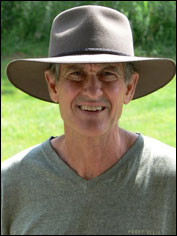

Extraordinarily Ordinary

Sam Pickering pens a delightfully meandering memoir about his angst-free boyhood

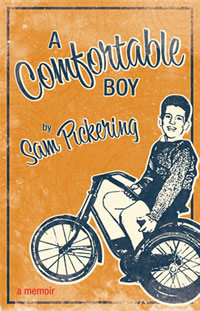

A Comfortable Boy is essayist Sam Pickering’s twenty-third book, but the message is the same one he’s been offering since he first began writing relatively late in life. For Pickering, ambition and conformity are overrated, paling in comparison to a life led not so much for purpose as for finding pleasure and passion in the most quotidian occasions.

It’s the same message, too, that has pervaded the Tennessee native’s teaching career. Pickering is a professor of English at the University of Connecticut in Storrs and is teaching this summer at the Sewanee School of Letters. Pickering made a profound impression on former student Tom Schulman, for example, a Nashville-born screenwriter who based a character in his most famous screenplay on an unconventional instructor at Montgomery Bell Academy who counseled his students to “seize the day.” Maybe you’ve heard of it: a little film called Dead Poets Society.

While the movie brought notoriety and opportunities, Pickering resisted them, instead “wandering” through life on his own terms. “I don’t consider myself ambitious,” he writes in an email to Chapter 16 as part of a virtual interview about his latest book and—his specialty—miscellany. “I just fill the bright hours with what strikes me as brightness. By turning down honors and prominent posts, I have been able to control some of the doings of my life. Never underestimate the Power of Negative Thinking. I used to say, ‘I am just a boy who can’t say yes.’ Ambition turns a person into a circus performer, leading him to twist his being out of shape in order to delight and curry the favor of others.”

Instead, the 68-year-old Pickering has made a writing career of the “familiar” essay that meanders among the ordinary, humorous, and keen observations of someone who likes to spend hours in the woods every day. (In an email, Pickering notes, “Yesterday, I walked the Perimeter Trail at Sewanee for four hours. The day before I walked for three and a half, the same for the day before that. Thoreau said he walked four hours a day. I am a three-and-a-half-hour guy.”)

Instead, the 68-year-old Pickering has made a writing career of the “familiar” essay that meanders among the ordinary, humorous, and keen observations of someone who likes to spend hours in the woods every day. (In an email, Pickering notes, “Yesterday, I walked the Perimeter Trail at Sewanee for four hours. The day before I walked for three and a half, the same for the day before that. Thoreau said he walked four hours a day. I am a three-and-a-half-hour guy.”)

Pickering’s latest book details not only an idyllic childhood in Nashville—he ends the narrative in middle school, before his time at Montgomery Bell Academy—but also a delightful collection of family history, nuggets from relatives’ attics, quite literally, which were a treasure-trove of mystery and intrigue for a curious, well-read buck from the South. In fact, “prowling” in the hot dusty rooms of the family elders was among his favorite youthful pastimes. It didn’t hurt that his parents didn’t buy a television until he was eleven, by which time he was already a bookworm, and inveterately inquisitive.

“By exploring the past of my family, I wander the present, discovering that matters that relatives thought important marked the pages of my mind,” he writes in A Comfortable Boy. “Grandmother Pickering studied small matters in hopes of discovering beauty. ‘Life,’ she said in a report to the grand chapter of the Eastern Star, ‘is made up of little things; little books so dearly read, little songs so dearly sung, and when nature made anything especially rare and beautiful, she made it little—little diamonds, little pearls, and little dew.’ I, too, have long celebrated the small and ordinary.”

When his then-two-year-old daughter Eliza woke him during the night to go to the bathroom, for example, Pickering describes what she said as he pulled up the covers: “I love you Daddy. You are the best daddy in the whole world.” What he writes in response is simple, even obvious, yet endlessly touching. “Nothing anyone has said since has meant more to me.”

Though he insists he’s not “clever” enough to have consciously framed the book this way, reading A Comfortable Boy feels a bit like making your way through a giant trunk of yellowed family papers—at times linear, as though reading two letters that lay crumbled but chronological, though other times full of the kinds of tangents and deviations such assorted remnants might necessarily dictate.

Though he insists he’s not “clever” enough to have consciously framed the book this way, reading A Comfortable Boy feels a bit like making your way through a giant trunk of yellowed family papers—at times linear, as though reading two letters that lay crumbled but chronological, though other times full of the kinds of tangents and deviations such assorted remnants might necessarily dictate.

Pickering leads the reader through his boyhood life in large part by sharing those family treasures, which include writings from his middle school days at Nashville’s Parmer School, where he was president of his eighth-grade class; a card the Good Samaritan Colored Society sent, along with flowers, to the 1919 funeral of his great grandfather, who had been a Union soldier from Ohio and later Carthage, Tennessee; Civil War-era letters from ancestors or friends of ancestors about romance and the ravages of war; even his father’s first-grade compositions. The sheer volume of Pickering’s preserved family annals is utterly worthy of envy. (He says entering his basement and attic—yes, we asked—is “impossible,” as they are littered with heirlooms.)

In the book Pickering recalls trying one time to write an essay describing an unhappy childhood. But even this essayist— who is not averse, occasionally, to supplementing his work with fictionalizations—couldn’t get beyond the first sentence. “In truth, my childhood was wondrously happy,” he writes. “No incest, alcoholism, quarrels, divorce, eating disorders, or questions of identity made my days relentlessly unforgettable. My parents and indeed my grandparents were sane, decent, and unfailingly loving. Feigning unhappiness was impossible, so I tossed my unhappy childhood into the waste can and wrote a book called Deprived of Unhappiness.”

A Comfortable Boy remains true to Pickering’s habit of self-effacement. In the introduction, he characterizes his work as “filled with little, forgettable accounts of decency and love, stories that nudge the funny bone and provoke soft smiles. Perhaps a few readers will close this book and scrolling back through their years discover the stuff of their happiness, material that will make them appreciate the present more.”

There are some obvious flaws in Pickering’s insistence on his own ordinariness and lack of ambition. Among them are an alphabet soup of degrees from academic bastions such as the University of the South, St. Catherine’s College, and Princeton University, to say nothing of his many published books and essays and the aforementioned motion picture, in which Robin Williams plays the character based on Pickering. But lack of pretension is hardly a character flaw, and Pickering more than delights in this charming, if sometimes nomadic, memoir.