Mama? She's Crazy

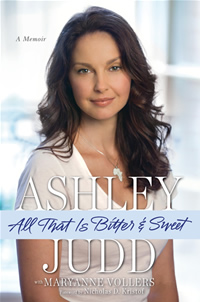

Film star Ashley Judd turns a grim upbringing––and crushing depression––into a life of service

It may appear that Ashley Judd has led a charmed life. The daughter/sister of famed country duo Naomi and Wynonna Judd, she seemed to appear out of nowhere during the mid-90s, her pixie-like presence lighting up films such as Smoke, Kiss The Girls, and 2004’s De-Lovely, for which she earned a Golden Globe nomination. Add to that her 2001 marriage to dashing Scottish race-car driver Dario Franchitti, and it looks like Ashley Judd has it all.

But there’s a dark side to Judd’s fame—and, indeed, to the seemingly wholesome Judd empire itself. Infidelities, substance abuse, sexual abuse, neglect, and high drama dominated the family’s personal and professional lives, leaving Judd to fight a lifelong battle with depression and dysfunction. By struggling with those issues, however, she discovered her true calling: social activism. Recognizing herself in the lost children of Africa and Asia, Judd has emerged as one of the most recognizable faces in the international fight against AIDS and sexual violence, and a powerful voice for gender equality. Most recently, she has also become a leading spokesperson for wildlife defense.

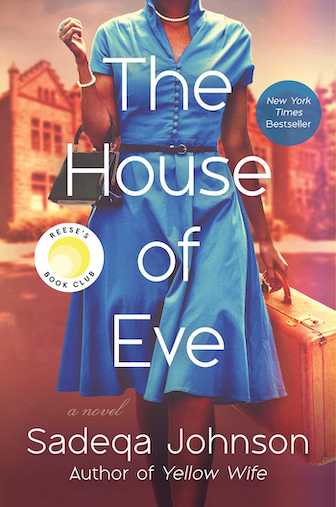

This is the stuff of Judd’s memoir, All That Is Bitter & Sweet. Written with Maryanne Vollers, who also co-wrote bestselling memoirs by Hillary Rodham Clinton and Jerri Neilsen, the book begins deep in the heart of the Congo, in a camp for the forcibly displaced. It’s a hopeless, dirty scene, and desperate children cling to Judd—not as an American movie star but as a rare source of fundamental human comfort. The scene will be repeated many times in All That Is Bitter & Sweet, as Judd transforms her gut-wrenching past into a more hopeful tomorrow for some of the world’s most disenfranchised people.

Judd was born in Southern California in 1968. Her parents, Michael and Diane Ciminella, were typical of that restless time: natives of rural Eastern Kentucky, they married young and moved West for a fresh start. Diane Ciminella (née Judd), later to be renamed Naomi, needed a fresh start: she had recently given birth to a daughter, Christine, later called Wynonna. Unbeknownst to all—except Diane, of course—Michael was not Christine’s real father. This secret came to define the relationships between the Judd women. “When I came into the world four years later,” Judd writes, “my family’s troubled and remarkable course had already been set in motion, powerfully shaped by mother’s desperate teenage lie and the incredible energy she dedicated to protecting it.”

As Judd grew up, her mother’s restlessness increased. After divorcing Ciminella, Naomi moved the family back to Kentucky. Spurred by her mother’s roiling ambition—and, apparently, no small amount of lust—the family’s frequent relocations resulted in Judd’s attending thirteen schools before reaching college. She was passed back and forth between mother, father, both sets of grandparents, and various relatives and friends, one of whom sexually abused her. By the time the family settled in a decrepit farmhouse in Franklin, Tennessee, Naomi’s dreams of stardom were in full bloom, and Ashley Judd, now in high school, was essentially an orphan.

Like a lot of young adults, Judd found salvation in college. As an above-average student at the University of Kentucky, she involved herself in all manner of progressive causes. “My sense of fairness—or more accurately, unfairness—was being keenly developed, both inside and outside the classroom, equipping me and motivating me for the life of service I now love and that gives my every day such purpose,” she writes. That passion would eventually lead Judd to complete a master’s degree in Public Administration from the John F. Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University in 2010.

Like a lot of young adults, Judd found salvation in college. As an above-average student at the University of Kentucky, she involved herself in all manner of progressive causes. “My sense of fairness—or more accurately, unfairness—was being keenly developed, both inside and outside the classroom, equipping me and motivating me for the life of service I now love and that gives my every day such purpose,” she writes. That passion would eventually lead Judd to complete a master’s degree in Public Administration from the John F. Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University in 2010.

Years earlier, after her graduation with honors from the University of Kentucky—which no one from her family attended—the pull of the theater initially kept Judd from considering a career in advocacy work. “Theater was one of my minors,” she writes, “and I had been doing what I know today as acting—living truthfully under imaginary circumstances—since the third grade.” Judd moved to Los Angeles, and soon landed a role on the hit NBC show, Sisters. Shortly thereafter, she was cast in the acclaimed indy film Ruby in Paradise, and her acting career took off.

Despite success in Hollywood, Judd found herself subject to bouts of anxiety, insomnia, lethargy, and long periods of depression—spells she refers to as “falling through the trapdoor.” She began a self-prescribed course of treatment that included yoga, keeping a journal, therapy, and prayer. Then, in 2002, with both career and emotional troubles at their zenith, Judd received a letter asking her to serve as global ambassador for YouthAIDS, an AIDS/HIV prevention program sponsored by Population Services International—one of the many non-governmental organizations with which she is currently affiliated.

As spokesperson for PSI, Judd found herself in some of the most hopeless spots on earth: the brothels of Cambodia and Thailand, and the AIDS-ridden relocation camps of sub-Saharan Africa. She felt as if she had finally found her calling, but the suffering she witnessed only made life at home more unmanageable. “I might be able to confidently lobby archconservative Senate majority leader Mitch McConnell in his chambers, but I couldn’t seem to manage the simple task of finding a comfortable chair for my writing desk,” she writes.

Meanwhile, Judd’s sister Wynonna was wrestling with her share of the family demons. In 2006, she began inpatient treatment for overeating. While visiting her sister during family week, Judd came to terms with the overarching cause of her own codependence and her inability to set appropriate boundaries in her advocacy work. She checked into the very same treatment program as Wynonna. Like the young victims of poverty Judd had vowed to help, she too was a Lost Child, to use recovery parlance. With this realization came a fresh commitment: “Having finally become an advocate for the beautiful little girl who lived inside of me and who needed a healthy adult on her side, I predicted I would now feel even better equipped to advocate on behalf of others with more usefulness, compassion, and integrity.”

Its reminiscences occasionally come off as touchy-feely and overly optimistic, but All That Is Bitter & Sweet makes no attempt to sugarcoat the horrors Judd has witnessed, both as an advocate and as a victim. Though she continues to act, Judd has thrown off many of the trappings that modern society holds dear: celebrity, fortune, and Hollywood glitz. Along the way, her suffering has become palpable, but so has her willingness to forgive the family that wronged her. Beyond talent, good looks, and a magnetic personality, an actor’s great skill is her resilience, and that’s a quality Ashley Judd apparently has in spades.