Wars. I’m thinking of Barbara Kingsolver’s The Lacuna, Michael Knight’s The Typist, and Michael Chabon’s The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier and Clay, to name just a few. How do you negotiate that line between revealing the factual truth and creating new scenes and situations that the real-life characters never experienced?

Piercy: Americans by and large have lost a sense of history. I had a student in a junior women’s studies class gig ask me, when I mentioned the Vietnam War, “Is that the same as the Civil War?” Anything more than five years in the past is sloughed off. To make history vivid and real and to identify threads in it that seem to the writer relevant to the present is the purpose of historical fiction (excluding bodice rippers, of course).

The past is as chaotic as the present, so the writer selects certain events to concentrate on, to create a narrative structure. Most history used to be just kings and queens, generals and presidents, battles and successions. Some historians now try to study everyday life of the various classes, including the history of women, who were largely absent from previous history unless they were queens, famous courtesans, or infamous victims. It is recreating that sense of daily life that is important to me in my historical novels, as well as elucidating the pressures of history so that we understand how we come to be where we are. Often I am plucking out the roles of women in history usually seen as male, such as the French Revolution in City of Darkness, City of Light.

Facts are not so easy to ascertain as you imagine. When I was writing Gone to Soldiers and was telling of a particular convoy that was savagely attacked by U-boats, research here and in England could not even agree on what boats were in the convoy and which were sunk. In carrying out my research for Sex Wars, I found there is considerable mystery surrounding exactly how Elizabeth Cady Stanton died. I learn what I can from research (my research for a number of my novels is seven or eight times as long as the resulting novel), and I try to enter my major protagonists so that I can see the world through their eyes. All biography involves making judgments about what was true in an individual’s life and how the social and political and economic forces impacted that person. So does historical fiction.

Facts are not so easy to ascertain as you imagine. When I was writing Gone to Soldiers and was telling of a particular convoy that was savagely attacked by U-boats, research here and in England could not even agree on what boats were in the convoy and which were sunk. In carrying out my research for Sex Wars, I found there is considerable mystery surrounding exactly how Elizabeth Cady Stanton died. I learn what I can from research (my research for a number of my novels is seven or eight times as long as the resulting novel), and I try to enter my major protagonists so that I can see the world through their eyes. All biography involves making judgments about what was true in an individual’s life and how the social and political and economic forces impacted that person. So does historical fiction.

For instance, there is no actual record of what Comstock’s wedding night was like, but having entered with some difficulty but great persistence into his mind and his world view and having studied Margaret, I had a pretty good idea what to write about it. Besides, it was fun.

Chapter 16: You have been a strong voice in many political issues of your lifetime: the Vietnam War, women’s rights, the current war in Iraq. Your writing takes on these issues and does not shirk from the duty of writing as a political act. Your latest collection of poems, The Crooked Inheritance, features poems about healthcare and Iraq for example. What are your thoughts on the responsibilities of writers as activists?

Piercy: Writers are citizens the same as any other citizens, and thus responsible for supporting their government when it does good things and opposing their government when it does evil or foolish things. As a Jew, I obviously learned from the German example that if you don’t take an active role and if you don’t observe carefully what your government is doing, you can end up dead.

Chapter 16: At the same time, it is not an easy task to write political work. Poet Robert Hass has said that the key is to “write very honestly about the actual dilemmas, which means thinking about them clearly, which means not flattering yourself that you know what the solutions are … .” What are some of your strategies for bringing art to your policy critiques?

Piercy: There is no difference whatsoever in crafting a good political poem or a good nature poem. Nature poems that are not well written can end up banal, cute, or overly anthropomorphized. Political poems that are not well written can end up as rhetoric. The idea that there is something odd about writing political poems is a modern heresy nourished by those who don’t want anything to change except their status and power in a society where one in seven people live in poverty, as do one in five children. Catullus would not have understood that there was something suspicious or naïve about writing poetry with political content, nor would have Milton, Shakespeare, Dryden, Pope, Shelley, Byron, etc. Politics is simply a part of our lives as much as love, children, death, and holidays. Craft is the same whether you’re writing about daffodils or bombs.

Chapter 16: What are you currently writing?

Piercy: Lots of poetry, introductions to the reissue of my second and sixth novels, Dance the Eagle to Sleep and Vida that PM Press is bringing out next fall. I have begun a novel I hope to get back to in November after a very hectic summer with five readings of my own work, reading Yevtushenko’s English and introducing him, a three-day memoir lab with Ira Wood, and a juried intensive poetry workshop in Wellfleet that lasted a week.

Moreover, there are elections going on, and we had a fight on our hands this spring when the Seashore decided to poison crows. I have a relationship with the crows who live on my land but range widely. Crows are very intelligent social creatures who have no trouble telling individuals apart, even if we can’t do the same with them. We grow all our own vegetables, and this was a bumper year with ongoing harvest, canning, freezing, dehydrating, root-cellering. We barter our vegetables for various sorts of protein: shellfish, fish, organic and humanely grown eggs, and recently for some chainsaw work. Our tomatoes are famous. Mostly heirlooms. Writing is the core of my life, but there’s always a lot else going on. I’m acting in my village on various committees and activities.

Moreover, there are elections going on, and we had a fight on our hands this spring when the Seashore decided to poison crows. I have a relationship with the crows who live on my land but range widely. Crows are very intelligent social creatures who have no trouble telling individuals apart, even if we can’t do the same with them. We grow all our own vegetables, and this was a bumper year with ongoing harvest, canning, freezing, dehydrating, root-cellering. We barter our vegetables for various sorts of protein: shellfish, fish, organic and humanely grown eggs, and recently for some chainsaw work. Our tomatoes are famous. Mostly heirlooms. Writing is the core of my life, but there’s always a lot else going on. I’m acting in my village on various committees and activities.

Chapter 16: What is happening in our current political climate that we should be paying attention to more closely? We know what’s making headlines, but what do you see happening that is quieter than the headlines but equally as important?

Piercy: Afghanistan is a disaster. It is not a country but a collection of tribal states overseen by opportunistic leaders. Alexander the Great couldn’t conquer it, neither could either of the Khans, neither could the British, neither could the Russians. Every invading army has some successes and then everything falls apart. We don’t belong there, and we cannot win. We can only continue to bleed lives and money down a very large old hole. We refuse to learn from history and we believe our own propaganda that we are unique and out of history. This exceptionalism, and this attitude [of] applying manifest destiny to the world is similar to what caused Napoleon no end of trouble finally.

The rich and powerful have no patriotism, although they use it against everyone who tries to make our country more just and more equal. Multinational corporations have no loyalty to our country or any of us. We are the slaves of media that feed us slogans that work against our real interests. We have been persuaded the most important thing in the world is to be skinny and have flat abs, something that ninety of the population will never attain and cannot, instead of trying to learn useful things and pay attention to what’s really happening. We the people judge ourselves and others by two criteria: how much do you weigh and how many new things can you purchase? No religion in the world except perhaps the Cargo Cult would recommend that as a philosophy.

Women have gained a certain amount, but only slaves cannot control their bodies. If we lost the right to choose to bear or not bear children, we will be enslaved again. I lost a close friend to a botched illegal abortion and had to abort myself at eighteen, so choice means a great deal to me. More women used to die from abortions than in our foreign wars. I remember all that. It isn’t rhetoric to me, but a matter of women dying from political choices.

Also many of the gains for women are only for middle-class and upper-class women, leaving other women still without safety, without the means to lead a fulfilled life. I never forget that the choices open to me as a woman were better than those of my grandmother and my mother, but that for many women, there are few options and little choice. Shall I buy cereal and milk for my kids or pay the electric bill? No one should have to live with such decisions to make every month. And for the elderly without money, shall I actually take the medicine for my diabetes or pay for oil to heat my house this winter? With so many people faced with such decisions, we are not a just society.

On October 17, Marge Piercy will read from “The Art of Blessing the Day: Poems of Ritual and Remembrance,” at Temple Beth El of Knoxville, 3037 Kingston Pike, at 7 p.m. On October 18, she will give an informal author chat at 3 p.m. in 1210-1211 McClung Tower on the University of Tennessee campus. Also on October 18, a public reading, “Poetry of Jewish Identify” will take place at 7 p.m. in the University Center auditorium. All events are free and open to the public.