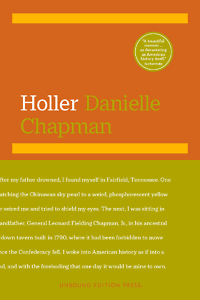

Confronting History

Poet Danielle Chapman grapples with her Southern roots

Soon after Danielle Chapman’s father was killed in a scuba diving accident while serving in the military in Okinawa, her paternal grandfather brought her and her mother to his ancestral home in Fairfield, Tennessee, where she spent much of her childhood and teen years. Living in a former tavern and antebellum farmhouse built in 1790, where she was steeped in the worldview very different from her own, she learned to love the South while questioning many of its values. That was particularly true of her grandfather, the outwardly austere former commandant of the United States Marine Corps.

In Holler: A Poet Among Patriots, Chapman, now a lecturer in poetry at Yale University, reckons with her Southern upbringing, trying to make sense of its many paradoxes. She answered questions from Chapter 16 by email.

In Holler: A Poet Among Patriots, Chapman, now a lecturer in poetry at Yale University, reckons with her Southern upbringing, trying to make sense of its many paradoxes. She answered questions from Chapter 16 by email.

Chapter 16: The subtitle of your book is “A Poet Among Patriots.” That seems to suggest you see yourself as an outsider. Can you talk a little about the subtitle?

Danielle Chapman: One definition of a poem is a “spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings” — and so being a poet is definitely somewhat at odds with the stoic stiff-upper-lip mentality of the WWII-era Marines I grew up around. However, Holler is meant to evoke not only my own crying out, but also Marines’“oorah” camaraderie and an acknowledgement of all the sufferings and war wounds they keep hidden. (As well as a Southern way of saying “hollow,” that marshy tangle between the yard and the riverbank, where I wasn’t allowed to walk alone as a kid.) So the “among” is important. The book is, in large part, an effort to recollect and resurrect family members I lost long ago. While my worldview may differ from theirs, I miss them and often wish I could be among them again.

Chapter 16: Late in the book you describe how, as a young adult, you became hungry to understand history and how doing so changed your perspective. Yet we live in a time when the teaching of history, particularly regarding race, is restricted in some conservative states, including Tennessee. Why is history, including history about race and racism, important to young people?

Chapman: Dr. Carroll Van West, who heads up the MTSU Center for Historic Preservation, puts it plainly: “History is the ultimate ‘it is what it is.’” This kind of reverence for plain fact is something I inherited from my (Southern, conservative, military) grandfather. The positive side of being skeptical about emotion is that you gravitate toward evidence. (One of Papa’s mantras was “I’m not interested in how you feel about it. What are the facts?”) We need to include race and racism in American history not only because it’s the truth, but also, complex histories are more interesting than sanitized ones. There’s nothing that can bore a child to tears more than propaganda (from either political side). Meanwhile, real history seethes with fascinating detail — some of it ugly, some of it brilliant. I think that allowing kids to discover American history, in its fullness, is an act of patriotism. Loving one’s country (or one’s family) doesn’t mean being in denial about its sins. It means reckoning with them and finding a way to move forward. To those who think that’s impossible, I’d say: Let’s try to be a bit more hopeful about who we are as Americans.

Chapter 16: A turning point came when you discovered that your grandfather had actually fought for racial and other kinds of equality in the military. Why do you think he hid that from you, particularly since you were such an inquisitive child and teenager?

Chapman: That really is such a mystery to me. I confronted him so many times about racial injustice — and his comeback to my complaints was always: Well, what are you going to DO about it? Meanwhile, he had done something big. In response to the racial unrest happening around the country in 1969, he’d issued an order that would allow Black Marines to wear their hair in a “modified Afro” and to give each other the Black Power salute as a sign of solidarity. This turned into the biggest controversy of his tenure as commandant, and I write in the book about how he received 17 boxes of hate mail — mostly from irate white people — for this decision. He didn’t ever reverse course, but it’s possible that he felt burned by all the fury and might have decided afterward that it was better to be “colorblind” than “color-conscious.” (A favorite Marine Corps motto is “All Marines are green.”) But he was pretty wise; maybe he also knew that, being an attitudinal teenager, I was unlikely to believe such a thing if I heard it from him. I wouldn’t put it past him to have foreseen that I’d eventually get curious and go dig around in his archives — and be amazed when I discovered this story myself.

Chapman: That really is such a mystery to me. I confronted him so many times about racial injustice — and his comeback to my complaints was always: Well, what are you going to DO about it? Meanwhile, he had done something big. In response to the racial unrest happening around the country in 1969, he’d issued an order that would allow Black Marines to wear their hair in a “modified Afro” and to give each other the Black Power salute as a sign of solidarity. This turned into the biggest controversy of his tenure as commandant, and I write in the book about how he received 17 boxes of hate mail — mostly from irate white people — for this decision. He didn’t ever reverse course, but it’s possible that he felt burned by all the fury and might have decided afterward that it was better to be “colorblind” than “color-conscious.” (A favorite Marine Corps motto is “All Marines are green.”) But he was pretty wise; maybe he also knew that, being an attitudinal teenager, I was unlikely to believe such a thing if I heard it from him. I wouldn’t put it past him to have foreseen that I’d eventually get curious and go dig around in his archives — and be amazed when I discovered this story myself.

Chapter 16: I understand you’ll be working with the MTSU Center for Historic Preservation to uncover the history of your family home, focusing on enslaved people there. Why is that work important to you?

Chapman: So many reasons, but the biggest one is the Singletons and McMahons, descendants of people who were once enslaved on the property. As the last chapter of Holler describes, we’ve been having reunions for 25 years, and many close relationships have formed between us in that time. Now that both my grandfather and my uncle have died, it’s my responsibility to keep the house standing (which is no easy task for a tavern built in 1790 that hasn’t been lived in year-round for over a century!). The house is of great sentimental value to me, as it’s a way of staying connected to loved ones I’ve lost. But that pales in comparison to its importance as the ancestral homeplace of the sprawling families of the Singletons and McMahons.

The collaboration with the Center for Historic Preservation at MTSU is a whole new chapter in our connection. Several Singleton descendants who live year-round in Bedford County have taken the lead as contacts for the project, and their curiosity and drive to learn about their ancestors, and the history that we share, is humbling. The work the center does is such an inspiration, partly because it’s just so down to earth. They tell detailed stories that encompass all aspects of a single place — and they find primary documents that will provide evidence for those stories (and, in some cases, refute legends that have been passed down). They’ve done extensive research on our house. But they’ve also worked with Singleton descendants to gather oral histories, and to research Black cemeteries associated with the property, with the aim of restoring them. I feel so proud of this work, and I love to imagine what my grandfather would say about it.

Chapter 16: On the surface, it would seem that memoir is a very different genre from poetry. How does your work as a poet inform your work as a prose writer? What can poetry teach prose, and vice versa?

Chapman: This memoir, though it’s pretty short, took a very long time — 12 years — to write, mostly because of the struggle over this question. I knew I had a story on my hands that was of topical interest — particularly the story of George and Robert Singleton, the interracial Civil War-era “best friends” whose tale is the subject of the last chapter of this book. I often wished that I were a journalist, and I tried for years to center the whole book around this tale. But my own psychic connection to the house where it took place was just too deep; it had formed the poet in me, and she wouldn’t let it go until I allowed the book to be her memoir.

What I mean by that is partly that it is a book driven by language and by inspiration — the flow of the sentences, the images, the outlandish characters who wouldn’t leave my memory alone. But also, it’s a book that resists the desire to tell a single narrative or reach a definitive conclusion. Instead, I hope it holds up various lives in all of their contradictions — their sins, their sufferings, their courage, their love — and creates a way for some grace to enter their stories, and my own.

Jane Marcellus is a writer whose published work includes literary nonfiction, critical analysis, and journalism. Her work has been listed as “Notable” three times in Best American Essays. She is a former professor at Middle Tennessee State University.