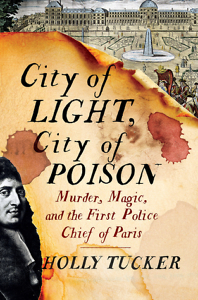

Crime Capital of the World

Book excerpt: City of Light, City of Poison: Murder, Magic, and The First Police Chief of Paris

Late seventeenth-century Paris assaulted the senses and rattled the nerves. Screams and yells echoed off the walls of narrow streets as Parisians lodged boisterous complaints against the insults of urban life: fistfights among angry neighbors, cutpurses racing from victims, chamber pots dumped out from upper floors onto passersby below. Carriage drivers swore and taunted one another as they jockeyed for command of the street. Packs of vendors shouted at the top of their lungs. Sounds of animals punctuated the cacophony: dogs barked, roosters crowed, cows lowed as they strolled with their bells clanking.

The filth of Paris attached itself to clothes, the sides of buildings, and the insides of nostrils. Several times a week, butchers, tanners, and tallow makers welcomed herds of cattle and sheep to the city’s central slaughterhouses, located near streets with names like rue Pied-de-Boeuf (Cow-Foot Street) and rue de la Triperie (Tripe-Shop Street). On Thursdays and Fridays, Parisians had no choice but to trudge through inches of congealed blood. Even on nonslaughter days, the streets were permanently rust colored from the blood that had soaked into the earth.

The filth of Paris attached itself to clothes, the sides of buildings, and the insides of nostrils. Several times a week, butchers, tanners, and tallow makers welcomed herds of cattle and sheep to the city’s central slaughterhouses, located near streets with names like rue Pied-de-Boeuf (Cow-Foot Street) and rue de la Triperie (Tripe-Shop Street). On Thursdays and Fridays, Parisians had no choice but to trudge through inches of congealed blood. Even on nonslaughter days, the streets were permanently rust colored from the blood that had soaked into the earth.

There were no sidewalks in Paris. No European city had them. In a futile response to the mud, many homeowners installed a protruding iron bar at ankle height in their home’s stone edifice, so visitors could scrape the foul muck from their shoes before entering. To avoid walking in the streets altogether, those who could afford to hire carriages increasingly did so. In the mid-seventeenth century, there were barely three hundred carriages navigating the streets. Within just a few decades, that number swelled to well over ten thousand, creating traffic jams in the narrow streets for hours at a time and, worse, a major safety hazard. As one Italian traveler wrote, “There is an infinite number of filthy carriages covered in mud, which serve to kill the living.”

Overcrowded and dirty, Paris brought even the most levelheaded of inhabitants to the brink of violence. Conflicts were frequently adjudicated by a supply of weapons—from brass knuckles and clubs to daggers and rapiers—kept close at hand. When street “justice” was dealt, it came swiftly and often to the great shock of its victim. Only steps from the king’s library on the rue Richelieu, a watchmaker encountered a former customer. Bypassing all polite greetings, the man launched into vitriolic complaints about defects in the watch he had bought a year earlier. When the watchmaker protested, his customer smashed a heavy sword into the watchmaker’s head, leaving him dead.

The new accessibility of pistols across social classes turned an already dangerous city into an even more deadly one. The product of the sixteenth-century discovery of saltpeter, guns revolutionized early European warfare overnight. By the 1640s the French had perfected flintlock-firing technology, which made guns much lighter, smaller, and less expensive to produce than traditional wheel-lock guns and rifles. Armed with pocket-size pistols under their cloaks, thieves became bolder. Parisians looking to protect their homes raced to buy handguns, making the city all the more unsafe.

The new accessibility of pistols across social classes turned an already dangerous city into an even more deadly one. The product of the sixteenth-century discovery of saltpeter, guns revolutionized early European warfare overnight. By the 1640s the French had perfected flintlock-firing technology, which made guns much lighter, smaller, and less expensive to produce than traditional wheel-lock guns and rifles. Armed with pocket-size pistols under their cloaks, thieves became bolder. Parisians looking to protect their homes raced to buy handguns, making the city all the more unsafe.

In response to the rising violence, the Crown issued an edict in 1660 calling for the ban of all weapons including—and especially— handguns, by anyone other than soldiers, police officers, judges, and noblemen. The law did not have the desired effect. Another ordinance issued six years later repeated the 1660 law nearly verbatim. It also added that all handguns needed to be conspicuous, heavy, and with barrels that were at least fifteen inches long. Any person in possession of such a weapon was required to carry a lantern or a torch as he moved through the streets at night, so both law officials and citizens could see that the person was armed. Judging from the violence that filled the city after dark, few followed this mandate either.

By night Paris became frighteningly claustrophobic. At sunset, soldiers pulled shut the massive gates of the city’s ramparts and lowered the barricades behind them. But the gates did little to protect those locked in with their fellow citizens. Nighttime revelers made their way across a city plunged into inky shadows, with only the faint glow of candlelight peeking through a drape or shutter illuminating a small stretch of street. Homeowners and shopkeepers battened down their homes and stores, pulling shut windows and doors for the night like sailors preparing for a storm. Here the weapons came in handy. As one Mademoiselle Surqualin said nonchalantly to the police after killing an intruder, she always kept a knife at her bedside precisely for that task.

Despite its dangers, a vibrant city still beckoned. Some heeded the siren call of the city’s drinking holes. Most streets boasted at least two or three taverns of varying repute. They advertised themselves with colorful names like the Cradle, the Lion’s Ditch, or the Fat Grape—and they attracted neighborhood locals eager to eat, drink, or pick a fight.

Paris did not have a centralized police force until the late seventeenth century. Instead policing responsibility for the city lay in the hands of just forty-eight commissioners—fewer than one commissioner for every fifteen thousand Parisians. In theory each commissioner maintained order in the quarter in which he lived, but the commissioners learned quickly that fighting crime did not pay. What did pay was the mountain of bureaucratic and legal tasks required after crimes were committed. A visit to a commissioner’s home, which served as his office, was the first stop in the long, and often expensive, process toward finding justice. The commissioner scanned each person who walked through the door for signs of his or her ability to pay. One commissioner, Nicolas de Vendosme, certainly made such an assessment when a local laborer came to lodge a complaint on behalf of his two sons, who worked as apprentices to a woodcarver. The agitated father declared that the woodcarver had pushed his sons into the muddy street and swung a mallet at one of them. It was sheer luck, the father explained, that the woodcarver did not break his son’s leg.

Vendosme explained that a simple complaint against the woodcarver would set the father back fifteen sols, nearly threequarters of a day’s pay. For this the woodcarver would receive formal notification that his actions were not acceptable. If the father wished to pursue the matter in court, there would be additional fees. To begin with, paper was not free. It cost well over one sol per page, and they would need plenty of it for letters and court filings. Witnesses also expected compensation for their testimony. Then there were the clerks who required payment when they filed the complaint with the court. All this would be in addition to the commissioner’s own honorarium, which would be determined by the complexity of the case. In all, the father would be facing at least three livres, the equivalent of three full days of the workman’s wages, to pursue litigation against the woodcarver. Still, this was reasonable in comparison to the seven livres in fees that the director of a royal textile factory paid, or the ten livres that a duchess paid for similar services. When it came to seventeenth-century justice, the more one was thought able to pay, the more one usually did.

On the Left Bank of the Seine sat the castle-like Châtelet compound, which housed courtrooms as well as a prison where convicted prisoners languished following judgment. Châtelet was divided into two bureaucratic fiefdoms. One was the dominion of d’Aubray, the civil lieutenant, who served as the overall head of Châtelet. He decided disputes among individuals and groups that had implications for the public good of the city. The other was that of the criminal lieutenant, Jacques Tardieu, who had jurisdiction over most crimes committed in Paris. Like the commissioners, the lieutenants (and their staffs) were paid by the plaintiff for their efforts. Determining the jurisdiction of a case—especially high-profile ones that involved the wealthy— brought out bitter infighting. During much of the seventeenth century the legal system at Châtelet ground to a halt as the magistrates battled, often for months on end, for the right to hear certain cases.

“Day and night they kill here, we have arrived at the dregs of all centuries,” wrote Guy Patin, a doctor at the Paris Faculty of Medicine. As if things could not be any worse, the city reached its boiling point on one hot August day in 1665, when the criminal lieutenant himself was murdered in broad daylight.

René and François Touchet spent weeks spying on the home belonging to Criminal Lieutenant Jacques Tardieu, logging the comings and goings from the Left Bank household. Tardieu’s home was a classic example of the type of luxurious hôtels particuliers (city estates) that only the most affluent Parisians could afford. A tall, imposing wall separated the Tardieu family from the filth and noise of the streets surrounding it. A pair of twenty-foot-high wooden doors opened into a large courtyard, providing yet another buffer from the violent world outside.

With each passing day the Touchet brothers became more convinced that a bounty of riches lay behind the high walls. The seventy-two-year-old Tardieu attended mass regularly at Notre-Dame, a short carriage ride away from his home on the quai des Orfèvres. René and François, both in their early twenties, lay in wait one Sunday morning until the large wooden doors of the compound opened to release several carriages and a stream of servants on foot. Believing the house to be empty, the brothers scaled the wall, entered the home through an open window, and began ransacking it for jewels, money, and other precious items.

They did not realize that the elderly Tardieu had chosen to stay at home that day. The thought of joining the crowds to celebrate the Feast of Saint Bartholomew was too exhausting. Instead he and his wife sent the other members of the family off, preferring to remain at home on their own.

A frightening scream pierced Tardieu’s peaceful morning. It was the cry of his wife in an adjoining room. He scrambled from his bed as fast as his aging body allowed and shuffled down the long corridor in search of her. Moments later Tardieu heard a sickening series of sounds: the cocking of a pistol trigger, the earsplitting explosion of a bullet, followed by a dull thud. When he finally reached his wife’s room, he saw her sprawled on the floor, blood pooling around her lifeless body.

With a strength that belied his age, Tardieu lunged at the thieves, battling the Touchet brothers for the gun. One of the brothers dropped the weapon and kicked it swiftly across the room. As Tardieu crouched to retrieve it, the second brother reached underneath his belt and removed a dagger. With four strokes to the neck, Tardieu crumpled to the floor.

Servants discovered the couple’s corpses when they returned from church. Shocked, they ran into the streets screaming. The local guardsmen came and, after searching the home, they found the younger of the two brothers crouching on the roof. The elder, hiding in the cellar and covered in blood, eventually surrendered.

The brothers were charged with murder and sentenced to death. In a public spectacle not far from Tardieu’s courtrooms, criminals were executed as Parisians crowded into the square to watch.

Tardieu’s murder stunned the city’s nobility. If even the criminal lieutenant, the man responsible for sentencing violent criminals, was not safe in Paris, then who was? The answer arrived the following year when Tardieu’s counterpart and rival, Civil Lieutenant François Dreux d’Aubray, was also murdered. This time death came not by a gun or a dagger, but by poison.

Excerpted from City of Light, City of Poison: Murder, Magic, and the First Police Chief of Paris by Holly Tucker. Copyright © 2017 by Holly Tucker. With permission of the publisher, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. All rights reserved. Holly Tucker is the author of Blood Work: A Tale of Medicine and Murder in the Scientific Revolution, which was a Los Angeles Times Book Prize finalist. She lives in Nashville, Tennessee, and Aix-en-Provence, France.

Excerpted from City of Light, City of Poison: Murder, Magic, and the First Police Chief of Paris by Holly Tucker. Copyright © 2017 by Holly Tucker. With permission of the publisher, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. All rights reserved. Holly Tucker is the author of Blood Work: A Tale of Medicine and Murder in the Scientific Revolution, which was a Los Angeles Times Book Prize finalist. She lives in Nashville, Tennessee, and Aix-en-Provence, France.