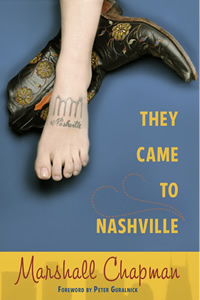

City of Dreamers

Marshall Chapman talks with fifteen celebrated musicians about their earliest days in Nashville

“Nashville has always been a magnet for dreamers, iconoclasts, poets, pickers, and prophets from all over,” the singer/songwriter Marshall Chapman writes in the prologue to her new book, They Came to Nashville, a collection of interviews with noteworthy musicians about their earliest days in Music City. In the book, Chapman sits down to chat with fifteen old chums and close acquaintances, including many who have shared a stage or recording studio with her over the years. They range from the legendary—Kris Kristofferson, Emmylou Harris, John Hiatt—to relative newcomers like Miranda Lambert and Terri Clark. Each chapter begins with an essay by Chapman and ends with an interview—though the Q&A sections read more like intimate conversations between longtime friends than glossy celebrity journalism.

Chapman herself, a resident of Nashville for some forty-plus years, hails from Spartanburg, South Carolina, where she grew up in a well-heeled family and fell in love with music. A Vanderbilt education was her ticket to Nashville, and it wasn’t long before she was breaking away from campus to go to parties where some of the city’s best up-and-coming talents lurked late into the night. (At one such gathering, in a Ramada Inn on James Robertson Parkway, Chapman first heard Kris Kristofferson sing “Me & Bobby McGee.”) Her first book, Goodbye, Little Rock and Roller, chronicled her misadventures in the thick of Nashville’s “outlaw” era. Which is all to say: Chapman has unassailable cred as a Music City insider, and as such she’s decidedly in the sweet spot to dish up story after story about the talented folks who have seen their stars rise in Nashville—and have in turn burnished the Nashville brand.

But where Goodbye, Little Rock and Roller got raucously down and dirty in Chapman’s accounts of her own, and others’, exploits and excesses through the freewheeling 70s, this new book takes a mellower tack, and turns a deaf ear to the siren song of gossip. Clearly, Chapman deeply respects all the assembled artists, and she’s not out to provoke or trick them into revealing more than they bargained for; it’s simply not her objective. She maintains a view-from-the-inside charm while pursuing an ultimately friendly mission, as she describes it in the prologue: “Lately, I’ve been thinking a lot about this—why anyone would pick up and leave everything they’ve known to pursue a dream. What were they looking for? What were they running away from? What did they imagine would happen?”

But where Goodbye, Little Rock and Roller got raucously down and dirty in Chapman’s accounts of her own, and others’, exploits and excesses through the freewheeling 70s, this new book takes a mellower tack, and turns a deaf ear to the siren song of gossip. Clearly, Chapman deeply respects all the assembled artists, and she’s not out to provoke or trick them into revealing more than they bargained for; it’s simply not her objective. She maintains a view-from-the-inside charm while pursuing an ultimately friendly mission, as she describes it in the prologue: “Lately, I’ve been thinking a lot about this—why anyone would pick up and leave everything they’ve known to pursue a dream. What were they looking for? What were they running away from? What did they imagine would happen?”

They Came to Nashville doesn’t always come up with surprising or remarkable answers to those questions, but it does offer rare, honest glimpses of the hand-to-mouth, humble years that typify the songwriter’s indoctrination into the Music City hustle. Readers unfamiliar with this world may be disappointed to discover that no biographical broad strokes and career highlights frame the discussions. Chapman’s focus is much tighter, and often much more personal, than the typical celebrity profile’s—which at once makes possible some of the book’s liveliest material and, to a slight degree, narrows its appeal.

In one of the strongest chapters, Rodney Crowell recalls his first three months in Nashville, when he was essentially homeless, sleeping atop a picnic table beside Percy Priest Lake. Later, he lived in a “condemned building on Music Row… [with] one big room and a bathroom and a kitchen … and holes in the walls bigger than I was.” He also reminisces about the time he and Chapman spent working at the old TGI Friday’s on Elliston Place, where they met. Each was intimidated by the other: “I mean, here was this gorgeous Amazonian woman, who … seemed incredibly capable at your job up there as greeter,” Crowell says. Chapman, in turn: “I wanted to be a hippie hanging out in the park. I was thinking, ‘That guy over there [bussing tables] is a real artist.”

As an interviewer, Chapman is both meticulous and digressive. She’s bent on certain details, asking each and every interviewee, for instance, what sort of vehicle—plane? car?—brought him or her to the city for the very first time. In other ways, she keeps her subjects on a loose leash, happy to chase a good tangent or two, ever conversational. She shares many stories about how she’s crossed paths with these individuals over the years, but ultimately she’s committed to the book’s theme: to learning about her Music City comrades from a fresh angle.

As an interviewer, Chapman is both meticulous and digressive. She’s bent on certain details, asking each and every interviewee, for instance, what sort of vehicle—plane? car?—brought him or her to the city for the very first time. In other ways, she keeps her subjects on a loose leash, happy to chase a good tangent or two, ever conversational. She shares many stories about how she’s crossed paths with these individuals over the years, but ultimately she’s committed to the book’s theme: to learning about her Music City comrades from a fresh angle.

Suitably, They Came to Nashville closes with Chapman’s story of riding on Willie Nelson’s tour busy for a few days, basking in the strange glow of “Willie World” and trying, but ultimately failing, to get the interview she wants. What she does get are some very brief, written responses to her seven stock questions. But her account of the adventure itself has an exuberant, unpretentious quality, making it easily one of the highlights of the book even without an in-depth interview.

They Came to Nashville may be most eagerly devoured by industry folks—those who’ve rubbed shoulders with its subjects, or who happen to live and breathe the musician’s life themselves. As such, it would make a worthy gift for anyone with more than a passing interest—or role to play—in Nashville’s music biz. But its breezy storytelling, low-key candor, and glimpses of the Nashville that was—the gritty Lower Broad of the 70s, the many landmarks now long gone—make it an evocative portrait of Nashville any local reader would welcome.

To read an interview with Marshall Chapman, click here. To read an excerpt from They Came to Nashville, click here.