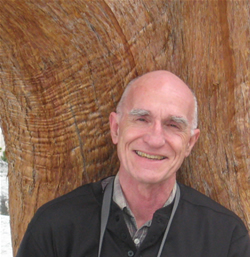

Compassionate Crusader

Author and environmentalist Scott Russell Sanders talks with Chapter 16

”A good book appeals to what is best in us,” Scott Russell Sanders has said, and his many fiction and nonfiction titles certainly call to our better angels. In his recent books, A Private History of Awe, which was nominated for the Pulitzer Prize, and A Conservationist Manifesto, Sanders examines such issues as environmental responsibility, social justice, the interrelatedness of geography and culture, and spiritual yearning.

Born in Memphis and reared in Ohio, Sanders is a Distinguished Professor Emeritus of English at Indiana University, where he taught from 1971 to 2009. The recipient of numerous awards, he was recently named winner of the prestigious 2011 Cecil Woods Award for Nonfiction from the Fellowship of Southern Writers, which will be presented during the biennial Conference on Southern Literature to be held in Chattanooga April 14-16. Sanders is also slated to headline this year’s Wendell Berry Lecture Series, an event on April 13 designed to raise environmental awareness and support urban forestation, sponsored by the Nashville Tree Foundation. In a recent email exchange with Chapter 16, Sanders discussed, among other things, his vision for a culture based on caretaking rather than consumerism.

Chapter 16: Your work comes highly recommended by noted environmentalist Wendell Berry, for whom this event is named. Aside from the environmental concerns you share, how do you see your literary mission as overlapping his, if at all? Do the two of you know each other in real life?

Sanders: Wendell Berry’s writing has been nourishing me for forty years. I’ve known him in person for nearly that long, since working up my nerve to ask if I could visit him at his home on the Kentucky River with my wife and our young children in the summer of 1975. Wendell and his wife Tanya received us graciously and talked with us through most of a Sunday afternoon. My only claim on their hospitality was that Wendell’s essays, stories, and poems had given me a clearer sense of my own calling as a writer. He helped me to see the importance of community and place, the role of culture in shaping our treatment of the land, and the power of literature to illuminate our lives. He also demonstrated that it is possible to make important art without living in one of the celebrated centers of cultural and economic power.

Sanders: Wendell Berry’s writing has been nourishing me for forty years. I’ve known him in person for nearly that long, since working up my nerve to ask if I could visit him at his home on the Kentucky River with my wife and our young children in the summer of 1975. Wendell and his wife Tanya received us graciously and talked with us through most of a Sunday afternoon. My only claim on their hospitality was that Wendell’s essays, stories, and poems had given me a clearer sense of my own calling as a writer. He helped me to see the importance of community and place, the role of culture in shaping our treatment of the land, and the power of literature to illuminate our lives. He also demonstrated that it is possible to make important art without living in one of the celebrated centers of cultural and economic power.

Chapter 16: In what ways does your environmental activism inform your fiction writing?

Sanders: In books such as Wilderness Plots and Bad Man Ballad, I have sought to understand how the history of American settlement—including the displacement or slaughter of native people, enslavement of African people, wholesale killing of animals, and the transformation of the continent through deforestation and plowing and industrialization—has shaped our attitudes toward the land. In books such as Terrarium and The Engineer of Beasts, I have projected current technological trends into an imagined future as a way of speculating about the environmental and social consequences of our present way of life. Right now I am at work on a novel, set in our own time, that features a protagonist who aspires to help restore damaged ecosystems and to save endangered species through work as a conservation biologist. I have also written about the period of wilderness settlement through a series of picture books for children, such as Aurora Means Dawn and Warm as Wool, and I have invited children to explore the near-by world of nature in picture books such as Meeting Trees and Crawdad Creek.

Chapter 16: With the media providing what seems like round-the-clock bad news, I hear more and more people choosing to turn a deaf ear to such reports, or to ignore the urgent need to change that such stories imply: I only have one life to live; let me live it attending to my own back yard, goes the refrain. What do you say to people who have reached this state of hopelessness?

Sanders: I understand despair, because nearly everything I love in the world is under assault. That’s the reason I wrote a book called Hunting for Hope. If hope were easy to come by, one wouldn’t need to go looking for it. One antidote to hopelessness is to do something useful—for your family, your neighbors, your community, or the Earth. No matter how dire the news may be, good work is always possible. Plant a garden or a tree; take a child for a walk; make music or bread; study nature; volunteer for a local organization; help an illiterate person learn to read. We’re not called to solve all the world’s problems; we’re called to act in light of our deepest values, to protect and nurture the things and places and people we love.

Chapter 16: Similarly, can you give Chapter 16’s readers a crib sheet of the most effective comeback to someone who, for political or business reasons, actively opposes environmental protections that would, for example, curb carbon emissions or ban offshore drilling?

Sanders: It’s no surprise that many people refuse to accept any constraints on their behavior—on what they consume, on the damage they cause. Selfishness and short-term thinking come naturally to human beings. A concern for the wellbeing of other people, other species, future generations, and the Earth has to be learned. If the person who rejects all forms of environmental protection calls himself a conservative, ask him what he wishes to conserve. If the person declares herself to be religious, ask her what she regards as holy, and how she understands the responsibilities of stewardship. If the person is a parent or grandparent, ask what sort of world we should leave for our children and grandchildren. If the person professes a love for beauty, suggest that everything we know about beauty has been learned from nature. If the person cares only about money, ask what good it will do to be financially rich in an environmentally and socially impoverished world.

Sanders: It’s no surprise that many people refuse to accept any constraints on their behavior—on what they consume, on the damage they cause. Selfishness and short-term thinking come naturally to human beings. A concern for the wellbeing of other people, other species, future generations, and the Earth has to be learned. If the person who rejects all forms of environmental protection calls himself a conservative, ask him what he wishes to conserve. If the person declares herself to be religious, ask her what she regards as holy, and how she understands the responsibilities of stewardship. If the person is a parent or grandparent, ask what sort of world we should leave for our children and grandchildren. If the person professes a love for beauty, suggest that everything we know about beauty has been learned from nature. If the person cares only about money, ask what good it will do to be financially rich in an environmentally and socially impoverished world.

Chapter 16: Some critics have observed that parts of A Conservationist Manifesto seem to be aimed at conservative Christians. What links do you see—or would you like to see—between faith and conservationism?

Sanders: I do hope that A Conservationist Manifesto speaks to Christians and other people of faith. That is why I wrote about the ecological implications of certain Bible stories and teachings. That is why I framed conservation as primarily an ethical issue. There are Christians who focus entirely on personal salvation, ignoring the needs of their neighbors, and dismissing earthly life as a husk to be cast aside. But that seems to me a tragic betrayal of the instruction to love God—and therefore God’s Creation—and to love our neighbor. A faithful person realizes that we are guests in this life; we are not the owners or rulers of Earth. Of course we need to use the things of the Earth in order to live, but we should do so lovingly, carefully, and respectfully.

Chapter 16: How do you think Japan’s nuclear tragedy will affect advocates of nuclear power?

Sanders: Generating electricity through the use of nuclear power has been a folly from the beginning. Promoting the so-called “peaceful atom” was conceived after World II as a way of reassuring the public about the safety of the nuclear weapons program, which has been and continues to be the most lethal project in human history. Seventy years after the earliest fission experiments, we still have no idea what to do with the radioactive waste. The nuclear industry has never been economically viable; it has required heavy government subsidies at every stage from research to waste storage to insurance protection to decommissioning of outdated plants. Uranium mining has condemned many workers to early deaths and has left vast areas of land desolate. By way of leaks, spills, meltdowns, gas releases, some accidental and some deliberate, countless people have been exposed to dangerous levels of radioactivity. The potential effects of earthquakes, power outages (and consequent loss of coolant), and human errors are catastrophic, as recent events in Japan have demonstrated. Building new nuclear power plants makes sense only for the companies and investors that would make billions of dollars from the undertaking. It makes no sense whatsoever for the rest of us.

Sanders: Generating electricity through the use of nuclear power has been a folly from the beginning. Promoting the so-called “peaceful atom” was conceived after World II as a way of reassuring the public about the safety of the nuclear weapons program, which has been and continues to be the most lethal project in human history. Seventy years after the earliest fission experiments, we still have no idea what to do with the radioactive waste. The nuclear industry has never been economically viable; it has required heavy government subsidies at every stage from research to waste storage to insurance protection to decommissioning of outdated plants. Uranium mining has condemned many workers to early deaths and has left vast areas of land desolate. By way of leaks, spills, meltdowns, gas releases, some accidental and some deliberate, countless people have been exposed to dangerous levels of radioactivity. The potential effects of earthquakes, power outages (and consequent loss of coolant), and human errors are catastrophic, as recent events in Japan have demonstrated. Building new nuclear power plants makes sense only for the companies and investors that would make billions of dollars from the undertaking. It makes no sense whatsoever for the rest of us.

Chapter 16: In your 1991 book, Staying Put: Making a Home in a Restless World, you argue for a life “firmly grounded in household and community.” Twenty years later, do you still see the traditional family as a viable model for stability and growth?

Sanders: Households may consist of a husband and wife and their offspring, as mine did while my children were growing up. My wife and I both grew up in such households, and our two children have married and brought their own children into the world. But households—and families—can take many forms, including same-sex couples, childless couples, single parents, roommates sharing expenses, elderly friends, numerous relatives, and so on. I don’t believe there is only one true or right form of the family. What matters is that it provides love and nurture. Humans are social animals; we need one another in order to be whole and healthy and sane. Family—in whatever form it may take—is the first community that most of us experience. It is where we begin to learn to be human. But the family in isolation from larger social networks may become pathological, or at least impoverished. So I do not draw a sharp boundary between the household and the community.

Chapter 16: You’re a Southern-born Midwestern writer. Do you see your own body of work as fitting more easily into one region’s traditional concerns than the other?

Sanders: Although I was born and spent my early years in Tennessee, and am descended from generations of Southerners on my father’s side (he was from Mississippi), I did most of my growing up in the Midwest, and I have spent my working life here. What I have derived from my Southern background, I suppose, is a heightened concern about the legacy of slavery and the continuing effects of racism in our society. The civil-rights movement affected me profoundly, in part because I was shocked by television images of whites abusing black people who were peacefully seeking the same rights that whites enjoyed.

Sanders: Although I was born and spent my early years in Tennessee, and am descended from generations of Southerners on my father’s side (he was from Mississippi), I did most of my growing up in the Midwest, and I have spent my working life here. What I have derived from my Southern background, I suppose, is a heightened concern about the legacy of slavery and the continuing effects of racism in our society. The civil-rights movement affected me profoundly, in part because I was shocked by television images of whites abusing black people who were peacefully seeking the same rights that whites enjoyed.

Overall, however, I have been more concerned with themes that may be thought of as Midwestern—how we use the land, the quality of life in small towns and rural communities, the beauties and patterns of nature, the role of religion in culture, the clash between imported ideas and wilderness. Because of the Civil War, we’re accustomed to thinking of the South as a tragic landscape. But I would argue that the Midwestern landscape is also tragic, although for different reasons. In all of America, this is the terrain most thoroughly transformed to suit human purposes—mainly for agriculture, but also for industry and mining. In just over two centuries of exploitation, we have spent much of its accumulated wealth—eroding the fertility of our soils, plowing our grasslands, leveling our forests, poisoning and damming our streams, dramatically reducing our biodiversity. As a writer, I have tried to understand the cultural roots of this squandering, and to envision a way toward healing and renewal of the land, our communities, and our way of life.

Scott Russell Sanders will speak on April 13 in Montgomery Bell Academy’s Paschall Theater at 4001 Harding Pike, Nashville, following a 5 p.m. reception in the Gibbs Room and Estes Courtyard. Proceeds benefit the Nashville Tree Foundation, an agency charged with preserving and enhancing Nashville’s urban forest by educating the public, planting trees in urban areas, identifying the oldest and largest trees in Davidson County, and designating arboretums. Click here for ticket information.

Sanders will also give a reading in Chattanooga on April 15 at 2:30 p.m. when he accepts the 2011 Cecil Woods Award for Nonfiction from the Fellowship of Southern Writers. The reading will take place during the Arts & Education Council’s biennial Conference on Southern Literature. To register for the conference, click here.