Capitol Crime

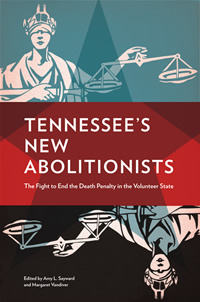

A new collection of essays denounces Tennessee’s longstanding ambivalence over the death penalty

Since the death penalty was reinstituted in 1976, Tennessee has executed only six people. That’s far less than most Southern states but far too many for the essayists in Tennessee’s New Abolitionists, which seeks to explode the myth of retributive justice and expose the state’s uneven application of capital-sentencing law. In this collection, editors Amy L. Sayward (chair and professor of history at Middle Tennessee State University) and Margaret Vandiver (professor of criminology and criminal justice at the University of Memphis) present a wide range of articles that tell the story of a passionate minority at odds with a political Goliath backed by a largely unreflective mainstream.

During the years following the Civil War, Tennessee was the only formerly Confederate state to outlaw execution. Especially in urban areas, the “Athens of the South” trumpeted a progressive attitude toward politics and social issues that disguised deep-seated prejudices and economic problems. Those issues reemerged in the wake of World War I: as resources became short, and racial and political intolerance once again dictated public policy, the death penalty was reinstated. Since then, unlike its Southern sister states, Tennessee has been remarkably ambivalent on the subject of capital punishment––a phenomenon Sayward attributes to the state’s wealth of southern Protestants who remain split between Christian progressivism and the myth of redemptive violence. In the first of its three sections, Tennessee’s New Abolitionists provides a history of the state’s anti-death penalty struggle, shedding light on the mixed sentiments that have kept Tennessee’s executions to a minimum even as capital sentencing has increased.

MTSU professor Sekou M. Franklin’s essay, “The New South’s Abolitionist Governor,” for example, tells the story of Frank G. Clement, a progressive Democrat who during the 1950s and 1960s was twice elected governor of Tennessee in spite of his outspoken opposition to the death penalty. An evangelical Christian, Clement’s willingness to mix spirituality and politics cut both ways. On the one hand, his fundamentalism and close association with the Rev. Billy Graham appealed to rural voters; on the other, his commitment to evangelical liberalism––including the commandment You shall not kill––placed him on the side of abolition.

MTSU professor Sekou M. Franklin’s essay, “The New South’s Abolitionist Governor,” for example, tells the story of Frank G. Clement, a progressive Democrat who during the 1950s and 1960s was twice elected governor of Tennessee in spite of his outspoken opposition to the death penalty. An evangelical Christian, Clement’s willingness to mix spirituality and politics cut both ways. On the one hand, his fundamentalism and close association with the Rev. Billy Graham appealed to rural voters; on the other, his commitment to evangelical liberalism––including the commandment You shall not kill––placed him on the side of abolition.

In 1972 the U.S. Supreme Court’s Furman decision ruled that capital punishment was unconstitutional. Four years later Furman was superseded by the Gregg decision, which mandated, among other things, separate guilt and sentencing phases for capital trials. With a new constitutional standard in place, the Tennessee legislature scrambled to draft a new death-penalty law––even though the state would be unwilling to carry out an execution for another twenty-three years.

The second section of Tennessee’s New Abolitionists describes the theological, legal, and journalistic responses to the state’s 1976 reinstatement of capital punishment. Of particular interest is an article by former Tennessee Supreme Court justice Penny J. White, the only Tennessee judge ever ousted on a yes/no vote. Along with the rest of the court, White had voted to overturn the death sentence of Willie Odom, who had been found guilty of raping and killing 78-year-old Mina Ethel Johnson in 1991. In “Judicial Independence and Capital Punishment in Tennessee,” White relives her decision to retry Odom––a conclusion she came to on strict constitutional grounds––and the political furor that led to her removal. For White, the real victim of the controversy is the constitutional provision for an independent judiciary, which requires judges to rule in accord with existing law or judicial precedent independent of personal opinion or political pressure.

The final section of Tennessee’s New Abolitionists is perhaps its most effective, for it gives voice to those primarily affected by Tennessee’s death-penalty statutes: the people on death row and those charged with their care and spiritual welfare. Particularly moving are the “Last Thoughts” of Sedley Alley, a Navy veteran and father of two who was executed for murder in 2006. Alley details his life on deathwatch: his final hours before being led to the execution chamber. Rather than being bitter or angry, Alley takes the opportunity to be thankful for his friends and family and to offer an indictment of the skewed system of justice that will soon take his life: “The death penalty is like killing the enemy––decades––(sic) after the battle is over, and enjoying doing it.”

Unquestionably, Tennessee’s New Abolitionists has an axe to grind. Perhaps the book would be stronger if it included at least one opposing view. Nevertheless, as even many death penalty supporters acknowledge, the state’s current statutes fail basic standards of justice. Over half the state’s death-penalty convictions are overturned on appeal, and there’s no doubt about the role that race, mental stability, and economic class plays in death penalty sentencing. Tennessee’s New Abolitionists is a reminder of how complicated are the seemingly simple issues put forth by the “eye for an eye” crowd. For that reason alone it should be required reading for all Tennesseans.

Amy L. Sayward discusses and signs Tennessee’s New Abolitionists at Davis-Kidd Booksellers in Nashville on August 26 at 7 p.m.